Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 154, Number 51: Clean Fuel Regulations

December 19, 2020

Statutory authorities

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Environmental Violations Administrative Monetary Penalties Act

Sponsoring department

Department of the Environment

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primary contributors to climate change. The largest sources of GHG emissions in Canada are from the extraction, processing and combustion of fossil fuels. In order to exceed Canada’s current GHG emission reduction target under the Paris Agreement, and achieve the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, a number of GHG emission reduction measures have been implemented. While these actions are bringing Canada closer to meeting its climate goals, further action is required.

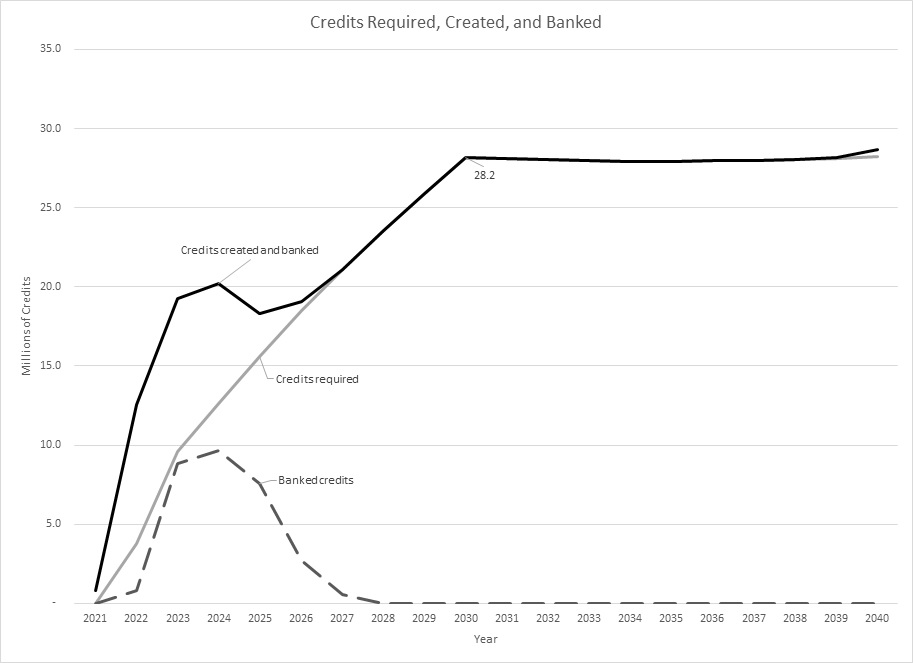

Description: The proposed Clean Fuel Regulations (the proposed Regulations) would require liquid fossil fuel primary suppliers (i.e. producers and importers) to reduce the carbon intensity (CI) of the liquid fossil fuels they produce in and import into Canada from 2016 CI levels by 2.4 gCO2e/MJ in 2022, increasing to 12 gCO2e/MJ in 2030. The proposed Regulations would also establish a credit market whereby the annual CI reduction requirement could be met via three main categories of credit-creating actions: (1) actions that reduce the CI of the fossil fuel throughout its lifecycle, (2) supplying low-carbon fuels, and (3) specified end-use fuel switching in transportation. Parties that are not fossil fuel primary suppliers would be able to participate in the credit market as voluntary credit creators by completing certain actions (e.g. low-carbon fuel producers and importers). In addition, the proposed Regulations would retain the minimum volumetric requirements (at least 5% low CI fuel content in gasoline and 2% low CI fuel content in diesel fuel and light fuel oil) currently set out in the federal Renewable Fuels Regulations (RFR). The RFR would be repealed.

Regulatory development: The annual CI reduction requirements have been informed by extensive consultation with industry stakeholders and associations (including the oil and gas sector, low-carbon energy sectors, and industry sectors that use liquid fuels), environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), representatives from provincial and territorial governments, associations representing Indigenous Peoples, administrators of similar regulations in other jurisdictions, and academics. ENGOs and stakeholders in the low carbon energy sectors support the proposed Regulations while some provincial governments and some stakeholders in the oil and gas sector have raised concerns about the costs of compliance. Since the proposed Regulations were first proposed in a discussion paper in February 2017, the Department has made a number of changes to the design of the proposed Regulations in response to feedback received.

The proposed Regulations are intended to be a flexible, performance-based policy tool that reduces the CI of liquid fossil fuels supplied in Canada. Therefore, the proposed Regulations incorporate, but also improve upon the federal RFR. The proposed Regulations would also be complementary to carbon pricing as they would provide an additional incentive to reduce GHG emissions by reducing the CI of liquid fuels, which are primarily used in the transportation sector, a major source of GHG emissions in Canada.

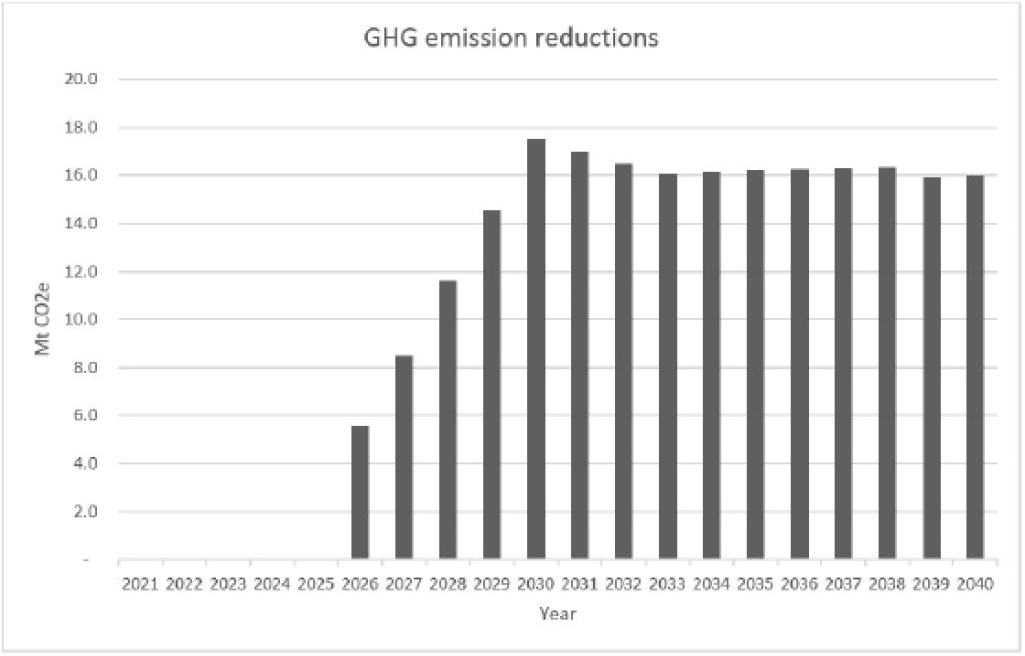

Cost-benefit statement: Between 2021 and 2040, the cumulative GHG emission reductions attributable to the proposed Regulations are estimated to range from 173 to 254 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2e), with a central estimate of approximately 221 Mt. To achieve these GHG emission reductions, the modelling conducted for this analysis estimates that the proposed Regulations could result in societal costs that range from $14.1 to $26.7 billion, with a central estimate of $20.6 billion. Therefore, the GHG emission reductions would be achieved at an estimated societal cost per tonne between $64 to $128, with a central estimate of $94. To evaluate the results, a break-even analysis was conducted that compares the societal cost per tonne of the proposed Regulations to the Departmental value of the social cost of carbon (SCC) published in 2016, and to more recently published estimates of the SCC value found in the academic literature. Given that the updated estimates of the SCC exceed the estimated societal cost per tonne of the proposed Regulations, the Department concludes that it is plausible that the monetized benefits of the proposed Regulations would exceed its costs.

The proposed Regulations would increase production costs for primary suppliers, which would increase prices for liquid fuel consumers (i.e. households and industry users). In addition, credit revenues would decrease the costs of production for low-carbon energy suppliers, which would make low carbon energy sources (e.g. biofuel and electricity) relatively less expensive in comparison. These price effects would lead to decreased end-use demand for fossil fuels and increased end-use demand for lower carbon energy sources, thereby reducing national GHG emissions. To evaluate to the direct impact of the proposed Regulations as well as the effect of relative price changes on Canadian economic activity and GHG emissions, a macroeconomic analysis was completed. When these effects are taken into account, it is estimated that the proposed Regulations would result in an overall GDP decrease of up to $6.4 billion (or up to 0.2% of total GDP) while reducing up to 20.6 Mt of GHG emissions in 2030, using an upper bound scenario where all credits are sold at the marginal cost per credit.

