Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 155, Number 52: Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations

December 25, 2021

Statutory authority

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Sponsoring departments

Department of the Environment

Department of Health

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: Current scientific evidence indicates that macroplastic pollution poses an ecological hazard, including physical harm, to some animals and their habitat. Canadians consume substantial quantities of single-use plastic manufactured items (SUPs) every year. These SUPs are designed to be discarded once their single use has been fulfilled. A share of that waste becomes plastic pollution. Action is needed to restrict or eliminate SUPs that pose a threat of harm to the environment.

Description: The proposed Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations (the proposed Regulations) would prohibit the manufacture, import, and sale of six categories of SUPs (i.e. checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, ring carriers, stir sticks, and straws). Manufacture and import for the purposes of export would not be subject to the proposed prohibition. Checkout bags, cutlery, and straws have reusable substitutes so the proposed Regulations would identify performance standards to differentiate between single-use and reusable items for these three product categories. The proposed Regulations would also provide exemptions to accommodate people with disabilities. These exemptions are linked to the conditions upon which straws are sold. Therefore, the prohibitions on sale of straws would come into force one year after the proposed Regulations are registered. The prohibition on sale for all other single-use items would come into force two years after the proposed Regulations are registered. The prohibitions on manufacture and import of all six single-use items would come into force one year after registration of the proposed Regulations.

Rationale: Plastics are among the most universally used materials in modern society. Single-use consumer items are often the most commonly collected items in litter clean-ups, with plastic being the most common material recovered in both domestic and international clean-up efforts. The six categories of SUPs subject to the proposed Regulations represented an estimated 160 000 tonnes sold in 2019, or an estimated 5% of the total plastic waste generated in Canada in 2019.

The proposed Regulations would support the federal, provincial, and territorial governments’ Strategy on Zero Plastic Waste. Several provincial, territorial, and municipal jurisdictions have already enacted prohibitions or standards for certain SUPs. On October 7, 2020, the Department of the Environment (the Department) published a discussion paper on the Canadian Environmental Protection Act Registryfootnote 1 outlining a proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution. During the ensuing 60-day public comment period, the Department received 205 written submissions representing the views of 251 stakeholder groups (156 industry members; 38 provincial, territorial, or municipal governments; 3 Indigenous groups; 32 non-governmental organizations; and 22 other groups). In addition, the Department received over 24 000 emails from individual Canadians, and an online petition started by a civil society group that received over 100 000 signatures. Overall, support for the proposed Regulations has been mostly positive from environmental non-governmental organizations and local governments and negative from some industry stakeholders. Other industry stakeholders have announced or have begun transitioning away from using SUPs. Support for the proposed Regulations from provincial and territorial governments has been mixed.

The proposed Regulations are expected to result in a net decrease of approximately 1.4 million tonnes in plastic waste over a 10-year period (2023–2032), which would represent around 4% of the total estimated plastic waste generated in Canada each year. It would also result in a decrease of around 23 000 tonnes in plastic pollution over the same period, which would represent 7% of the total plastic pollution generated each year. The proposed Regulations are expected to result in $1.9 billion in present value costs over the analytical period. While these costs are significant in aggregate, they would be widely dispersed across Canadian consumers (around $5 per capita per year). The proposed Regulations would also result in $619 million in present value monetized benefits over the analytical period, stemming mainly from the avoided cost of terrestrial litter clean-up. The costs and monetized benefits of the proposed Regulations would therefore be $1.3 billion in present value net cost over the analytical period. Given the extent of ecological harm that can be inflicted to wildlife and their habitats from the plastic pollution of the six categories of SUPs, and the reduction of enjoyment of ecosystem goods and services by Canadians, the associated non-monetized benefits are expected to be significant.

Issues

The Canadian economy generates large amounts of plastic waste every year, of which a certain proportion enters the environment as plastic pollution. Current scientific evidence indicates that macroplastic pollution causes physical harm to wildlife on an individual level and has the potential to adversely affect habitat integrity. Single-use plastic manufactured items (SUPs) are significant contributors to plastic pollution, as they are designed to be discarded once their single use has been fulfilled. Preventing pollution and waste is an area of shared jurisdiction between all levels of government in Canada, and plastic pollution from certain SUPs is an issue with national and international dimensions that cannot be effectively eliminated through provincial, territorial, or local measures alone. Therefore, the Minister of the Environment (the Minister), in accordance with section 93 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA or “the Act”), is recommending that the Governor in Council propose to eliminate or restrict six categories of SUPs subject to the proposed Regulations. These categories are the following: checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, ring carriers, stir sticks, and straws (hereafter referred to as the “six categories of SUPs”).

Background

Lifecycle of plastic manufactured items in the Canadian economy

Plastics are among the most universally used material in modern society. Plastics are low-cost and durable and are used in a wide range of applications, such as packaging, construction materials, automotive materials, electronics, textiles, and medical and personal protective equipment. Plastics can be created from a wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic organic compounds and are formed from long-chain polymers of high molecular mass that often contain chemical additives. Different polymers can be manufactured using different compositions of petroleum products, plant-based starting material, or recycled and recovered plastics. Plastic manufactured items can be formed into a specific physical shape or design during manufacture and serve many different functions. They can include final products, as well as components of products. The scientific literature often categorizes plastic pollution by size, in an environmental context. Individual pieces of plastic that are less than or equal to 5 millimetres (mm) in size are referred to as microplastics, while those that are greater than 5 mm in size are referred to as macroplastics. Microplastics can be “primary microplastics” (intentionally produced micro-sized plastic particles), or “secondary microplastics” (micro-sized plastic particles resulting from the breakdown of larger plastic manufactured items).

The proper management of plastic manufactured items is a global issue as millions of tonnes of plastics are produced each year around the world. It is estimated that half of the plastics produced each year are for single-use items.footnote 2 In 2020, 367 million tonnes of plastic were produced globally, a 0.3% decrease from 2019.footnote 3 The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a decrease in production for the packaging sector, though individual consumption of plastic manufactured items may have increased (see the “Benefits and costs” section for more information on the estimated effects).

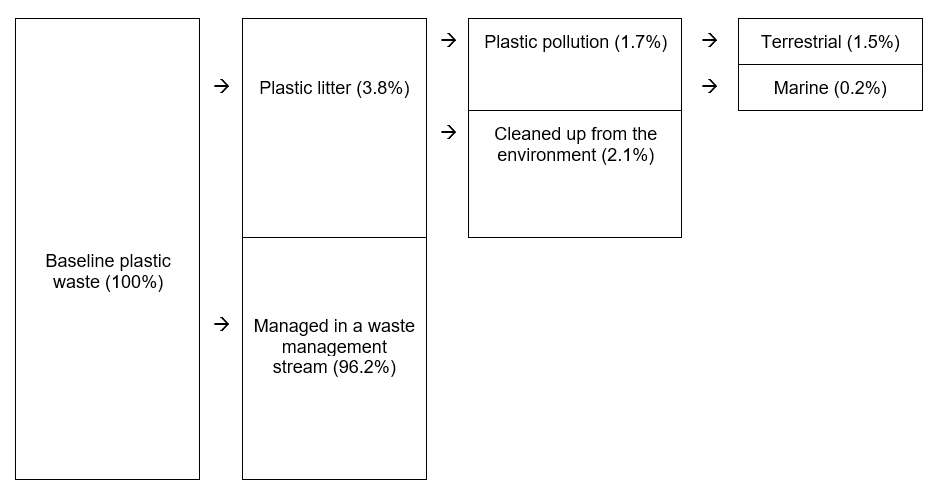

In order to better understand the quantities, uses, and end-of-life management of plastics in the Canadian economy, the Department of the Environment (the Department) commissioned the Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste (the Deloitte Study), which was published in 2019. As displayed in Figure 1, the Deloitte Study found that approximately 4.7 million tonnes of plastic resins (raw materials) were introduced to the domestic market in 2016, while approximately 3.3 million tonnes of plastic manufactured items became plastic waste. The packaging sector alone accounted for 43% (approximately 1.4 million tonnes) of all plastic waste generated, as the vast majority of packaging is designed to become waste after fulfilling a single use. Of the 3.3 million tonnes of plastic waste generated nationally in 2016, 2.8 million tonnes (86%) were landfilled, 300 000 tonnes (9%) were recycled, 137 000 tonnes (4%) were incinerated with, or without, energy recovery, and 29 000 tonnes (1%) became plastic pollution, of which 2 500 tonnes were marine plastic pollution. Using those numbers, Canadians produced around 800 grams of plastic pollution per capita in 2016. If observed market trends were to continue, the Deloitte Study estimates that the 2016 figures for plastic waste and plastic pollution could increase by roughly one third by 2030.