The proposed Regulations would work in combination with other federal, provincial, and territorial climate change policies to create an incentive for firms to invest in innovative technologies and fuels by setting long-term, predictable and stringent targets. The broad range of compliance strategies allowed under the proposed Regulations would also allow fossil fuel suppliers the flexibility to choose the lowest-cost compliance actions available. If the proposed Regulations induce more long-term innovation and economies of scale than projected in the estimates presented in this analysis, then the proposed Regulations could result in lower costs and greater benefits, particularly over a longer time frame.

One-for-one rule: The proposed Regulations would result in annualized net administrative cost increases of about $350,100 for fossil fuel producers and importers. Annualized administrative cost savings for renewable fuel producers and importers are estimated at $55,200. Overall, the total net annualized administrative cost increases are estimated at $294,900 for all stakeholders. The proposed Regulations would be considered an “IN” under the Government of Canada’s one-for-one rule.

Small business lens: The small business lens does not apply to the proposed Regulations as no mandatory participants are considered small businesses.

Issues

Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primary contributors to climate change. The largest sources of GHG emissions in Canada are from the extraction, processing and combustion of fossil fuels. GHG emissions from the oil and gas and transportation sectors account for 26% and 25% of total GHG emissions in Canada respectively.footnote 1 In order to exceed Canada’s current GHG emission reduction target to reduce emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 under the Paris Agreement, and achieve the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, a number of GHG emission reduction measures have been implemented.footnote 2 However, further action is required to meet Canada’s GHG emission reduction targets. In particular, without additional action, it is expected that emissions from Canada’s transportation and oil and gas sectors would continue to increase year-over-year.

Background

Global warming is projected to lead to changes in average climate conditions and extreme weather events. The impacts of climate change are expected to worsen as the global average surface temperature becomes warmer. Climate change impacts are of major concern for society: changes in temperature and precipitation can impact natural habitats, agriculture and food supplies, and rising sea levels can threaten coastal communities.footnote 3

The Government of Canada has committed to taking action on climate change. At the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conference in December 2015, the international community, including Canada, adopted the Paris Agreement, an accord intended to reduce global GHG emissions to limit the rise in global average temperature to less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to aim to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C. As part of its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) commitment under the Paris Agreement, Canada pledged to reduce national GHG emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.footnote 4

On December 9, 2016, Prime Minister Trudeau, along with most first ministers of Canada, agreed to the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (PCF). The PCF was developed to establish a path forward to meet Canada’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.footnote 5 November 25, 2016, as part of the PCF, the Government of Canada announced its plan to develop a Clean Fuel Standard (CFS) to reduce Canada’s GHGs by 30 Mt annually by 2030 on a lifecycle basis for fuels used in Canada.footnote 6 Since announcing the policy in late 2016, the Department of the Environment and Climate Change Canada (the Department) has engaged broadly with stakeholders on the design of the CFS and a number of formal consultation documents were released including

- a discussion paper published in February 2017, which laid out different approaches from different jurisdictions, and posed technical questions related to the potential applicability of various elements;

- a Regulatory Design Paper published in December 2018, which outlined the main design elements and approach of the CFS for liquids;

- the Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) Framework published in February 2019, which outlined the methodology for the CBA; and

- a Proposed Regulatory Approach published in June 2019, which updated and expanded on the December 2018 Regulatory Design Paper.footnote 7

On December 13, 2019, the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change (the Minister) received a mandate letter from Prime Minister Trudeau to implement a whole-of-government plan for climate action, a cleaner environment and a sustainable economy. This included implementing the PCF, while strengthening existing and introducing new GHG reducing measures to exceed Canada’s current 2030 emission reduction goal and begin work so that Canada can achieve the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Petroleum fuels and petroleum alternatives produce different quantities of GHG emissions when the full lifecycle of the fuel is considered, depending on the process used to produce the fuel, the actual composition of the fuel, and the way the fuel is used. The lifecycle of fuel accounts for all emissions connected to the extraction, production, transportation and combustion of a given fuel. Lifecycle-based fuel standards (such as the CFS) are based on lifecycle analysis (LCA) and require lifecycle carbon intensity (CI) calculations, based on the quantity of CO2 equivalent emissions per unit of energy produced (i.e. gCO2e/MJ) to assess the different GHG reduction values of fuels.

Generally speaking, CI standards or requirements are designed by assessing the CI values for each fuel using an LCA approach and comparing them to a required CI value that declines each year. Low carbon fuels that have CI values below the required CI value can generate credits, while fuels with CI values above the required CI value generate deficits. Credits and deficits are denominated in metric tonnes of lifecycle GHG emissions. Providers of fuels (the regulated parties) must demonstrate that the total mix of fuels they supply for use in the regulated jurisdiction (national or regional) meets the CI standards for each compliance period (usually a year). Regulated entities meet their compliance obligation by ensuring that the number of credits it earns or otherwise acquires from another party is equal to, or greater than, the deficits it has incurred.

British Columbia and California have implemented standards to lower the CI of fuels (called low-carbon fuel standards or clean fuel standards). Under these standards, requirements are set to reduce the lifecycle GHG emissions intensity of the fuels supplied in a given year by a certain percentage relative to a stipulated baseline year (e.g. 10% by 2020 from a 2010 baseline CI level).footnote 8 The sections below describe relevant fuel CI requirements that currently exist in Canada, the United States, and the European Union (EU).

Renewable fuel requirements — Canada

The federal Renewable Fuels Regulations (RFR) were established in August 2010. They require petroleum fuel producers and importers to have an average renewable content of at least 5% based on their volume of gasoline, and an average renewable content of at least 2% based on their volume of diesel fuel and heating distillate oil.footnote 9 The purpose of the RFR is to reduce overall GHG emissions from gasoline and diesel fuel, which is primarily used in transportation. There are exemptions for specialty fuels (e.g. those used in aircraft, competition vehicles, military combat equipment), for fuel used in northern regions, for export, for space heating purposes, and for the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Unlike the proposed Regulations, the RFR does not require reductions in GHG emissions on a lifecycle basis, nor do they contain safeguards to ensure that biofuel production does not adversely affect biodiversity (direct land use change).

Five provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario) already have renewable fuel requirements equal to or higher than the current federal requirements set in the RFR. Most of these provinces, along with Quebec, have established renewable fuel industries. Some jurisdictions (e.g. Alberta, Ontario) also require that the renewable fuels utilized meet a specific GHG performance standard.

Renewable fuel requirements — United States

Established in December 2005, the United States Renewable Fuel Standard (U.S. RFS) requires increasing annual volumes of renewable fuels to be blended into fossil fuels.footnote 10 The U.S. RFS differentiates renewable fuels based on their lifecycle GHG emission reductions, including emissions from indirect land use change. The indirect land use change impacts of biofuels relate to the consequence of releasing more carbon emissions due to land use changes induced by the expansion of croplands for biofuel production in response to the increased demand for biofuels. The annual volumetric requirements are set out for four categories of renewable fuels. The categories are designed to increase the use of renewable fuels with lower GHG lifecycle carbon intensities. Each category must meet a certain GHG reduction threshold (20% for conventional or first-generation renewable fuels, 50% for advanced biofuels, 50% for biomass-based diesel, and 60% for cellulosic biofuel). Fuels with a higher GHG reduction threshold (e.g. cellulosic ethanol) can also be used to help meet the volumetric requirements. In addition to the annual volumetric requirements for a lower GHG reduction threshold (e.g. conventional renewable fuels), the U.S. RFS requires the creation of credits, representing volumes of renewable fuels, and has a credit trading system. Currently, the RFS requires conventional renewable fuel to comprise 11% of transportation fuel, 3% of advanced biofuel, 2% of biomass-based diesel and less than 1% of cellulosic biofuel.footnote 11

Seven states also have renewable fuel requirements: Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington.

Fuel CI requirements — British Columbia, California, Oregon and the EU

In January 2010, British Columbia’s Renewable and Low Carbon Fuel Requirements Regulation (RLCFRR) came into effect. Under the RLCFRR, the RLCFRR requires reductions in the lifecycle CI of transportation fuels supplied in a given year. In addition, at least 5% of gasoline and 4% of diesel by volume must contain renewable fuel.footnote 12 Initially, fuel suppliers were required to progressively decrease the average CI of their fuels to achieve a 9% reduction in 2020 from a 2010 CI baseline.footnote 13 In December 2018, British Columbia’s Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources (the Ministry) announced in their CleanBC Plan an increase of the CI target to 20% by 2030 relative to 2010 CI levels.footnote 14 In July 2020, these amendments to the RLCFRR came into effect.footnote 13 To date, British Columbia is the only province with a low carbon fuel standard.

The RLCFRR applies to all fuels used for transportation in British Columbia with the exception of fuel used by aircraft or for military operations. British Columbia’s requirement does not differentiate between crude oil types. Fuel suppliers can comply with the RLCFRR by reducing the overall CI of the fuels they supply, acquiring credits from other fuel suppliers, or by entering into an agreement with the province. Under these agreements, fuel suppliers are able to generate credits based on actions (projects) that reduce GHG emissions through using low-carbon fuels sooner than would have otherwise occurred without the agreed-upon action. Examples of projects supported under credit creating agreements include installing and operating new pumps that supply finished gasoline with at least 15% ethanol or finished diesel with at least 10% biodiesel or 50% hydrogenation-derived renewable diesel.

Adopted in April 2010, California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard initially required fuel suppliers to reduce the CI of transportation fuels by 10% by 2020, from a 2010 baseline.footnote 15 California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard was readopted in November 2015 to correct for legal deficiencies found in the initial fuel standard while also increasing the stringency of the CI reduction requirement to help meet its original target.footnote 16 In July 2020, the California Air Resource Board approved amendments to the regulation, which require fuel suppliers to reduce the CI of transportation fuels they supply by at least 20% by 2030, from a 2010 baseline. It also added new crediting opportunities to promote zero emission vehicle adoption, alternative jet fuel, carbon capture and sequestration, and advanced technologies to achieve deep decarbonization in the transportation sector.

Oregon’s Clean Fuels Program took effect in 2016 and requires a reduction in the annual average CI of Oregon’s transportation fuels (gasoline and diesel) by 10% from the 2015 level by 2025.footnote 17 It prescribes declining maximum CI limits, for each year.

The EU also has a similar policy in place. Established in April 2009, the Fuel Quality Directive requires fuel suppliers to reduce lifecycle GHG emissions from fuels by 10% by 2020.footnote 18 The Fuel Quality Directive works in tandem with the EU Renewable Energy Directive, which stipulates that the share of biofuels in the transportation sector should be 10% (by energy content) for each member country by 2020.footnote 19

Objective

The proposed Regulations intend to reduce GHG emissions by reducing the lifecycle CI of liquid fossil fuels used in Canada. To achieve this, the proposed Regulations would incentivize low carbon fuel uptake, end-use fuel switching in transportation, and process improvements in the oil and gas sector. The proposed Regulations aim to reduce the CI of liquid fossil fuels by 12 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule (gCO2e/MJ) by 2030, which represents a decrease of approximately 13% in CI below 2016 levels. The proposed Regulations would work in conjunction with other federal, provincial and territorial policies to help exceed Canada’s current 2030 GHG emission reduction target under the Paris Agreement, and put Canada on a path towards the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. In doing so, the proposed Regulations would encourage innovation and growth by increasing incentives for the development and adoption of clean fuels and energy efficient technologies and processes.

Description

Subsection 139(1) of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) states that no person shall produce, import or sell a fuel that does not meet the prescribed requirements. The proposed Regulations, which would be made under subsection 140(1) and, for the compliance credits regime, under section 326 of the CEPA, would implement this prohibition.

Under the proposed Regulations, producers and importers of liquid fossil fuels, called primary suppliers, would have to reduce the lifecycle CI of the liquid fossil fuels they produce or import in Canada. Most primary suppliers are corporations that own refineries and upgraders. The proposed Regulations would establish annual lifecycle CI limits per type of liquid fossil fuel, expressed in grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule (gCO2e/MJ). The liquid fossil fuels that would be subject to the annual CI reduction requirement are gasoline, diesel, kerosene and light and heavy fuel oils. This obligation would be placed on primary suppliers who domestically produce or import at least 400 cubic metres (m3) of liquid fossil fuel for use in Canada. Non-fossil fuels would not have a CI reduction requirement.

The annual lifecycle CI reductions requirements for liquid fossil fuels would come into force in December 2022 starting at a 2.4 gCO2e/MJ reduction in CI and increasing to 12 gCO2e/MJ by 2030 at a rate of 1.2 gCO2e/MJ per year. Reduction requirements for the years after 2030 would be held constant at 12 gCO2e/MJ, subject to a review of the regulations and future amendments.

A primary supplier’s annual reduction requirement would be expressed in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) and would be calculated on a company-wide basis, summing up the reduction requirements per liquid fossil fuel type for each of a company’s production facilities and for their total imports, based on the energy content of fossil fuels. The proposed Regulations would also incorporate the minimum volumetric requirements that are currently set out in the federal RFR, requiring a minimum 5% low-carbon-intensity fuel content in gasoline and 2% low-carbon-intensity fuel content in diesel fuel and light fuel oil.

The proposed Regulations would set out the baseline CI values for each fossil fuel type (e.g. gasoline or heavy fuel oil) produced in and imported for use in Canada. These values are Canadian average lifecycle CI values, calculated from the Department’s Fuel Lifecycle Assessment Model. This means that every type of fossil fuel is assigned the same national average value. GHG emissions from all stages in a fuel’s lifecycle are included in the determination of the baseline CI values. The proposed Regulations would also set out the annual CI limits for each fossil fuel type. The annual CI reduction requirements (e.g. 12 gCO2e/MJ in 2030) that primary suppliers would have to meet for the fuels they supply to Canada is the difference between the baseline CI value and the CI limit for that fossil fuel type. All fossil fuel types have the same annual CI reduction requirement. The proposed Regulations would not differentiate fossil fuels based on crude oil type, or whether the crude oil is produced domestically or imported into Canada.

The proposed Regulations would include a limited number of exemptions from the annual compliance obligation. Reduction requirements would not apply to aviation fuel, fossil fuel exported from Canada, fossil fuel used in scientific research, and fossil fuel sold or delivered for use in competition vehicles. In addition, certain volumes would be excluded from the primary supplier’s pool. These include liquid fossil fuels sold or delivered for a use other than combustion, produced in a facility for use in that facility (other than in mobile equipment), sold or delivered for use in a marine vessel with an international port destination, and sold or delivered for non-industrial use in remote communities. Remote community is defined as a geographic area that is not serviced by an electrical distribution network that is under the jurisdiction of the North American Electric Reliability Corporation or by a natural gas distribution system.

The proposed Regulations would establish a credit market, where each credit would represent a lifecycle emission reduction of one tonne of CO2e. For each compliance period (typically a calendar year), a primary supplier would demonstrate compliance with their reduction requirement by creating credits or acquiring credits from other creators, and then using the required number of credits for compliance. Once a credit is used for compliance it is cancelled and can no longer be used.

To meet the minimum volumetric requirements incorporated from the RFR, each primary supplier would be required to demonstrate for each compliance period that, of the total number of compliance credits it retires for compliance, a minimum (equivalent to 5% of its gasoline pool and 2% of its diesel and light fuel oil pool) is from low-CI fuels. These compliance credits are part of the total credits used to meet reduction requirements, but the same compliance credit cannot be used to meet the 2% and 5% requirements respectively. Primary suppliers who have surplus compliance units under the RFR would be able to convert these units into credits under the proposed Regulations after the end of the final compliance period of the RFR.

Parties that are not fossil fuel primary suppliers would be able to participate in the credit market as voluntary credit creators. In addition to the primary suppliers that would be subject to the CI reduction requirements in the proposed Regulations, other possible credit creators would include low carbon fuel producers and importers (e.g. a biofuel producer), electric vehicle charging site hosts, network operators, fuelling station owners or operators, as well as parties upstream or downstream of a refinery (e.g. an oil sands operator).