Figure 1. Canadian plastic flow in thousands of tonnes (2016)

Figure from the Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste, p. ii

Figure 1. Canadian plastic flow in thousands of tonnes (2016) - Text version

Diagram from the 2019 Deloitte Study illustrating the flow of plastics through the Canadian economy in 2016. To start, 4 667 kilotonnes of plastic resins (raw materials) were used in products that were introduced to the domestic market, from which 3 268 kilotonnes of plastics in products were discarded as waste. Of the 4 667 kilotonnes of plastic resins that were used in end-use applications, 3 068 kilotonnes became durable plastics and 1 599 kilotonnes became nondurable plastics. Durable plastics generated 1 681 kilotonnes of waste, and nondurable plastics generated 1 587 kilotonnes of waste, resulting in 3 268 kilotonnes of plastic waste generated in 2016. Of the 3 268 kilotonnes of plastic waste generated nationally, 2 795 kilotonnes (86%) were landfilled, 305 kilotonnes (9%) were recycled, 137 kilotonnes (4%) were incinerated with energy recovery, and 29 kilotonnes (1%) ended up in unmanaged dumps or were leaked into the environment. Of the 305 kilotonnes of plastic waste recycled, 256 kilotonnes were processed through mechanical (polymer) recycling, while 40 kilotonnes were processed through chemical recycling from disposed waste, and 9 kilotonnes were processed through chemical recycling from diverted waste.

Figure 1 also illustrates the Deloitte Study’s finding that the current Canadian plastics economy is mostly linear, as opposed to circular. Under a linear economy, plastic manufactured items follow a unidirectional path: production from mostly virgin (as opposed to recycled) materials, usage (until no longer deemed useful), and then disposal into the waste stream, mostly for landfill. Put another way, most plastic manufactured items in a linear economy are produced from virgin resins, and their value is not recovered at the end of their useful life. Therefore, most of the plastic waste generated in Canada enters landfills and exits the economy, representing a significant potential lost economic opportunity.

By contrast, a circular economy is a model of production and consumption that recovers and restores products, components, and materials through strategies like reuse, repair, remanufacture or (as a last resort) recycling.footnote 4 In a circular economy, plastic manufactured items would be produced by a number of different pathways, one of which includes using recycled resins. Their value would be recovered at the end of their useful life to be reintegrated into the economy. In this way, the end of the value chain for one manufactured item becomes the start of the value chain for another, thereby extending life cycles and resulting in fewer adverse environmental impacts.

There are many factors contributing to the linear nature of the plastics economy in Canada, including the following:

- virgin and recycled plastic resins compete: competition is difficult for the recycling industry because of inconsistent feedstock composition and a more labour-intensive cost structure compared to virgin resin production, which can take advantage of economies of scale;

- weak end-markets for recycled plastics: in some cases, recycled resins are a cheaper substitute for product manufacturers, for example for use in less demanding applications, but overall, the inconsistent supply of quality feedstock at a competitive price undermines the establishment of viable and lasting end-markets;

- collection rates are low: only 25% of plastics are collected and sent to a sorting facility in Canada according to the Deloitte Study (through curbside collection, recycling depots, or deposit-refund systems), and only around a third of collected plastics are effectively recycled because of contamination, infrastructure deficiencies, and lack of end-markets;

- insufficient recovery options: current near absence of high-volume recovery options, losses from existing processes, and competition from low-cost disposal substitutes, such as landfills, point to the need for investments in innovation and infrastructure, in particular to commercialize and scale up new technologies; and

- cost of plastic pollution is shouldered by individuals and communities: the responsibility for preventing and managing land-based sources of plastic pollution, such as urban and roadside litter, is largely shouldered by municipalities, civil society organizations, and volunteers, at a great cost.

The Deloitte Study estimated that 2 500 tonnes of the plastic waste generated in Canada in 2016 entered the oceans as plastic pollution, while the amount of plastic pollution entering Canadian freshwaters (e.g. the Great Lakes, other lakes, rivers) but never reaching the oceans is unknown. Internationally, academic studies have estimated the total amount of plastic pollution entering oceans globally at between 8 million tonnes and 13 million tonnes per year.footnote 5 In fact, plastics constitute the most prevalent type of litter found in the oceans, estimated to make up at least 80% of total marine debris (from surface waters to deep-sea sediments), plastic bags being among the most prevalent littered items.footnote 6

The Deloitte Study indicates that one of the key pathways for plastic waste to become terrestrial or marine plastic pollution is people dropping litter on the ground or directly into aquatic environments. An estimated 80% of all marine plastic pollution originates on land and is transported to the ocean via wind or rivers, with the remaining 20% attributable to fishing activities, natural disasters, and other sources.footnote 7 Once plastic pollution reaches oceans, the majority will slowly weather and fragment into microplastics, accumulate on shorelines, sink to the seabed, or float on the sea surface, but will never fully decompose.

Plastic pollution is found on the shorelines of every continent, with greater proliferation typically found near tourist destinations and densely populated areas. Large-scale marine and freshwater litter clean-ups are very costly, and therefore, limited in practice. While such clean-ups may result in temporary benefits, they do not alter the inflow of plastic pollution into marine or freshwater environments, and must therefore be frequently repeated for sustained benefits to be realized. For this reason, preventing plastic pollution from entering the environment in the first place is often seen as the only viable approach to successfully managing the issue of marine plastic pollution on a long-term basis.footnote 7

Science Assessment of Plastic Pollution

In October 2020, the Department of the Environment and the Department of Health published a Science Assessment of Plastic Pollution (the Science Assessment) on the Canada.ca (Chemical Substances) website. The intent of the Science Assessment was to summarize the current state of the science regarding the potential impacts of plastic pollution on the environment and human health, as well as to inform future decision-making on plastic pollution in Canada. The Science Assessment found that macroplastic and microplastic pollution are ubiquitous in the environment. The Science Assessment also found that many sources of release contribute to plastic pollution, and that the potential effects of microplastics on individual animals, the environment, and human health are unclear and require more research.

With respect to macroplastic pollution, the Science Assessment found evidence of adverse effects, including mortality, to some animals through

- entanglement, which can lead to suffocation, strangulation, or smothering;

- ingestion, which can block airways or intestinal systems leading to suffocation or starvation; and

- transport of invasive species into well-established ecosystems or transport of diseases that can alter the genetic diversity of an ecosystem when they use the plastic pollution as a vessel for rafting.

Overall, the Science Assessment recommended pursuing immediate action to reduce the presence of plastic pollution in the environment, in accordance with the precautionary principle as defined in section 2 of CEPA.

Government action on plastic waste and plastic pollution

The Government of Canada has committed to taking action to reduce plastic waste and plastic pollution through several avenues. In November 2018, through the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, the federal, provincial, and territorial governments approved, in principle, a Canada-wide Strategy on Zero Plastic Waste (PDF) (the Strategy). The Strategy takes a circular economy approach to plastics and provides a framework for action in Canada. Federal, provincial, and territorial governments are collaborating to implement the Action Plan on Zero Plastic Waste (the Action Plan), for which Phase 1 (PDF) and Phase 2 (PDF) were approved in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

In October 2020, the Government published a discussion paper entitled A proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution (the Discussion Paper). The Discussion Paper outlined a proposed integrated management approach that addresses the entire life cycle of plastics to prevent plastic waste and plastic pollution. The Government described a suite of measures to be developed under CEPA to implement the integrated management approach, which will seek to

- manage single-use plastics using a management framework;

- establish performance standards for plastic products to reduce (or eliminate) their environmental impact and stimulate demand for recycled plastics; and

- ensure end-of-life responsibility, so that companies that manufacture or import plastic products or sell items with plastic packaging are responsible for collecting and recycling them.