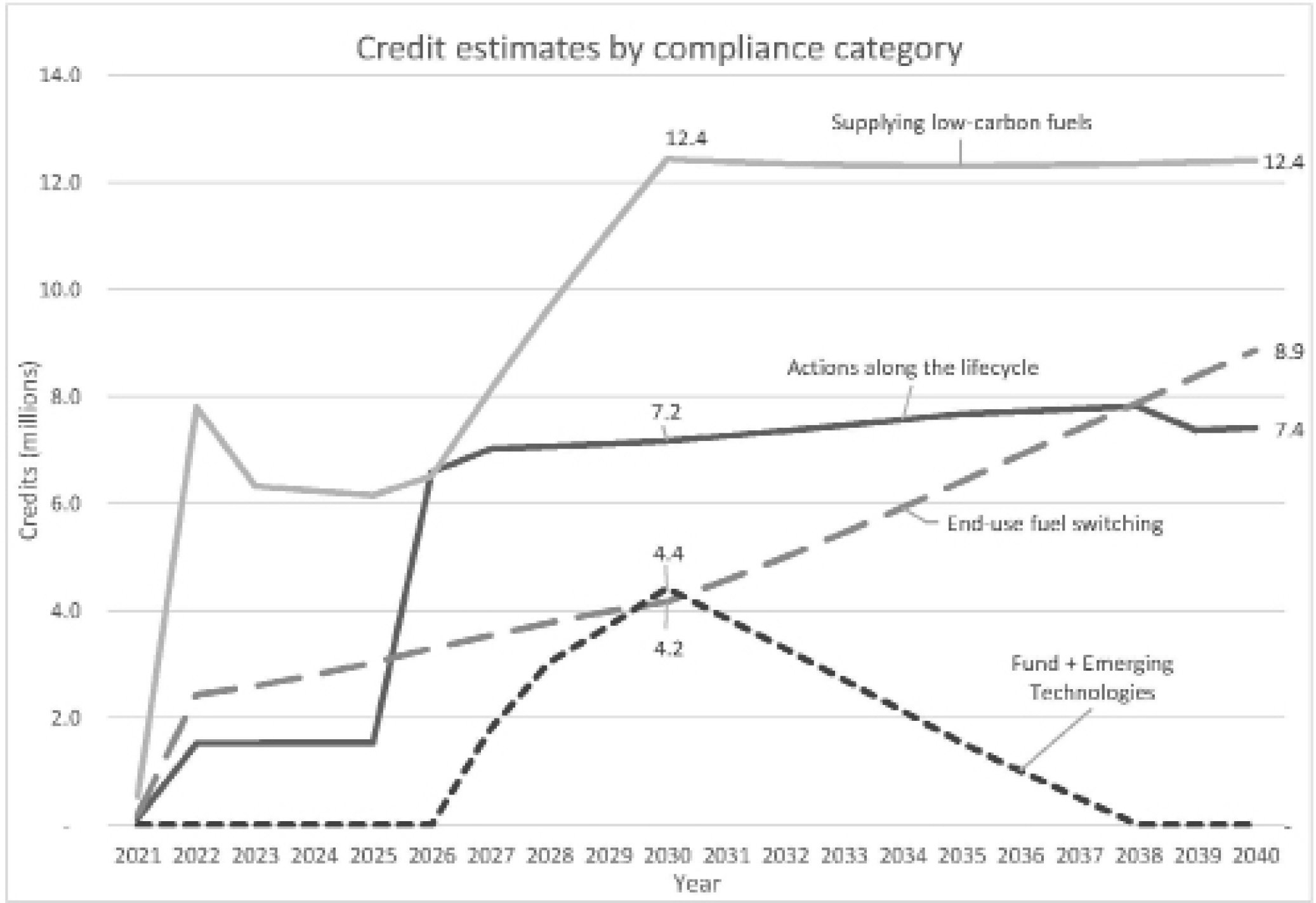

Credits may be created by primary suppliers or voluntary credit creators who take one of the following actions:

- Compliance Category 1: actions throughout the lifecycle of a fossil fuel that reduce its CI (such as carbon capture and storage) through GHG emission reduction projects;

- Compliance Category 2: supplying low carbon intensity fuels (such as ethanol); or

- Compliance Category 3: end-use fuel switching in transportation (when an end user of fuel changes or retrofits their combustion devices to be powered by another fuel or energy source, such as electricity in transportation).

Primary suppliers would also be able to use compliance credits created following credit creation rules related to reducing the CI of gaseous or solid fuels for up to 10% of their liquid class reduction requirement. The crediting opportunities for gaseous and solid fuels would include projects that reduce emissions in the lifecycle of solid and gaseous fuels, and the production or importation of low CI gaseous fuels including renewable natural gas, biogas, hydrogen and renewable propane.

Compliance Category 1 recognizes actions that reduce a fossil fuel’s CI through GHG emission reduction projects to create credits. Credits can be created as of the date of registration of the final Regulations. Projects can include an aggregation of reductions from multiple sources or facilities, and no minimum emissions reduction threshold is set. The number of credits created would be determined by a quantification method, which specifies the eligibility criteria for the project as well as the approach for quantification. Quantification methods would be maintained outside of the proposed Regulations and developed by a team of technical experts, including departmental representatives, and reviewed by a broader consultative committee that includes stakeholders in industry, academia, and other technical experts.

The Department would develop quantification methods for various project types, starting with the following list:

- carbon capture and storage;

- low-carbon intensity electricity integration;

- enhanced oil recovery; and

- co-processing of biocrudes in refineries and upgraders.

This work would take into consideration existing emission reduction accounting methodologies or offset protocols in other jurisdictions. The Department would develop a generic quantification method for projects for which there is no applicable quantification method. Projects such as energy efficiency, cogeneration, electrification and methane reductions could be recognized under the generic quantification method provided they meet the eligibility criteria.

To be able to create credits under the proposed Regulations, a project would have to generate emission reductions that are real and incremental (i.e. additional) to a defined base case. The base case would be defined in the quantification method for each project type. The generic quantification method will predefine the base case for some foreseen project types or provide guidance on how to determine the baseline for other project types. A primary supplier may use credits created under the generic quantification method in order to satisfy up to 10% of its total liquid reduction requirement annually.

For all quantification methods other than the generic method, additionality would be assessed during the development of the quantification method at the project type level and would take into account many factors, including whether an action is required by another Canadian law or regulation, technological and financial barriers, and the market penetration rate of the technology or practice. Quantification methods would be periodically reviewed for additionality and maintained, modified or withdrawn as business as usual activities evolve. For the generic quantification method, separate and more streamlined additionality criteria would be developed and assessed at the project level.

Eligible projects must be conducted in Canada. They must also reduce the CI of a fossil fuel at any point along its lifecycle, achieve incremental GHG emission reductions, and must have begun to reduce, sequester, or use CO2e emissions on or after July 1, 2017. Project proponents would first apply to the Department to have a project recognized for credit creation and would submit a validation report. Each year, they would report information specified in the appropriate quantification method that is accompanied by a third-party verification report and a verification opinion. Credits would be created for 10 years for emission reduction projects, except for carbon capture and storage projects, which would create credits annually for a minimum of 20 years. In addition, projects may be renewed a single time for an additional 5 years after the initial crediting period, provided an applicable quantification method still exists at the time of renewal.

Compliance Category 2 encompasses credits that would be created under the proposed Regulations for low CI fuels produced or imported in Canada. Low CI fuels are fuels, other than the fossil fuels subject to the CI reduction requirements, that have a CI equal to or less than 90% of the credit reference CI value for the fuel. Most low CI fuels available on the market are forms of biofuels, such as ethanol. Other low CI fuels include synthetic fuels, such as those made from the CO2 captured from the atmosphere as a result of direct air capture or syngas generated from any biomass resource that could also be employed to make new low CI fuel products under a circular economy approach.

All low CI fuels supplied to the Canadian market, including fuels used to comply with existing federal and provincial renewable fuel regulatory requirements and British Columbia’s RLCFRR, would be able to create credits under the proposed Regulations. Credits may be created for liquid and gaseous low CI fuels as of the date of registration of the final Regulations. Credits for low CI fuels would be created based on the amount of low-carbon fuel they supply to the Canadian market annually (in MJ), the difference between the lifecycle CI of the low CI fuel, and the credit reference CI value for the fuel. In order to create credits, a low CI fuel producer or foreign supplier would be required to obtain an approved CI value for each low CI fuel that they produce or import. The proposed Regulations would require the use of either the Fuel Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) Model to calculate facility-specific CI values using facility-specific data, or the use of disaggregated default values available in the proposed Regulations.

A Fuel LCA Model is being developed by the Department to support the development and implementation of the proposed Regulations. Fuel producers and foreign suppliers would be able to use the model to determine facility-specific CI values once they have 24 months of operating data. They could use a provisional CI value using the model with only 3 months of data, until 24 months of data is available. Facilities with less than 3 months of operating data for a low CI fuel would need to use prescribed disaggregated default values. Fuel producers would be required to submit an application to the Minister for approval of each fuel’s CI, as well as submit an annual CI report that demonstrates that the CI has not increased above 0.5 gCO2e/MJ of the approved CI. The approved CI values would no longer be valid if there are changes at the facility and the approved CI is no longer representative of the production processes for the low CI fuel, or if changes occur that increase the CI of the fuel by more than 0.5 gCO2e/MJ above. A minimum threshold of an improvement of 1.0 gCO2e/MJ or 5% difference between the approved value and the proposed new value, whichever is greater, would be required in order to submit a request for a new CI value.

As noted above, the proposed Regulations would allow the creation of credits from the production of low CI fuels produced from biomass-based feedstocks. To prevent adverse impacts on land use and biodiversity stemming from the increased harvest and cultivation of these feedstocks, the proposed Regulations would establish land-use and biodiversity (LUB) criteria. Only biofuels made from biomass feedstock that adhere to the LUB criteria would be eligible for compliance credit creation. These criteria apply to feedstock regardless of geographic origin. The criteria do not apply to feedstock that is not biomass (e.g. fuel made from direct air capture) or that is designated “low-concern biomass feedstock” (e.g. municipal solid waste).

The LUB criteria are separated into requirements specifically for forest feedstock, those specific for agricultural feedstock, and those that apply to all feedstock. These criteria also impose requirements for supply chain declarations (used to trace eligible material from the feedstock harvester to the biofuel producer) and material balancing (used to permit physical mixing of eligible and non-eligible feedstock). The onus for demonstrating criteria adherence rests with the biofuel producers, but compliance with the criteria would need to be demonstrated at the producer level or through an approved certification scheme.

Compliance Category 3, specified end-use fuel switching in transportation, enables credit creation for changing or retrofitting a fossil fuel combustion device to be powered by another fuel or energy source, such as electric vehicles (EVs). This does not directly reduce the CI of fossil fuels but reduces GHG emissions by displacing gasoline or diesel used in transportation by fuels or energies with lower CIs. Credits would be created by the owners or operators of a fuelling facility that supplies fuels for transportation uses (natural gas, renewable natural gas [RNG], hydrogen, propane, renewable propane), by the producers and importers of low CI fuels (RNG, hydrogen and renewable propane) used for transportation purposes, by the owners or operators of hydrogen fuelling stations for dispensing hydrogen to hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, by charging network operators for residential and public charging of EVs, and by charging site hosts for private or commercial charging of EVs. Credit for residential charging of electric vehicles would be phased out by the end of 2035 for charging stations installed by the end of 2030. Any residential charging station installed after the end of 2030 would not be eligible for credits after 2030. The proposed Regulations would require charging network operators to reinvest 100% of the proceeds from the sale of credits created by residential and public EV charging. The revenue would have to be reinvested into two available categories of actions: either reducing the cost of EV ownership through financial incentives to purchase or operate an EV, or expanding charging infrastructure in residential or public locations, including EV charging stations and electricity distribution infrastructure that supports EV charging.

A primary supplier may also use the compliance fund mechanism by contributing to an eligible “registered” funding program in order to satisfy up to 10% of its annual reduction requirement. The credit price under this mechanism would be set in the proposed Regulations at $350 in 2022 (consumer price index [CPI] adjusted) per compliance credit. The credits created by these investments cannot be traded and would expire if not used for that compliance period. Primary suppliers may create credits by contributing to a registered funding program between January 1 and June 30, as well as between November 1 and November 30 following the end of a compliance period.

Funds or programs within a fund that reduce CO2e emissions may be eligible to become a registered fund. The fund or program must operate in Canada, provide funding for projects or activities that support the deployment or commercialization of technologies or processes that reduce CO2e emissions, and provide publicly available annual audited reports. Any contributions to the fund must be used for projects or activities that reduce emissions within a five-year period from the time the contribution is made.

For primary suppliers unable to satisfy their reduction requirement by June 30 following the end of a given compliance period, a market-clearing mechanism that facilitates credit acquisition by primary suppliers would also be available. The proposed Regulations would set a maximum price for credits acquired, purchased or transferred in the credit clearance mechanism (CCM) at $300 in 2022 (CPI adjusted) per compliance credit. If there are not sufficient credits available in the CCM for all primary suppliers to satisfy their outstanding reduction requirement, each primary supplier would be eligible to acquire a prorated amount of the available credits. If the CCM is depleted of all pledged credits, primary suppliers with a shortfall must contribute to a registered funding program, up to the maximum of 10% of their CI reduction requirement. After satisfying those obligations, a primary supplier can carry forward up to 10% of its CI reduction requirement into a future compliance period, with a maximum deferral of two years. An interest of 20% is applied annually to any deferred amount.

The proposed Regulations would require the reporting of all credit trades, and all parties would be required to register and keep records. Annual compliance reporting to the Minister would be required for all primary suppliers and credit creators. The proposed Regulations would include validation and verification requirements. Most significantly, regulated parties would be required to obtain from an independent, accredited third-party verification body a report stating whether the information submitted is complete, compliant with the requirements, and credits and obligations are accurate and without material error. The Quality Assurance System would include requirements for most submitted applications and reports to be validated or verified by a third party, with accompanying validation or verification reports.

The Department is planning to publish the final version of the Regulations in late 2021. Once that happens, credit creators would be able to register and start to create credits. The final compliance period for the RFR would be 2022, with the final reporting and true-up period for the RFR occurring in 2023. The RFR would then be repealed on January 1, 2024.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Since the Government of Canada’s 2016 announcement of its commitment to develop a CFS, the Department has actively engaged with stakeholders from across the country on the design of the regulations. Since 2017, the Department has held extensive consultation sessions on the development of the proposed Regulations, including group meetings, technical webinars and bilateral meetings. Stakeholders in these sessions included industry (fossil fuel producers and suppliers, low carbon fuel producers and suppliers, emission-intensive and trade-exposed (EITE) sectors, and other various industry groups), provinces and territories, Indigenous Peoples, environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), administrators of similar programs in other jurisdictions (e.g. the California Air Resources Board) and academics. The Department has conducted hundreds of hours of bilateral meetings with individual stakeholders upon request in addition to participating in and chairing formal committees, as described below.

Publications

In February 2017, a discussion paper was published to gain initial views from stakeholders, provinces, and territories to inform the development of a regulatory framework in advance of developing specific regulations. The discussion paper laid out different approaches adopted by other jurisdictions, and posed technical questions related to the potential applicability of various elements within existing regulatory regimes at the time. The comment period closed on April 25, 2017, and the Department received over 125 comments from stakeholders. Following this, a Regulatory Framework was published in December 2017, outlining key design elements. Though no comments were formally requested, 47 comments were received and reviewed by the Department in early 2018.

In December 2018, a Regulatory Design Paper was published on the CFS website and in the Canada Gazette, Part I. The Regulatory Design Paper built on the two previous consultation documents and outlined the main design elements and approach for the proposed CFS Regulations for liquid fuels. Comments on the design paper closed on February 1, 2019, and over 100 comments from stakeholders, provinces, and territories and stakeholders were received. These comments informed the development of the proposed Regulations. Shortly after, a Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) Framework was published in February 2019, outlining the methodology for the CBA, which is part of this Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS). Following the release of the framework, extensive stakeholder consultation took place through committees, working groups and submissions on the Regulatory Design Paper, informing the regulatory development of the proposed Regulations.

In June 2019, the Proposed Regulatory Approach was published, building on the Regulatory Design Paper (2018), the Regulatory Framework (2017) and on the extensive stakeholder engagement on the previous publications (such as the discussion paper). The Proposed Regulatory Approach provided the full set of requirements and credit creation opportunities for liquid fuels. It was open for public comment until August 26, 2019, and the Department received 95 submissions with comments on the Proposed Regulatory Approach.

All publications mentioned above are accessible at the Government of Canada’s Clean Fuel Standard webpage.