Responses to the Discussion Paper received from stakeholders, partners, and the public are presented in detail in the “Consultation” section.

Based on the findings of the Science Assessment and other available information, the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health (the ministers) were satisfied that plastic manufactured items met the ecological criterion for a toxic substance as set out in paragraph 64(a) of CEPA. In order to develop risk management measures under CEPA to address the potential ecological risks associated with certain plastic manufactured items becoming plastic pollution, the Administrator in Council made an Order adding plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1 to CEPA, which was published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on May 12, 2021. The listing enables the ministers to propose risk management measures under CEPA that could target the sources of plastic pollution and change behaviour at key stages in the life cycle of plastic products, such as product design, manufacture, use, disposal, and value recovery.

Most prevalent items contributing to plastic pollution

Internationally, single-use consumer items are often the most commonly picked up items in litter clean-ups, with plastic being the most common material recovered. The top 10 items reported in the Ocean Conservancy International Coastal Cleanup 2020 report (in which Canada participated) were food wrappers, cigarette butts, plastic beverage bottles, plastic bottle caps, straws and stir sticks, plastic cups and plates, plastic grocery bags, plastic take-out containers, other plastic bags and plastic lids. Since 2017, the top 10 items collected each year have all been made of plastic. Similarly, data based on total items collected over time from the European Environment Agencyfootnote 8 shows that the most common category of items found as marine litter on the beach are cigarette butts, plastic caps and drink lids, shopping bags, string and cord food wrappers, cotton bud sticks, drink bottles and food containers. Based on material, plastic was found to account for 87% of all materials collected over time.footnote 9

Domestically, a separate clean-up effort in 2019, the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup,footnote 10 also found cigarette butts, food wrappers, bottle caps, plastic bags, plastic bottles and straws in their top 10 most commonly found litter items. The top 10 accounted for over 1.6 million items collected in Canada in 2019. The weight of all items collected in 2019 was almost double the weight of all items collected in 2017. Other common plastic items found in shoreline clean-up data include cutlery, ring carriers, cups, pieces of foam and plastic fragments, and personal hygiene products.

Despite the differences in the number of items recovered in each item category, some item categories are considered more environmentally problematic in terms of being more harmful to wildlife or the environment in general, based on their material, weight and shape or structure. Of common consumer items made of plastic, plastic bags have been found to pose one of the greatest impacts to marine wildlife.footnote 11 Plastic bags are light-weight and usually have looped handles, meaning wildlife can become entangled in their handles. Plastic bags and utensils have been rated the greatest risk in terms of ingesting plastic items for seabirds, turtles and marine mammals.footnote 11 Ring carriers can also pose a threat of entanglement as they also have a looped structure. Many of the consumer items frequently picked up in litter clean-ups are also considered to be value recovery problematic as they are made of problematic plastics that have very low recycling rates.

Government action with respect to single-use plastic manufactured items

In June 2019, the Prime Minister announced a commitment for the Government of Canada to take steps to reduce plastic waste and plastic pollution, including working with provinces and territories to introduce standards and targets that would make companies that manufacture plastic products or that sell items with plastic packaging responsible for their plastic waste. In the same announcement, the Prime Minister committed the Government of Canada to banning harmful SUPs as early as 2021, where warranted and supported by scientific evidence, and reaffirmed this commitment in the Mandate Letter to the Minister of the Environment in December 2019 and in the Speech from the Throne in September 2020.

In order to determine which SUPs are considered harmful and warrant prohibition in Canada, the Department developed a management framework for categorizing SUPs (the Framework), as presented in the Discussion Paper. The Framework categorized a wide selection of SUPs commonly collected as litter or otherwise flagged by other jurisdictions (e.g. different types of bags, different types of packaging, cigarette filters, coffee pods) as either environmentally problematic, value-recovery problematic, or both. As outlined in the Discussion Paper, in order for a SUP to be considered harmful such that a ban would be warranted and supported by science, the SUP in question must meet the environmentally problematic and value recovery problematic criteria using scientific evidence to assess environmental prevalence and value recovery challenges, with consideration for exemptions for certain essential functions. After evaluating the wide selection of SUPs in this way, the Framework identified six harmful SUPs, or categories of SUPs identified by utility, warranted for prohibition or restriction in Canada.

- Checkout bags. Also known as shopping bags, grocery bags, or carryout bags. These items are typically given to customers at the retail point of sale to carry purchased goods from a business. They are typically (but not exclusively) made from high- or low-density polyethylene film and may or may not have handles. SUP checkout bags have low recycling rates (estimated at less than 15%) despite being accepted in several recycling programs across Canada, and are known to hamper recycling systems by becoming caught up in sorting and processing machinery. They are some of the most common forms of plastic litter in the natural environment (e.g. 31 164 units were collected from Canadian shorelines in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). Checkout bags have been identified by experts as posing a threat of entanglement, ingestion and habitat disruption among marine wildlife;

- Cutlery (knives, forks, spoons, sporks and chopsticks). These items are typically given to customers by restaurants and other food vendors to eat quick-service or takeout food, though they can also be purchased in bulk at many retail businesses such as grocery or dollar stores. They are typically (but not exclusively) made from polypropylene or polystyrene. SUP cutlery have low recycling rates (estimated at close to 0%) and are typically not accepted in provincial or municipal recycling systems. They are common forms of plastic litter (e.g. 10 772 units were collected from Canadian shorelines in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). Cutlery litter has been ranked as high by experts in terms of the threat posed to wildlife;

- Foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics. This category includes clamshell containers, lidded containers, cartons, cups, plates and bowls used for serving or transporting prepared food or beverages (i.e. that is ready to be consumed without any further preparation, such as cooking, boiling or heating). This category of SUPs only includes those made from extruded or expanded polystyrene foam, polyvinyl chloride, oxo-degradable plastics, or that contain the additive “carbon black.” When littered in the environment, foodservice ware may be placed in a range of categories, depending on the kind of plastic used (e.g. expected to form part of the total units collected under the categories of foam [24 213 units], food wrappers/containers [74 224 units], or tiny pieces of plastic or foam [595 227 units] in the 2019 Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). Foodservice ware in the form of expanded polystyrene containers, takeout containers, cups and plates and plastic food lids have all been ranked as high by experts in terms of the threat posed to wildlife;

- Ring carriers (typically known as six-pack rings). Ring carriers are deformable bands that are placed on beverage containers (e.g. cans, bottles) to package them for transport. They can be cut to hold different multiples of containers (e.g. two-packs, eight-packs). They are typically made from low-density polyethylene. Ring carriers are not typically recycled in Canada and are not accepted by provincial or municipal recycling systems. Ring carriers are a common form of plastic litter (e.g. 1 627 units collected from Canadian shorelines in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup) and are recognized as posing a threat of entanglement for wildlife such as seabirds;

- Stir sticks (also known as stirrers or beverage stirrers). Stir sticks are typically made from polypropylene or polystyrene. They can be in the shape of a stick, rod, or tube, and can also have decorative elements (e.g. for cocktail stir sticks or muddlers) or have attachments to close coffee cup lids. They have very low or no recycling rates and are not typically accepted in provincial or municipal recycling systems. Stir sticks are found as litter in the environment. They are typically categorized alongside straws (e.g. stir sticks would form part of the 26 157 units collected in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup referenced below for straws). Stir sticks pose the same threats to wildlife as straws; and

- Straws. Straws are typically given to customers at restaurants, coffee shops and other food vendors along with purchased drinks. They are typically (but not exclusively) made from polypropylene and have varying physical dimensions. They may also be sold in packages of multiple straws at retail locations such as grocery stores and dollar stores, or may be packaged with another product (e.g. a juice box). Plastic straws are prevalent in litter data (e.g. 26 157 units of straws and stir sticks collected in Canada in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). They have low or nil recycling rates due to their size and shape and are not typically accepted in provincial or municipal recycling systems. Straws are also ranked high by experts in terms of the threat posed to wildlife in the environment.