Committees and working groups

The Department chaired several committees, which provided a forum for active engagement with stakeholders. These committees included a multi-stakeholder committee, a technical working group, and a task group specifically examining impacts to EITE sectors. Provinces and territories have also been heavily engaged in the consultations on the proposed Regulations and were participants on various committees, including a Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group. Engagement via these committees helped inform the more detailed aspects of the design of the proposed Regulations for the liquid fuel class, and will continue to operate through the development of the gaseous and solid fuel class regulations.

Established in January 2018, the Multi-Stakeholder Consultative Committee (MSCC) met periodically both via webinar and in-person to provide a forum for the Department to update interested parties on progress and to provide an opportunity for advice and input to be offered on the proposed Regulations. This Committee has a pan-Canadian representation from key industry associations, academia, ENGOs, provincial and territorial governments and other federal departments. Four meetings were held in 2018, with approximate attendance of up to 250 participants out of 700 invitees. In 2019, two meetings were held in July to present the Proposed Regulatory Approach, with an estimated 300 participants in attendance. One meeting of the MSCC was held in July 2020 to summarize proposed changes since 2019.

Established in January 2018, the Technical Working Group (TWG) consists of a smaller group of regulated parties and other key partners, such as representatives of the biofuel industry, provincial and territorial governments, and the electricity sector. Progress and feedback received from the TWG are reported back to the MSCC. In addition to the core TWG members, specific sectoral and technical experts have been invited to provide input on specific issues as they emerged. The TWG has approximately 60 members. Nine meetings (in-person and/or teleconferences) were held in 2018, five in 2019 and seven in 2020.

Established in January 2019, the EITE Task Group undertakes additional focused consultations regarding the proposed Regulations. The task group is a forum for the Department to listen to and understand concerns brought forward by EITE sectors and to explore credit creation opportunities for EITEs under the proposed Regulations. There are approximately 40 members, composed of one representative from each industry association participating in the Clean Fuel Standard TWG, as well as company TWG members not otherwise represented. Industry associations who are not members of the TWG but who are EITE sectors were invited. In total, five meetings were held in 2019 and representatives were invited to attend the June 2020 TWG sessions.

Two Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Groups were established as a forum for the Department to engage provincial and territorial counterparts on the development of the proposed Regulations. The first group is at the working-level and the second one is an Assistant Deputy Minister committee. Attendees included representatives from each province and territory. Five meetings were held in 2017, five meetings were held in 2018, three meetings were held in 2019 and two in 2020.

In addition to the specific committees mentioned above, the Department has conducted many ongoing bilateral meetings with interested parties and stakeholders since 2017. The proposed Regulations have also been raised within other forums, including the Multi-Stakeholder Committee on GHG Regulatory Measures and Programs and the Joint Working Group on the Future Vision for Canada’s Oil and Gas Industry. Overall, the Department has conducted hundreds of hours of bilateral meetings with provinces, territories, and individual stakeholders, in addition to participating and chairing formal committees.

Updates and engagement process since the 2019 Proposed Regulatory Approach

Since the Proposed Regulatory Approach was published in June 2019, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and further analysis of stakeholder feedback led to some updates to the design of the proposed Regulations. A key change relates to the CI stringency of the proposed Regulations. In June 2020, the Minister announced to the TWG that the stringency of the proposed Regulations would be changed in order to help mitigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on industry stakeholders and at the same time ensure that the proposed Regulations remain on track to deliver significant GHG emission reductions by 2030. The first three years of the proposed Regulations would see a reduction in stringency while the 2030 stringency has been increased from 10 gCO2e/MJ to 12 gCO2e/MJ. Other updates included more details on quantification methods, LUB criteria, the compliance fund mechanism and CCM, and a review process of the proposed Regulations. Material from these sessions is available upon request.

To inform these changes, two consultation sessions took place in June 2020 with the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Groups. Five consultation sessions were held in June 2020 with the TWG, and representatives from the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Groups and the EITE Task Group were invited to participate. These sessions included a focused session on updates to the CBA framework since February 2019. Following the June consultations, a session was held with the MSCC in July 2020 to present the proposed updates to the regulatory design. Bilateral meetings were also held throughout the summer of 2020 with stakeholders to further discuss their feedback on the updated regulatory design. Additionally, information sessions regarding LUB criteria, took place in July and August 2020 with Provincial and Territorial counterparts, as well as TWG members.

Engagement process for the development of the Lifecycle Analysis Model

To inform the development of the LCA Model which is required to support the implementation of the proposed Regulations, stakeholders have been engaged on this component since 2019. At the very initial stages of development of the Fuel LCA Model, stakeholders were engaged in reviewing the fossil fuel baseline values by participating in the CFS TWG and providing comments over the summer of 2019. Following this process, a critical review was carried out by a committee of technical and LCA experts that reviewed and commented on the methods and data used in the LCA of fossil fuel pathways to ensure conformity with lifecycle assessment requirements and guidelines set out in the ISO 14 040/44 standards by the International Standards Organization. Based on the critical review and stakeholders’ comments, the fossil fuel baseline values were updated.

An update on the Fuel LCA Model was provided during the summer of 2020 to the TWG, MSCC, EITE representatives and Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Groups in a series of webinars and bilateral meetings. In winter 2021, TWG members will have the opportunity to review the methodological approach used to develop the default low carbon fuel CI values and provide comments. Comments from stakeholders would be considered in updates to the methodology and for the low carbon fuel CI values throughout the summer of 2021.

Prior to the public launch of the Fuel LCA Model, the Department will form a Steering Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) with membership from industry, academia, the Government of Canada, and ENGOs that have expertise in life cycle assessment, GHG quantification, and/or GHG credit trading schemes. The role of the STAC is to provide ongoing technical support and feedback with respect to the development, update, and maintenance of the Fuel LCA Model. In addition, a provincial and territorial committee will be formed to act as a forum for discussion regarding how the proposed Regulations would interact with existing provincial and territorial policies and programs, and to identify any additional needs provinces and territories may have in relation to the Fuel LCA Model.

CEPA National Advisory Committee consultations

In accordance with subsection 140(4) of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 the Department offered to consult on the proposed Regulations with representatives from provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments through the CEPA National Advisory Committee.

Summary of key concerns

Stakeholders expressed a diverse range of views on the proposed Regulations, including concerns and recommendations on the various design elements outlined in the Proposed Regulatory Approach, preceding publications and the June 2020 consultations. A summary of the key issues is provided below.

Trajectory of the annual carbon intensity reduction requirement

A number of primary suppliers consulted were concerned that the annual CI reduction requirement in the 2019 Proposed Regulatory Approach was too high for the initial compliance year 2022, while others noted that the stringency overall was too high. Some argued that there was not enough lead-in time for new technologies and investments. In addition, primary suppliers expressed concerns about the potential for an insufficient supply of global biofuels, which would increase the risk of a shortfall of credits in the market. Primary suppliers and EITE stakeholders also recommended that the CI requirements be lowered for the first compliance year, compliance flexibilities (such as an earlier credit creation period, increased or unlimited cross-class credits trading) be expanded, and for a generic method for facility improvements to be established. These concerns have been reiterated during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic period, as the oil and gas sector continues to face financial and liquidity challenges due to low oil prices.

Low carbon fuel producers (i.e. credit creators) and ENGOs recommended that the stringency of the annual CI reduction requirement should be increased, or extended beyond 2030 to provide a long-term signal for clean fuel investments. In general, stakeholders recommended that a safeguard mechanism be in place to address unprecedented events, such as a public health pandemic, to temporarily suspend or scale back requirements under the proposed Regulations.

The design of the proposed Regulations takes into account the cost impacts for regulated parties to comply with its requirements. To assist with the oil and gas industry’s recovery from the economic and financial impacts associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, changes were made to the CI reduction requirements outlined in the 2019 Proposed Regulatory Approach and the proposed design that was consulted on in June 2020. For example, the CI trajectory starts later and at a lower level. The CI reduction requirements would come into force on December 1, 2022, instead of on June 1, 2022. The Department also decreased the CI reduction requirement in 2022 from 3.6 gCO2e/MJ to 2.4 gCO2e/MJ. These adjustments are intended to give primary suppliers additional time to make investments to meet their CI reduction requirements. To ensure CI reduction requirements remain on track to deliver significant GHG emission reductions by 2030, the Department has increased the CI stringency in 2030 from 10 gCO2e/MJ to 12 gCO2e/MJ. This decision was taken after a careful review of the state of the oil and gas sector and expected emissions reductions outcomes from the proposed Regulations.