Several municipal and provincial jurisdictions have already implemented bans on a selection of these six categories of SUPs. For example, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island each implemented bans on SUP checkout bags in 2019 or 2020, which prohibit businesses from offering SUP checkout bags. The bans permit businesses to offer paper and reusable checkout bags, but only Prince Edward Island mandates minimum fees for offering substitute checkout bags. All three of these bans also prohibit “compostable” and oxo-degradable SUP checkout bags and include various exemptions. As of August 2021, no other SUP bans have been enacted at the provincial or territorial level, though British Columbia published a framework to facilitate municipal bans,footnote 12 and a handful of municipal governments have implemented SUP bans on a localized level. For instance, Montréal, Sherbrooke, and several smaller municipalities across Canada have implemented bans on SUP checkout bags, and, while Vancouver has yet to implement a proposed prohibition on SUP checkout bags, a ban on SUP straws, SUP cutlery, and certain SUP foodservice ware came into effect in 2020. Yukon’s May 2021 Speech from the Throne stated that they intend to ban SUPs, but no specifics were provided.

Select Canadian market characteristics

According to the Deloitte Study, Canadian plastic product manufacturing (including SUPs and durable goods) accounted for $25 billion in sales in 2017. Information from Statistics Canada indicates that, in 2017, domestic plastics manufacturers met approximately 50% of domestic demand, while imports met the remaining 50%.footnote 13

Distribution among the six categories of SUPs

As shown in Table 1, the six categories of SUPs accounted for just over $750 million in sales in 2019, or nearly 30 billion units sold. Per capita per day, these values translate to approximately $0.06 in sales and 2.2 units sold. Assuming that each unit sold fulfilled its single use in short order following its sale, the mass of each unit sold promptly became plastic waste. The six categories of SUPs generated approximately 160 000 tonnes of plastic waste in 2019, representing roughly 5% of the total plastic waste generated in Canada in 2019.footnote 14

| Category of SUP table b1 note b | Sales volume (2019, in millions of units) | Average annual growth (2015 to 2019, by volume) | Unit price (2019) | Value (2019, in millions) | Unit weight (grams) | Tonnage (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUP checkout bags | 15 593 | 2.5% | $0.03 | $410 | 8 | 124 746 |

| SUP cutlery | 4 511 | 2.0% | $0.04 | $162 | 2.4 | 10 867 |

| SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics | 805 | 3.2% | $0.09 | $69 | 20.8 | 16 743 |

| SUP ring carriers | 183 | 1.9% | $0.03 | $6 | 3.5 | 648 |

| SUP stir sticks | 2 950 | 3.1% | $0.01 | $29 | 0.6 | 1 770 |

| SUP straws | 5 846 | 2.7% | $0.01 | $77 | 0.4 | 2 339 |

| Total (or weighted average) | 29 888 | 2.5% | $0.03 | $753 | 5.3 | 157 113 |

Table b1 note(s)

|

||||||

Significant progress has been made in recent years by governments and industry globally to phase out several commonly identified SUPs, especially SUP checkout bags, as exemplified by the Global Commitment 2020 Progress Report published by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In Canada, some major companies have announced or have already implemented actions to reduce certain SUPs. For example, certain companies in the quick-service restaurant industry, including A&Wfootnote 15 and Tim Hortons,footnote 16 have already eliminated SUP straws and other SUPs in their Canadian establishments. In 2018, Recipe Unlimited, which operates 19 national restaurant chains such as Swiss Chalet and Harvey’s, committed to eliminating all SUP straws from their restaurants.footnote 17 In the retail space, Canadian grocery chain Sobeys eliminated SUP checkout bags from their stores as of January 2020.footnote 18 Despite these voluntary actions from some Canadian companies to reduce plastic waste in their establishments, consumption of the six categories of SUPs nationally is still projected to grow at a positive rate for the next decade and beyond in the absence of interventions.

Substitutes to the six categories of SUPs

Substitutes to the six categories of SUPs exist, and are readily available within established markets in Canada. Many of these substitutes are single-use manufactured items that are not made from plastics (single-use non-plastic manufactured items, or SUNPs). Most SUNPs are made from paper or wood, and as such, are typically heavier and costlier than their SUP counterparts. Regardless, SUNPs have become more prevalent in the market over time, as consumer preference for a substitute to SUPs is growing as a result of increased awareness of the impacts of plastic waste and plastic pollution. In the case of SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics and SUP ring carriers, substitutes exist that are also plastic manufactured items, but which do not pose the same environmental or value-recovery challenges. The estimated year-over-year market growth for most substitutes to the six categories of SUPs is higher than that of their SUP counterparts. As shown in Table 2, the average annual growth rate from 2015 to 2019 across a selection of readily available single-use substitutes to the six categories of SUPs was 4.7%.

| With respect to which category of SUP | Readily available single-use substitute material | Sales volume (2019, in millions of units) | Average annual growth (2015 to 2019, by volume) | Unit price (2019) | Value (2019, in millions) |

Unit weight (grams) | Tonnage (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUP checkout bags | paper | 3 709 | 4.8% | $0.08 | $279 | 52.6 | 214 562 |

| SUP cutlery | wood | 1 091 | 2.8% | $0.09 | $94 | 1.5 | 1 643 |

| SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics | paper and moulded fibre | 486 | 2.0% | $0.15 | $74 | 38.5 | 18 744 |

| SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics | aluminum | 238 | 0.3% | $0.13 | $32 | 9.5 | 2 262 |

| SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics | recyclable plastics | 148 | -2.7% | $0.12 | $17 | 24 | 3 541 |

| SUP ring carriers | paper and moulded fibre | 127 | 2.7% | $0.29 | $37 | 27.6 | 3 502 |

| SUP ring carriers | recyclable plastics | 53 | 1.6% | $0.14 | $7 | 19.5 | 1 034 |

| SUP ring carriers | plastic film table b2 note b | - | - | $0.10 | - | 18 | - |

| SUP stir sticks | wood | 1 022 | 3.8% | $0.01 | $13 | 1.9 | 1 941 |

| SUP straws | paper | 744 | 13.0% | $0.03 | $20 | 0.8 | 595 |

| Total (or weighted average) | 7 618 | 4.7% | $0.08 | $573 | 30.0 | 247 824 | |

Table b2 note(s)

|

|||||||

Other substitutes to the six categories of SUPs are reusable manufactured items, made from a variety of materials including durable plastics, metals, woods, glass, silicone, and fabrics. Unlike single-use items, reusable items are specifically designed to remain durable through repeated uses and machine washings. Reusable items are heavier and costlier than their SUP or SUNP counterparts, given their durability and associated quantity of raw material needed for their production. However, since a reusable item can be used multiple times, it essentially replaces a stream of single-use items over its useful lifetime. Therefore, the cost of a reusable item will eventually “meet or beat” the total cost of the stream of single-use items it diverted over time. How long it takes to break even depends on the price of the reusable item, the price of the single-use items it diverted, and the rate of reuse.

With respect to the six categories of SUPs, the most commonly used reusable substitute is reusable checkout bags. Many Canadians have shifted their consumer behaviour over time to normalize bringing reusable checkout bags with them when frequenting a variety of retail settings, especially grocery stores, and several of these retail settings themselves sell reusable checkout bags at their checkout counters. Substituting reusable checkout bags for SUP checkout bags is more common in Canada than using substitutes for the five other categories of SUPs. For example, it is not common for consumers to bring their own reusable foodservice ware and reusable cutlery to collect and consume take-out food. Accordingly, reusable items are not seen to play a significant role in diverting the consumption of five of the six categories of SUPs in the short term, relative to the role that SUNP and other single-use substitute items play in that regard. However, education campaigns being conducted by governments and civil society groups are increasing awareness of waste and pollution caused by the consumption of single-use items. Over time, increasing the popularity of low-waste consumer behaviours may lead to more widespread preference for reusable products.

Public opinion research and considerations regarding the COVID-19 pandemic

Survey results suggest that a strong majority of Canadians are concerned about plastic pollution and that they are supportive of further action by governments. In a survey conducted by Abacus Data in 2018, 88% of respondents indicated concern about plastic pollution in oceans and waterways, including 36% who say it is one of the most important environmental issues today.footnote 19 A major polling effort conducted by Ipsos in 2019 surveyed nearly 20 000 adults from 28 countries, showing widespread global support for action on plastics.footnote 20 Across all surveyed countries, 71% of respondents agreed with the statement that single-use plastics should be banned as soon as possible (by country, 72% of Canadian respondents and 57% of American respondents agreed with the statement).

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, public opinion on SUPs bans and consumption patterns towards SUPs is varied. Two surveys conducted by Dalhousie University, one pre-pandemic and another during, depict that support for a ban of all SUP food packaging fell from 72% of respondents in 2019 to 58% of respondents in 2020.footnote 21 Nearly 52% of respondents in 2020 agreed that any new regulations regarding SUP packaging should wait until after the COVID-19 pandemic is fully resolved. The surveys also suggest that consumption habits may have been impacted, as 29% of respondents indicated that they are buying more plastic-packaged goods during the pandemic relative to before the pandemic. Conversely, over 90% of Canadians polled in a recent 2021 survey are concerned about the impact plastic pollution has on our oceans and wildlife and polling by Abacus Data in June 2020 reveals that 86% of Canadians support a ban on some SUPs which is up from 81% in 2019. In an early 2021 survey by Abacus Data commissioned by Oceana Canada, two-thirds of Canadians polled indicated support for extending the proposed prohibitions to cover more than just the six categories of SUPs identified by the Framework, such as cigarette filters, polystyrene and hot and cold drink cups.footnote 22

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the generation of plastic waste in certain fields. Plastics provide protection against the proliferation and spread of bacteria and viruses as the material itself is sanitary and easy to clean. Accordingly, equipment and instruments made of plastics, including SUPs, are often used within the medical field. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, consumption of SUPs within the medical field (among others) has greatly increased, as workers in these settings protect themselves and others through the use of vast amounts of SUP personal protective equipment (PPE), such as masks, face shields, gloves, and gowns, the majority of which are made from petroleum-based, non-biodegradable polymers. In the face of COVID-19, single-use PPE is also attractive for use among the general public due to its sanitary nature.

The Government of Canada is working with provinces to reduce litter and waste from single-use PPE, as usage across all sectors and the general public is expected to continue to increase. The Government of Canada is also investing in Canadian research and technology innovators to develop and commercialize reusable and compostable PPE as well as options for recycling single-use varieties, when possible. While there are some environmental and value-recovery challenges associated with single-use PPE, the Framework in the Discussion Paper does not characterize single-use PPE as “harmful,” given that it serves a vital function that is necessary to keep Canadians safe.

Objective

The objective of the proposed Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations (the proposed Regulations) is to prevent plastic pollution by eliminating or restricting the manufacture, import, and sale of six categories of SUPs that pose a threat to the environment.

Description

The proposed Regulations would eliminate or restrict six categories of SUPs in Canada. The proposed Regulations would be made pursuant to section 93 of CEPA, following the addition of “plastic manufactured items” to Schedule 1 to CEPA.

Applicability

The proposed Regulations would apply to the following categories of plastic items:

- SUP checkout bags, which are plastic manufactured items formed in the shape of a bag that are designed to carry purchased goods from a business, typically given to a customer at the retail point of sale;

- SUP cutlery, which encompasses plastic manufactured items formed in the shape of a knife, fork, spoon, spork, or chopstick;

- SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, which encompasses plastic manufactured items

- formed in the shape of a clamshell container, lidded container, box, cup, plate, or bowl,

- designed for serving or transporting food or beverage that is ready to be consumed without any further preparation, and

- made from or containing the following materials:

- polystyrene foam, including expanded and extruded polystyrene,

- polyvinyl chloride,

- the additive “carbon black,” which is an additive used as a black colour pigment for plastic manufactured items that is produced through the partial or incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons, or

- oxo-degradable plastics, which are plastic materials that include additives which, through oxidation, lead to the fragmentation of the plastic material into micro-fragments or to chemical decomposition;

- SUP ring carriers, which are plastic manufactured items formed in the shape of deformable container-surrounding bands, and that are designed to be applied to beverage containers and selectively severed to produce packages of two or more beverage containers;

- SUP stir sticks, which are plastic manufactured items designed to stir or mix drinks, or to stop a drink from spilling out of a lid; and

- SUP straws, which are plastic manufactured items formed in the shape of a drinking straw, including SUP flexible straws that have a corrugated section that allows the straw to bend and maintain its position at various angles.

The prohibitions in the proposed Regulations would include performance criteria for checkout bags, cutlery, and straws. Plastic checkout bags, plastic cutlery, and plastic straws are only considered single use if they meet the criteria in Table 3. There are no similar criteria for stir sticks, ring carriers, or foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, as all products meeting the definition in the proposed Regulations are expected to be single use.

| Plastic product | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Checkout bag |

|

| Cutlery or straw |

|

Tests to determine whether a product meets the criteria for single-use must be conducted by a laboratory accredited under ISO/IEC 17025 entitled General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories, by an accrediting body that is a signatory to the International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation Mutual Recognition Arrangement. Alternatively, certification can be provided by a lab accredited under the Quebec Environmental Quality Act.

Prohibitions and exceptions

Prohibitions and exceptions for single-use plastic items except plastic straws

The proposed Regulations would prohibit the manufacture, import, and sale of the categories of SUPs described in the previous subsection (with the exception of straws, described in the subsection below). Manufacture, import, and sale for the purposes of export would not be subject to the prohibition.

Prohibitions and exceptions for plastic straws

The proposed Regulations would prohibit the manufacture, import, and sale of SUP straws, including straws packaged with other items such as drink boxes, as well as SUP flexible straws in any commercial, industrial, or institutional setting, except for the following activities:

- the manufacture and import of flexible plastic straws that are sold or offered for sale in packages of multiple straws, where a “flexible” plastic straw has a corrugated section that allows the straw to bend and maintain its position at various angles;

- the manufacture and import of any kind of plastic straw intended for export;

- the sale of flexible plastic straws to hospitals, medical facilities, long-term care facilities, and other care institutions, including the offering of SUP flexible straws to patients or residents of any of these institutions; and

- the sale of packages of 20 or more flexible plastic straws in retail stores, on the condition that the straws are not kept on public display (though businesses may advertise that straws are available for purchase) and are provided only if requested by the customer (who can be any individual).

Record keeping

Any person that manufactures or imports any of the six categories of SUPs for export must keep records providing written evidence that the SUP has been or will be exported. Records and supporting documents must be kept for at least five years after they are made.

Coming into force

The proposed Regulations would come into force one year after their registration, with the exception of prohibitions on sale for checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware made from problematic plastics, ring carriers, and stir sticks, which would come into force two years after registration.

Consequential amendments to other regulations under CEPA

Consequential amendments are needed to the Regulations Designating Regulatory Provisions for Purposes of Enforcement (Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999) [the Designation Regulations], which designate various provisions made pursuant to CEPA as being subject to the fine regime under the Environmental Enforcement Act. Specifically, any regulatory provisions listed in the Schedule to the Designation Regulations are subject to a minimum fine and higher maximum fines, should there be a successful prosecution of an offence involving harm or risk of harm to the environment, or obstruction of authority.footnote 23 Amendments are needed to include the proposed Regulations in the Schedule to the Designation Regulations.

Regulatory development

Consultation

On October 7, 2020, the Department published the Discussion Paper on the CEPA Registryfootnote 24 outlining its proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution. The Discussion Paper was open to a 60-day public comment period from October 7 to December 9. During that period, the Department received written submissions representing the views of 245 stakeholder groups (151 industry members, 39 provincial, territorial, or municipal governments, 2 Indigenous groups, 32 NGOs, and 21 others). In addition, the Department received over 24 000 emails from individual Canadians and an online petition started by a civil society group that received over 100 000 signatures.