In addition, the proposed Regulations allow early credit creation for actions as of registration of the final Regulations. Based on the stringency in the CI trajectory for primary suppliers, an increasing number of oil and gas corporations are expanding, or are considering expansion into low-carbon fuels to comply with the proposed Regulations.

Compliance Category 1: Greenhouse gas reductions along the lifecycle of fossil fuels to reduce carbon intensity

Several primary suppliers raised concerns regarding the potential for limited credit creation opportunities to comply with the proposed Regulations. As such, they requested greater flexibility to meet their CI reduction requirements (see trajectory and market design comments above). However, ENGOs, low carbon fuel suppliers, and end-use fuel switching credit creators have recommended that credits created from Compliance Category 1 be limited to a certain percentage of the annual obligation in order to ensure market signals are created to incentivize investment in low-carbon fuels. Regarding the quantification methods for credit creation presented in the June 2020 consultations, primary suppliers recommended the inclusion of an energy efficiency quantification method. During these consultations, a technology penetration rate of 5% was first considered as one of the criteria used to assess additionality. In other words, if a certain project type has a technology penetration rate higher than 5%, a technological or financial barrier would need to be identified in order to meet the criteria for additionality. Some provinces and EITEs also raised concerns on the additionality assessment and its 5% penetration rate requirement, noting the assessment is not aligned with other compliance categories and that the penetration rate is too low. Primary suppliers also expressed concern that the five-year crediting period that was initially proposed for eligible projects other than carbon, capture and storage is too short and has the risk to restrict credit creation opportunities. Lastly, primary suppliers recommended that it be possible to create credits retroactively, as of July 1, 2017.

The Department has carefully reviewed all comments received on reducing GHG emissions and meeting CI reduction requirements. In response to primary suppliers’ concerns regarding there being too few credit creation opportunities, the Department is undertaking the development of a generic quantification method in order to incent early investments and innovative technologies. Furthermore, the decrease in the 2022 CI reduction requirement and roll over of compliance units from the RFR would result in no additional action being required on behalf of primary suppliers in the first year of the proposed Regulations coming into force. The CI reduction requirement trajectory would then increase slowly and linearly year-over-year to allow lead time for investments, and the trajectory would be revised in 2030 to reflect the declining CI of fuels. Moreover, the first review of the proposed Regulations would allow the Department to take stock of the current state of fossil fuels and their CIs.

Concerning stakeholders’ recommendation to put a limit on credits created from Compliance Category 1, the Department found that placing a credit limit on this category for projects that are undergoing an additionality assessment at the project type level would go against the principal goals of the proposed Regulations, which is to reduce the lifecycle CI of fossil fuels and achieve incremental reductions. It would also reduce the compliance flexibility of the proposed Regulations and would decrease the availability of credits in the market. However, placing a credit limit of 10% while developing separate and more streamlined additionality criteria at the project level for the generic quantification method would provide compliance flexibility while mitigating risks associated with the additionality assessment. Given that all other quantification methods would undergo the additionality assessment at the project type level, there is no credit limit on all other project types.

Concerning the quantification methods, the Department is now developing a generic quantification method. Projects such as energy efficiency, cogeneration, electriciation and methane reductions could be recognized under the generic quantification method (QM) provided they meet the eligibility criteria. Existing quantification methods would be eliminated as incremental technological innovation becomes business as usual and new quantification methods would be added as clean technology advances. Regarding the penetration rate of 5%, one of the criteria used to assess additionality in all quantification methods other than the generic quantification method, the Department has added an additional flexibility: the penetration rate must be less than 5% or no more than five facilities, which is appropriate. As long as one of these criteria is fulfilled, then no further assessment of additionality is needed, reducing burden. This added flexibility recognizes that in some sectors with few facilities, the 5% may be more easily exceeded and provides another option of no more than five facilities as an alternative threshold. On the crediting period, the Department changed the time period to 20 years with one renewal period of 5 years for carbon capture and storage projects and 10 years with one renewal period of 5 years for other projects to better align with existing provincial and federal regulations (such as the Alberta Emission Offset System) and carbon credit systems.

Compliance Category 2: Supplying low-carbon fuels

A number of low carbon fuel producers and ENGOs emphasized the need to have a strong demand signal for low carbon fuel investment, with concerns that the inclusion of compliance flexibility mechanisms (such as the compliance fund mechanism) and the adoption of Compliance Category 1 would impede this signal. Limiting compliance through Compliance Category 1, increasing the stringency of the CI target, or including a safety net that would review the level of compliance through this category in 2025 was recommended to support a market signal for low-carbon fuels. The Department expects that the stringency of the proposed Regulations in 2030 is high enough that there would be sufficient demand for biofuels (more detailed analysis on this is provided in the section on Benefits and costs).

Feedstock availability concerns were raised regarding the supply for low-carbon fuels, as well as concerns on indirect land-use change and implications to biodiversity. On feedstock availability, some primary suppliers and low carbon fuel producers highlighted a risk for low feedstock supply, in particular for advanced biofuels, and its implications for credit creation. They voiced concerns that existing technologies for advanced biofuels are not currently commercially viable and therefore could not significantly contribute to reducing liquid fossil fuel CIs. Some stakeholders also suggested the use of mass balance to align with other jurisdictions that have implemented regulatory requirements for credit creation.

The Department has reviewed all comments received relating to low-carbon fuels and feedstock and has considered their implications for the design of the proposed Regulations. The Department expects that there would be sufficient supply of low-carbon fuels to enable compliance with the proposed Regulations in 2030 (see section on Compliance Category 2: Supplying low-carbon fuels for more detail).

Land-use and biodiversity criteria

As a signatory to the international Convention on Biological Diversity, Canada is committed to responsible stewardship of its biological resources and to the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. To prevent negative land use and biodiversity impacts from increased harvesting of feedstock for biofuel production, the Department released the proposed Land Use and Biodiversity (LUB) criteria for the proposed Regulations in April 2019. Only feedstocks that adhere to the LUB criteria would be able to create credits under the proposed Regulations.

Comments on the first iteration of the LUB criteria largely centred on preventing land-use change in areas with high carbon stock, how crops associated with high indirect land-use change (ILUC) would be treated, and how sustainable management of forest harvesting would be ensured. Some credit creators requested the inclusion of quantified CI factors to incorporate indirect land use change. A second draft of the criteria was published in August 2019.

The Department proposed several changes to the LUB criteria to the TWG in June 2020. Those proposed changes sought to strengthen some aspects of the LUB criteria, and to ensure the criteria are measurable and verifiable. The changes also added a list of feedstock types exempt from the LUB criteria, modified the material balance approach, and revised the definitions of forest, grassland, and wetland.

The proposed Regulations include additional changes made following the June 2020 consultation sessions with stakeholders. The June proposal prohibited credit creation for feedstocks harvested in any protected areas designated by international organizations. The proposed Regulations respond to recommendations from provinces and territories by limiting this restriction to protected areas designated by international organizations if they have been ratified by the national and sub-national jurisdictions in which the feedstock was harvested.

Other comments related to the risk of fraud related to the list of feedstocks not subject to the LUB criteria, citing experience in the EU where some feedstocks have been falsely claimed to be waste (which is not subject to the EU’s equivalent of the proposed LUB criteria). Some stakeholders requested that criteria be revisited that prevent credit creation for feedstocks harvested within 30 meters of a water body (i.e. in riparian zones). Many suggested that adherence to existing provincial riparian zone regulations should satisfy the LUB riparian criterion. On crop expansion requirements that prevent credit creation for feedstocks harvested in forests, wetlands and grasslands since 2008, the Department received comments noting that there is insufficient GIS data for the proposed 2008 baseline. Finally, several stakeholders recommended that the proposed Regulations recognize that adherence to provincial requirements for agriculture and forestry practices should satisfy all of the proposed Regulation’s LUB criteria, and aggregate compliance was also requested as an option for credit creators to come into compliance with the LUB criteria.