The Department also held five webinars and four online stakeholder discussion sessions between October 30 and November 27, 2020. Over 6 000 stakeholders were notified in advance of the webinars, which were also open to the public, with a total participation of 1 474 individuals. For the stakeholder discussion sessions, 100 to 150 stakeholders were invited to each session, with 35 to 50 participants attending each session. Three webinars and three stakeholder discussion sessions addressed the proposed prohibitions on certain SUPs. Topics for discussion included definitions, prohibitions, the potential need for exemptions, and the availability of substitute products. A description of each webinar and stakeholder discussion session, including topics discussed, stakeholder participation, and input received, is available in the What we heard report.

| Row Labels | Oppose | Partially oppose table b4 note a | Partially support table b4 note b | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | 30 | 5 | 10 | 6 |

| Local government | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 |

| Miscellaneous table b4 note c | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| NGO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Provinces and territories | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 33 | 5 | 15 | 46 |

Table b4 note(s)

|

||||

Commenters included industry stakeholders, provincial, territorial, or municipal governments, Indigenous groups, NGOs, and others. Comments covered a range of topics, but generally related to one of seven themes, summarized in the subsections below. Civil society organizations and local governments agreed about the issues plastic pollution is causing for Canadians. Many of these organizations were supportive of a ban on SUPs, though many also urged the Government of Canada to pursue more ambitious measures (e.g. ban additional SUPs). Provincial and territorial governments were mostly supportive of the ban.

Non-conventional plastics

The Discussion Paper included a question about a possible exemption for non-conventional (e.g. oxo-degradable, compostable) plastics.footnote 25 A breakdown of answers by commenter group is below.

| Stakeholder type | Oppose | Partial support | Support | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry | 8 | 7 | 13 | 28 |

| Local government | 12 | 1 | 3 | 16 |

| Miscellaneous table c1 note a | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| NGO | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| Provinces and territories | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Grand total | 28 | 12 | 18 | 58 |

Table c1 note(s)

|

||||

Among industry groups that responded to the question, most supported or partially supported an exemption, citing opportunities for innovation and growth, while continuing to provide options to consumers. In contrast, responses from non-industry stakeholders mostly opposed an exemption, with a minority expressing partial support or support. Commenters giving partial support were often conditional on further action being taken by the Government of Canada, such as establishing standards or consistent definitions for compostable, biodegradable, and bio-based plastics. Opposition to the exemption was mostly linked with concerns about non-conventional plastics contaminating the recycling stream or not composting in the short time frames associated with municipal compost facilities. Local governments, which are typically the operators of compost and recycling facilities, were generally opposed to exemptions on this basis, providing concerns about contamination of compost and recycling streams leading to a lower quality product.

The Department recognizes the potential advantages of using single-use items made from non-conventional plastics in place of counterpart items made from conventional plastics. Some of these benefits include reducing fossil fuel consumption when plant-based materials replace carbon-intensive plastic source materials, and increasing food waste diversion in situations where contamination of plastics may present an obstacle to recycling. The Department also recognizes these benefits are complicated by several issues related to compostable plastics. Some compostable plastics are not accepted in certain compost facilities, leading to their diversion to landfills. In addition, while compostable plastics look very similar to the conventional plastics they replace, many are not designed to be recyclable. This mixing of compostable and conventional plastics can therefore contaminate the recycling stream and reduce recycling recovery rates. Accordingly, the proposed Regulations would treat single-use items made from non-conventional plastics in the same manner as their conventional plastics counterparts. The Department is working with partners and stakeholders, including provinces and territories, to develop the knowledge base about non-conventional plastics, which will inform future actions to promote innovation, clean growth and circularity in this sector.

Accessibility concerns

Some Canadians rely heavily on SUP flexible straws in their day-to-day life, including people with disabilities and those recovering from medical procedures. Many stakeholders requested the Department consider exemptions to any proposed prohibitions on SUP flexible straws to address accessibility concerns. The Department is committed to ensuring that SUP flexible straws remain an option for Canadians who need them. The proposed Regulations would allow Canadians with disabilities to continue to purchase SUP flexible straws for their own use, as well as to access them in hospitals and other medical settings. These accommodations seek to balance the need to ensure accessibility options in Canada while protecting the environment from plastic pollution.

Canada’s international trade commitments

Some stakeholders suggested that banning SUPs may be contrary to the requirements or the spirit of Canada’s international trade commitments. The Government of Canada is aware of its international trade commitments and will continue to respect them. The Department has investigated whether the proposed Regulations could run contrary to Canada’s international trade commitments, and has concluded that they would not. Where required by international agreements, Canada will notify the appropriate parties, such as the World Trade Organization, about the proposed Regulations. All businesses operating in Canada or exporting to Canada would be subject to the proposed prohibitions on certain single-use plastics, removing any unfair advantages within the domestic market. However, the Department is aware of the implications of prohibitions on domestic manufacturers that are competing in the global market, where prohibitions may not be present. Therefore, manufacture of the six categories of SUPs for the purpose of export, as well as import for the purpose of re-export, will continue to be permitted under the proposed Regulations.

Unintended social, economic and environmental effects of substitute products

Some stakeholders expressed concern that wide-ranging bans imposed by government often have unintended consequences, including potential negative social, economic, and environmental effects.

Regarding potential environmental effects, some stakeholders expressed concern that some substitutes to the six categories of SUPs could result in worse environmental impacts. Generally, these concerns included increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions related to transportation of heavier materials (e.g. the mass of single-use paper checkout bags relative to SUP checkout bags) or greater emissions created during the manufacturing process. The Department has carefully analyzed the extent to which substitutes to the six categories of SUPs may lead to harmful environmental impacts. While the proposed Regulations would reduce plastic waste and plastic pollution, some upstream activities such as manufacturing and transportation may have some minor negative environmental impacts. Many of these potential upstream effects can be mitigated through the increased consumption of reusable products, as well as existing management measures that have been put in place by the federal government and other jurisdictions, such as putting a price on carbon pollution, various emissions and effluent regulations for pulp and paper mills and vehicle emissions standards. Greater detail on this subject is available in the “Strategic environmental assessment” section.

Regarding potential social and economic effects, stakeholders noted that some people rely on SUPs to perform crucial functions (e.g. people with disabilities who rely on SUP flexible straws) or because of their relatively low costs. The Department developed the proposed Regulations by taking into account best practices and lessons learned in other jurisdictions and thorough market research to minimize the risk of unintended consequences. In addition, the Department conducted a gender-based analysis plus (GBA+), which analyzed potential impacts of the proposed Regulations on certain demographic groups, including people with disabilities, women, and single parents. The results of this analysis have been incorporated into the regulatory design and implementation strategy (e.g. exemptions for SUP flexible straws), and the Department will work with partners and stakeholders in the implementation of the proposed Regulations to minimize the risk of unintended consequences.

Stakeholders who may have information that could further minimize the risk of environmental, social, or economic unintended consequences are encouraged to contact the Department during the 70-day public comment period.

Economic hardship due to the COVID-19 pandemic

Many stakeholders are concerned that the timing for a ban on certain SUPs is poor, as a result of ongoing economic hardship and stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. While SUP manufacturers and retailers are seeing an increase in sales as a result of COVID-19, these sales are expected to “reset” to approximately 2019 levels once the pandemic has passed.footnote 26 Meanwhile, most other businesses have seen reduced revenues due to forced closures and reduced disposable incomes of consumers. At the same time, almost all businesses are facing increased costs as a result of public health measures (e.g. PPE, hand sanitizer, Plexiglas shields). Additional hardship that may be experienced to source substitutes to the six categories of SUPs comes at a time when many businesses, especially small-to-medium enterprises, may not be able to endure further increases to their cost of business.

The Government of Canada is sensitive to the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the business community and is committed to developing environmental measures in a responsible way and in a manner that also supports economic recovery and the protection of human health. The proposed Regulations take the impacts of the pandemic and other factors, such as accessibility needs, into account. For example, a transition period for the ban of the six categories of SUPs is being proposed to allow businesses to phase out these SUPs with minimal disruption to their operations. Finally, businesses would continue to be allowed to manufacture the six categories of SUPs for the purpose of export.

Ban is not comprehensive enough

Many stakeholders identified other problematic plastics that are of concern to the environment. These stakeholders believe the ban needs to be expanded to include more items.

The Discussion Paper presents the assessment of numerous SUPs to determine if they are environmentally or value-recovery problematic. Items that were selected for the ban have readily available substitutes for consumers to use. At this time, six items were identified as candidates for a potential ban or restriction based on meeting these criteria. Many stakeholders questioned why SUP water bottles were not included in the ban. Water bottles are typically made from polyethylene terephthalate, which is a highly recyclable plastic resin, and are subject to programs such as bottle deposit schemes in many jurisdictions. As a result, they do not meet the criteria for prohibition or restriction under the Framework. Nonetheless, the Department is aware of litter data showing large numbers of SUP bottles in the environment, and will review performance data for existing measures and work with partners and stakeholders to identify areas where further action is needed. More broadly, the Department will continue to monitor the latest research and data relating to plastic pollution in our environment, and will consult with Canadians if additional items are identified to be of concern.

Creation of national standards

Stakeholders requested that the Government of Canada address inconsistencies found in product labelling and advertising when using terms like “recyclable,” “compostable,” and “biodegradable.” Several stakeholders suggested that the creation of national standards for these terms would help consumers better understand the impacts of the products they purchase. These standards might also help Canadians dispose of plastic waste into the proper waste-management stream, thereby reducing contamination issues with recycling and composting facilities.

The creation of national standards are out of scope for the current proposal. While there is currently no regulatory framework in Canada that defines these materials and their management, bio-based plastics standards, including standards for compostable plastic products, will be addressed as part of the Canada-wide Strategy on Zero Plastic Waste.

Modern treaty obligations and Indigenous engagement and consultation

The assessment of modern treaty implications conducted on the proposed Regulations in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation concluded that the proposal would introduce new regulatory requirements on lands covered by modern treaties. However, the proposed regulation is not expected to affect any rights protected under the Constitution Act, 1982 nor those set out in modern treaties.

A survey conducted by the Department of the laws and regulations enacted by Indigenous governments pursuant to modern treaties found that some Indigenous laws and regulations are in place to help manage the impacts of pollution from SUPs. For example

- the Makkovik Inuit Community Government, an Inuit community constituted under the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, has enacted a ban on SUP checkout bags; and

- the Tsawwassen First Nation has enacted the Good Neighbour Regulation that prohibits the littering of plastics, Styrofoam and bags in public places.

Similar to other jurisdictions in Canada that have enacted prohibitions on SUPs or on littering, these measures would be enhanced by federal action to remove certain SUPs from the national market. By doing so, the burden on communities to develop, implement, and enforce local measures will be significantly reduced. Indigenous communities that have enacted measures to address plastic pollution will be informed of the proposed Regulations and invited to provide input.

Through consultations on the Discussion Paper, the Department received written input from two Indigenous organizations: one situated in Northern Quebec, and one situated in Atlantic Canada. These commenters expressed concern with increased levels of plastic pollution in Indigenous communities, explained some of the challenges of managing plastic waste in rural and remote areas, and encouraged the Government of Canada to work closely with communities as it develops measures.

In the spirit of early engagement, the Department held a virtual “face-to-face” meeting with interested Indigenous communities and organizations on January 8, 2021, to discuss the proposed risk management approach presented in the Discussion Paper, answer questions, and solicit feedback. Seven representatives of Indigenous organizations attended the meeting. Input received from this session included the following:

- the Government of Canada should take into consideration the needs of Indigenous communities that may rely on SUPs, such as water bottles and cutlery, during boil-water advisories;

- bans on SUP checkout bags implemented by Indigenous communities have been successful, without significant drawbacks;

- waste management policies, such as extended producer responsibility, are difficult to implement in rural and remote areas, due to the costs of transporting waste; as a result, waste is typically landfilled or burned; and

- further studies should be undertaken to understand the challenges and opportunities for Indigenous communities and businesses to reduce plastic waste and prevent plastic pollution.

In response to input from Indigenous peoples, the Department

- consulted officials at Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, who stated that boil-water advisories should not prevent the washing of reusable cutlery; and

- will continue to seek input from Indigenous peoples on the proposed Regulations. In particular, Indigenous communities that have prohibited or restricted SUPs, or that have put in place other measures to prevent plastic pollution, will be contacted and invited to provide input.

The prepublication comment period is also an opportunity for Indigenous peoples to provide feedback on the proposed Regulations.

Instrument choice

The Prime Minister’s announcement and subsequent Mandate Letter to the Minister of the Environment in 2019, followed by the 2020 Speech from the Throne, set a commitment for the Government of Canada to ban harmful SUPs, where supported and warranted by science. This commitment was reiterated in October 2020 with the publication of the Discussion paper, which described the Government of Canada’s management framework for SUPs. This framework supports the above-mentioned commitment, as well as the Government of Canada’s comprehensive plan to achieve zero plastic waste. It established a three-step process for

- determining the need for particular SUPs to be managed;

- determining the management objective that should be assigned to particular SUPs; and

- choosing the most appropriate instrument to achieve management objectives.

The first step in the framework characterized SUP items as either environmentally problematic, value-recovery problematic, or both, and identified considerations for possible exemptions from management actions. Criteria for categorizing SUP items are described in the table below. Considerations for exemptions from risk management actions included whether a SUP item performs an essential function (e.g. related to accessibility, health and safety, or security) and whether a viable substitute exists that can serve the same function as the SUP item.

| Categories of single-use plastics | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Environmentally problematic |

|

| Value-recovery problematic |

|

The second step in the framework sets three management objectives based on the categorization of SUPs:

- eliminate or significantly reduce SUPs entering Canada’s environment;

- reduce the environmental impact of plastic products overall; and

- conserve material resources by increasing the value recovery of plastics.

The third step of the framework was to select policy instruments informed by the Department’s Instrument Choice Framework for Risk Management under CEPA. Under this framework, instruments are chosen based on several criteria, including the following:

- environmental effectiveness and achievement of the management objective;

- maximization of benefits and minimization of costs;

- distributional impacts on groups and segments of society;

- stakeholder acceptability and compatibility with other programs in Canadian jurisdictions; and

- meeting international obligations, including international protocols, agreements, and trade obligations.

Potential instruments identified under the framework include bans and restrictions on use, incentives to encourage the use of reusable products or systems, material specifications (e.g. recyclability rules or guidelines), and extended producer responsibility or other collection and recycling requirements.

The Department assessed fourteen categories of SUPs according to the criteria in the management framework described in the Discussion Paper. A total of six categories of SUPs met the criteria outlined in the first step of the framework for being both environmentally and value-recovery problematic, and therefore were identified as candidates for a ban or restrictions on their use. The other eight categories of SUPs that did not meet all the criteria are potential candidates for management using other instruments. For example, the Department identified material specifications as the most appropriate instrument for multi-material packaging. The Department will continue to consult and work with jurisdictions, stakeholders and the public to help determine how these other SUPs can be better managed to reduce plastic pollution and improve value recovery.

Under the framework, regulatory actions banning or restricting SUPs that are both environmentally and value-recovery problematic was identified as the only viable option to eliminate, or significantly reduce these SUPs entering Canada’s environment. The Department identified the development of regulations under section 93 of CEPA, following the addition of plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1 to the Act, as the preferred risk-management approach, given that CEPA is one of the Government of Canada’s key pieces of legislation to prevent pollution that can cause environmental harm. The Act also provides a broad suite of tools that allow for flexibility to tailor measures to the specific issues requiring action.