Following extensive discussions and analysis after the June 2020 consultation sessions, the Department made changes to its proposed LUB criteria requirements. The proposed Regulations provide that any land designated by an international agreement as protected must also be recognized by the jurisdiction to be considered ineligible land for the CFS feedstock harvesting. To address the risk of fraud, the proposed Regulations do not include the “waste multiplier” that is in the EU system to create additional incentives for the use of waste feedstock. For riparian zones, the proposed Regulations recognize national and regional riparian regulations that protect against adverse LUB impacts, include a grandfathering clause to allow credit creation for feedstocks harvested in any riparian zones that were harvested prior to 2020, and allow feedstocks from harvesting in forest riparian zones if the forest harvester has management practices in place to protect the riparian zones and related water bodies. For crop expansion requirements, the Department changed the baseline from January 2008 to January 2020 to better align with the first official signal of the proposed Regulations. As a response to concerns regarding burden and duplication created by the LUB criteria with provincial regulations, the proposed Regulations enable recognition of national or sub-national regulatory frameworks that align with the LUB criteria on a criterion by criterion basis.

Consultations with provinces and territories during the summer of 2020 led to refinement of the indicators that could be used to prove compliance with the LUB criteria in the event of an audit, and to the development of the information requirements for using an aggregate compliance approach in which all suppliers in a jurisdiction that has rules aligned with the LUB criteria would be deemed eligible.

Compliance Category 3: Specified end-use switching in transportation

Electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), and electricity utilities generally recommended that they would each be best suited as default credit creators for residential EV charging; however, charging network operators supported utilities as the default credit creator. Utilities highlighted that they are in a better position to understand the sources of electricity being supplied to the grid and the associated CIs. Utilities also believe they are best suited to promote EVs and to invest in infrastructure to support electrification while mitigating costs to the electrical grid and all end users of electricity. Alternatively, primary suppliers generally supported OEMs as default credit creators for EV charging under Compliance Category 3. That being said, OEMs expressed concerns that opportunities to create credits would not be significant, sustained, secure or predictable.

Overall, the majority of stakeholders are supportive of requirements that, in order to be eligible to create credits, home charging data must be accurately measured and of requirements to reinvest the credit revenue resulting from home charging data. Stakeholders were opposed to phasing out credit creation for residential EV charging, noting that would be premature to do so before adoption of EVs becomes common practice in the Canadian market. However, primary suppliers recommended that if they are a charging network operator and create credits for residential or public EV charging to satisfy a portion of their CI reduction requirement, there should be no reinvestment requirement associated with a credit that has not been sold. A few stakeholders recommended eliminating revenue reinvestment requirements altogether, and others suggested expanding the scope of reinvestment requirements to other activities such as education and awareness of EVs. Additionally, some stakeholders recommended expanding end-use fuel switching beyond transportation.

In June 2020, the Department presented a revised proposal for EV credit creation to stakeholders, which included a proposal to phase out residential EV charging credits from 100% in 2026 to 0% in 2030. The Department has reviewed the comments received and assessed the proposed June 2020 approach to end-use fuel switching in transportation. The proposed Regulations were updated to reflect comments received. The default credit creator for residential EV charging would be charging network operators for homes equipped with network-connected charging stations. Credit for residential charging of electric vehicles would be phased out by the end of 2035 for charging stations installed by the end of 2030. Any residential charging station installed after the end of 2030 would not be eligible for credits after 2030. In the proposed Regulations, parties that have the legal right to ownership of the data regarding the amount of electricity that is supplied to EVs and the time it is supplied through network-connected charging stations can create credits. Charging network operators would be required to reinvest 100% of the revenues generated from the sale of credits from residential and public EV charging in financial incentives for EV owners or buyers and expanding charging infrastructure in residential or public locations. There would not be revenue reinvestment requirements for primary suppliers that use their own credits to satisfy a portion of their reduction requirements.

Based on the Departmental analysis, EVs are expected to create the majority of end-use fuel switching credits, where the market can provide significant opportunities for credit creation. At this time, the Department is not considering extending end-fuel switching beyond transportation.

Many stakeholders expressed the desire for additional clarity around how energy efficiency ratio (EER) values were determined. EER values were developed to be representative of the types of vehicles in use in Canada, leading to credit creation based on a comparison to the vehicles being displaced. The EER values would be reviewed over time and may be updated as the energy efficiency of various technologies change over time, and as other more specific fuel and vehicle applications are introduced to the market.

Credit market design

Primary suppliers raised concerns over the credit market design, and the potential for credit shortages. As a way to address shortages in credit supply, primary suppliers recommended greater flexibility, including unlimited exchange of credits between different fuel classes, no restriction on credit banking and unrestricted use of the compliance fund mechanism. On the other hand, some credit creators raised concerns that a surplus of credits or compliance flexibilities would limit the demand for low-carbon fuels, affecting investments in this sector.

To reduce the risk of a credit shortage, the 2022 CI reduction requirement was lowered in comparison to what had been outlined in the June 2019 Proposed Regulatory Approach. A slow, linear increase of the CI trajectory over time is expected to allow sufficient lead time for investments. In addition, the proposed Regulations impose limits on the proposed flexible compliance options. These include a 10% limit of payment into the compliance fund mechanism, a 10% limit on the trading credits across fuel classes, and a 10% limit on carrying forward a credit obligation. These limits help ensure that a market signal supports investments in low-carbon fuels.

A number of stakeholders requested regular departmental reports on the proposed Regulations using aggregated indicators, such as credit totals, trades and average credit price. The Department plans to release reports using aggregated indicators.

Compliance flexibilities / market stability mechanisms

Credit Clearance Mechanism

Primary suppliers and some provinces raised concern that the price cap of the Credit Clearance Mechanism was too high, while low-carbon fuel suppliers, end-use fuel switching credit creators, and ENGOs noted the price cap was too low. Both stakeholder groups expressed concern that the price ceiling would affect market signals for investments in their respective sectors.

The Credit Clearance Mechanism serves to provide some price certainty to both primary suppliers and credit creators. The Department reviewed existing credit clearing mechanisms in other jurisdictions in the context of a Canadian market. The Department set a credit clearance ceiling price based on a review of credit costs expected in the credit market and the price cap of similar credit clearance mechanisms in California and Oregon.

Compliance fund mechanism

Primary suppliers and some provinces raised concerns that the price ceiling of the compliance fund mechanism is too high, while credit creators and ENGOs noted that the price ceiling is too low. Both stakeholder groups noted that the price ceiling would affect market signals for investments in their respective sectors. In addition, several provincial stakeholders recommended that revenues generated from the compliance fund mechanism be invested in relevant GHG emission reduction programs at the provincial and territorial level.

The compliance fund mechanism ceiling price represents an upper bound of credit costs expected in the credit market. It is expected that many compliance actions would be undertaken at lower cost.

Revenues from the compliance fund mechanism would be disbursed to applicable provincial and territorial programs that meet the criteria set out in the proposed Regulations.

Exemptions

Several stakeholders recommended that certain sectors be exempted from the proposed Regulations, including rail, marine and aviation. Stakeholders noted that these sectors represent a small portion of domestic consumption of fossil fuels, are subject to international standards, and cost-effective emission reduction pathways are largely non-existent. Alternatively, some stakeholders recommended credit creation under the proposed Regulations for domestic aviation fuel. There was a consensus among stakeholders for continued discussions on the proposed Regulations, the Output-Based Pricing System Regulations and international regimes, such as the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation.

The International Maritime Organization adopted an interim strategy for GHG emissions in 2018, which will be reviewed in 2023. The Department supports the International Maritime Organization as the appropriate forum to address international maritime shipping emissions, and the work it has undertaken to address these emissions. Therefore, liquid fuels for international marine use would not be subject to the proposed Regulations. The International Civil Aviation Organization’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation is mitigating GHG emissions from international aviation. The Government of Canada supports the International Civil Aviation Organization as the appropriate forum to address international aviation emissions, and the work it has undertaken to address these emissions. Therefore, jet fuel that is used for international flights would not be subject to the proposed Regulations. The treatment of domestic aviation fuels and credit creation for low CI aviation fuels is still under consideration, and is being examined in conjunction with carbon pollution pricing policies. However, aviation gasoline – the fuel that is used in smaller, piston engine aircrafts (e.g. a Cessna) – would not be subject to the proposed Regulations. According to the Department’s GHG inventory and projections from the Departmental Reference Case, the volume of aviation gasoline used in Canada is low (unlike jet fuel, for example) and its contribution to Canada’s overall annual GHG emissions is low. In addition, aviation gasoline certification bodies have not yet focused on suitable low CI gasolines for aviation use. Instead, they remain focused on finding unleaded aviation gasoline alternatives.

Regional implications