Regulatory analysis

Benefits and costs

Analytical framework

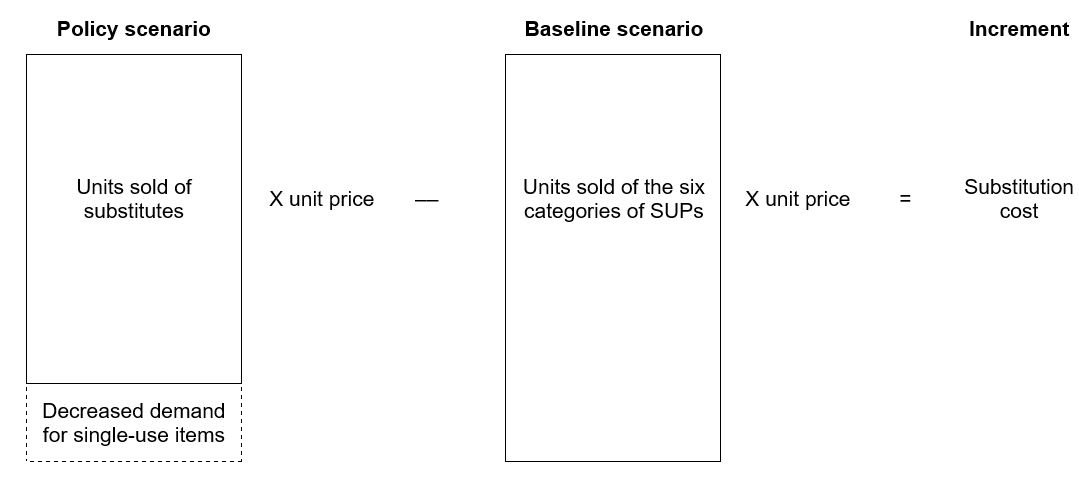

In order to analyze the incremental impacts of the proposed Regulations, the Department developed an analytical framework to characterize the costs and benefits (Figure 2). Unless otherwise stated, all costs and benefits in the following subsections are presented in 2020 Canadian dollars, present value to base year 2021 using a 3% discount rate. The social discount rate of 3% is applied in the central analysis since the proposed Regulations would primarily affect private consumption of goods and services. Total monetized benefits and costs discounted at 7%, as well as non-discounted totals, are presented in the “Sensitivity analysis” subsection of the “Benefits and costs” section.

| Policy design and activities | Costs | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

Prohibition on six categories of SUPs, resulting in

|

Economic costs:

|

|

| Record keeping | Administrative costs | N/A |

| Compliance promotion | Government costs | N/A |

| Enforcement activities | Government costs | N/A |

The policy design and activities depicted in the analytical framework correspond to those presented in the “Description” section. Before any costs or benefits can be estimated, the impact of the proposed Regulations on plastic waste and plastic pollution must first be quantified.

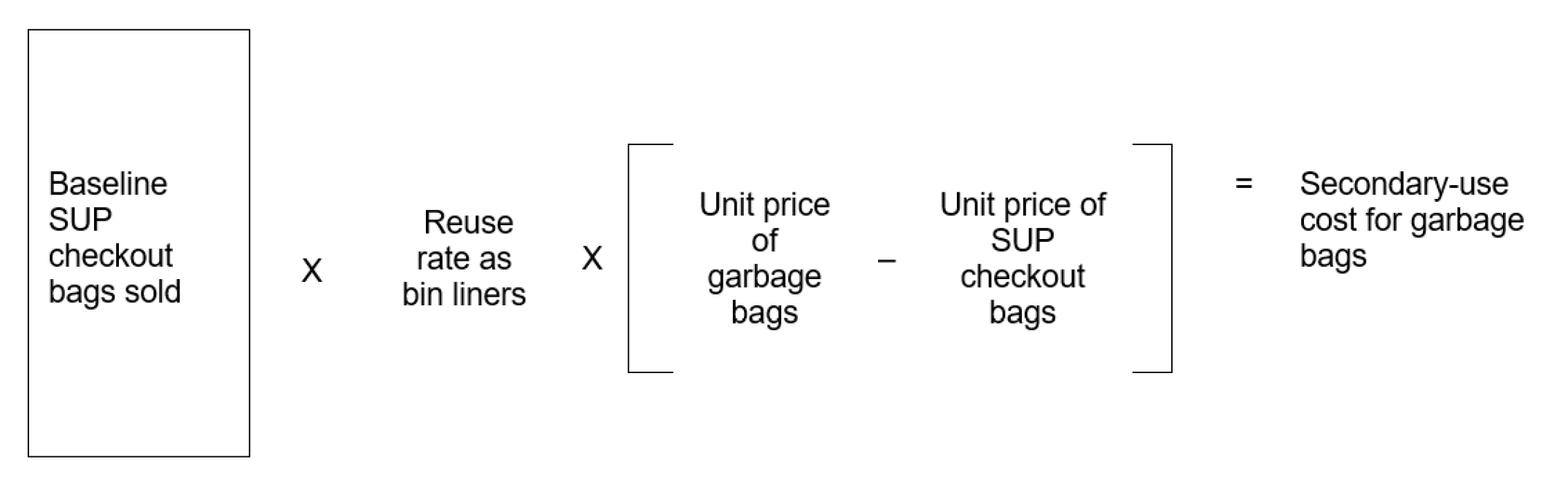

Quantifying the decrease in plastic waste (and associated increase in waste from substitutes)

Since single-use manufactured items are designed to become waste immediately after their single-use function has been fulfilled, the analysis assumes that “units sold” is equivalent to “waste generated.” In order to quantify the change in waste associated with the proposed Regulations, the sales volumes over time for the six categories of SUPs and their main substitutes can be estimated, first in absence of the Regulations (baseline scenario), and then, given the Regulations (policy scenario). A quantification framework for this estimation is presented in Figure 3, where the area of each rectangle represents the sales volume of a given SUP and its main substitutes (note: areas are not to scale, diagram is illustrative only).

Figure 3. Quantification framework for units sold / waste generated in Canada

Figure 3. Quantification framework for units sold / waste generated in Canada - Text version

In the cost-benefit analysis, each unit sold of the six categories of SUPs in the baseline scenario is reallocated into one of three following pathways in the policy scenario: exemptions, behaviour change, or prohibitions. The baseline quantity in the Canadian marketplace of the six categories of SUPs exempted would remain constant in the policy scenario, while the baseline quantity of the six categories of SUPs prohibited would be replaced by readily available substitutes in the policy scenario. A portion of the baseline quantity of the six categories of SUPs in the marketplace would be subject to behaviour change that reduces demand for single-use items altogether. Accordingly, the overall quantity of single-use items sold in the policy scenario would be somewhat less than that in the baseline scenario.

The quantifications following the framework in Figure 3 are presented in the subsections below.

Baseline scenario

The Department acquired off-the-shelf market data on checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware, ring carriers, stir sticks and straws from international data analytics firms, and cross-referenced this data against other research (e.g. the Statistics Canada Supply and Use Tables, proprietary information from industry, publicly available literature, and manufacturer, distributor, or wholesaler websites) to create a historical database spanning from 2015 to 2019. The database includes estimates for sales volume, average price per unit (as paid by the final retailer), and the average mass per unit across the six categories of SUPs and their main substitutes. Sales volume is multiplied by average price per unit to estimate market value and by average mass per unit to estimate tonnage. These estimates for 2019 are presented in Table 1 and Table 2 in the “Background” section.

In order to construct a projected baseline scenario, the average annual growth in sales volumes over the historical period (2015 to 2019) for the six categories of SUPs and their main substitutes are first calculated and then applied from 2024 onward. The analysis assumes no sales growth for the six categories of SUPs and their main substitutes between 2019 and 2023 to account for the high level of uncertainty related to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on these markets. In the midst of public health measures such as stay-at-home orders, temporary business closures and teleworking, the use patterns of Canadians with respect to the six categories of SUPs have changed. For instance, greater uptake in take-out meals may contribute to higher usage of foodservice ware and cutlery, while fewer social outings in restaurants and bars may contribute to lower usage of straws and stir sticks. There is great uncertainty as to what the lasting market impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the six categories of SUPs may be. Equating projected sales volumes in 2023 with those observed in 2019 assumes that the markets for these goods will not shift permanently onto a different course, but rather, that they will “reset” back to their former usage rates and observed growth patterns once public health restrictions ease.

The projected baseline also takes into account Canadian jurisdictions that have implemented localized bans on any of the six categories of SUPs that have come into force after 2019 and prior to June 2021 (e.g. Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Vancouver, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Sherbrooke), by adjusting the projected baseline sales volumes downward proportionate to the percentage of the population living in areas covered by these bans. This is to ensure that the costs and benefits of measures undertaken by other jurisdictions are not attributed to the proposed Regulations. The projected baseline does not take into account any announcements from governments or industry regarding future intent to phase out usage of any of the six categories of SUPs, as these announcements are non-binding.

Policy scenario

As illustrated in Figure 3, all sales of the six categories of SUPs in the baseline scenario would be reallocated into one of three outcomes in the policy scenario: exemptions, demand reduction, or substitution. The reallocation factors into each outcome used in the analysis are presented in Table 7.