Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations: SOR/2019-353

Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 153, Number 26

Registration

SOR/2019-353 December 19, 2019

TOBACCO AND VAPING PRODUCTS ACT

CANADA CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY ACT

P.C. 2019-1416 December 18, 2019

Her Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of Health, makes the annexed Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations pursuant to

- (a) sections 17 footnote a and 33 footnote b of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act footnote c; and

- (b) section 37 footnote d of the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act footnote e.

TABLE OF PROVISIONS

Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations

PART 1

Labelling — Awareness of Health Hazards from Use of Vaping Products

Interpretation

1 Definitions

Application

2 Retail sale — vaping products

3 Non-application

Purpose

4 Labelling — Tobacco and Vaping Products Act

Vaping Products Containing Nicotine

Nicotine Concentration Statement

5 Requirement — vaping product containing nicotine

6 Requirement — nicotine concentration

7 Placement — vaping device and vaping part

8 Placement — packaged vaping device and vaping part

9 Placement — refill vaping product

10 Placement — vaping products in kit

11 Placement — kit

12 Placement — prepackaged product

Health Warning

13 Requirement — vaping product containing nicotine

14 List of health warnings

15 Amended health warning

16 Placement — vaping device and vaping part

17 Placement — packaged vaping device and vaping part

18 Placement — refill vaping product

19 Placement — vaping products in kit

20 Placement — kit

21 Attribution

Vaping Products Without Nicotine

22 No nicotine

23 Permitted expressions

24 Placement

Presentation of Information

Official Languages

25 Required health warning and permitted expression

Technical Specifications

General

26 Integrity

27 Permanence

28 Legibility

29 Characters in text

30 Visibility

Nicotine Concentration Statement

31 Specific legibility rules

Health Warning

32 Text — health warning

33 Official languages — placement

34 Official languages — vaping product and package

35 Visibility

36 Specific legibility rules

Leaflet and Tag

37 Display of information

38 Specific legibility rule

39 Leaflet

40 Tag — visibility

41 Tag — safe handling

Attribution

42 Continuous text

PART 2

Labelling and Packaging — Protection of Human Health or Safety

Interpretation

43 Definitions

Application

44 Vaping products — consumer products

Purpose

45 Requirements — Canada Consumer Product Safety Act

Exception

46 Importation to bring into compliance or to export

Requirements

List of Ingredients

47 Contents

48 List of ingredients — placement

49 Maximum nicotine concentration

Child-Resistant Containers

50 Requirement — child-resistant container

51 Applicable standard

52 Maintain characteristics

53 Evaluation

54 Documents

55 Directions for opening and closing

56 Single-use immediate container

57 Toxicity information

58 Vaping device and vaping part

Presentation of Information

59 Languages, legibility and durability

60 Information in words — general rules

61 Order of presentation of ingredients

62 Directions to open and close

63 Hazard symbol — minimum diameter

64 Toxicity warning and first aid treatment statement

PART 3

Transitional Provision, Related Amendment and Coming into Force

Transitional Provision

65 Toxicity information

Related Amendment

Canada Consumer Product Safety Act

66 Consumer Chemicals and Containers Regulations, 2001

Coming into Force

67 July 1, 2020

SCHEDULE 1

SCHEDULE 2

Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations

PART 1

Labelling — Awareness of Health Hazards from Use of Vaping Products

Interpretation

Definitions

1 (1) The following definitions apply in this Part.

- display surface means the portion of the surface area of a vaping product or package on which the information referred to in this Part can be displayed. It does not include the surface area of the bottom, of any seam or of any concave or convex surface near the top or the bottom of a vaping product or package. (aire d’affichage)

- exterior package means a package that contains a vaping product and that is displayed or visible under normal or customary conditions of sale or use of the vaping product. (emballage extérieur)

- interior package means the innermost package of a vaping product, including a blister pack. (emballage intérieur)

- kit means a package that contains a collection of two or more units of vaping products. (trousse)

- main display panel means, in respect of a vaping product or package, the part of the display surface that is displayed or visible under normal or customary conditions of sale or use of the vaping product. It includes

- (a) in the case of a vaping product or package that has a rectangular cuboid shape, one of the largest sides of the display surface;

- (b) in the case of a vaping product or package that has a cylindrical shape, the larger of

- (i) the area of the top, or

- (ii) 40% of the area obtained by multiplying the circumference of the vaping product or package by the height of the display surface;

- (c) in the case of a bag, the largest side of the bag; and

- (d) in any other case, the largest surface of the vaping product or package that is not less than 40% of the display surface. (aire d’affichage principale)

- manufacturer does not include an individual or entity that only packages or labels vaping products on behalf of a manufacturer. (fabricant)

- vaping device has the meaning assigned by paragraphs (a) and (b) of the definition vaping product in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. (dispositif de vapotage)

- vaping part has the meaning assigned by paragraph (c) of the definition vaping product in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. (pièce de vapotage)

- vaping substance has the meaning assigned by paragraph (d) of the definition vaping product in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. (substance de vapotage)

Interpretation — package

(2) In this Part, a reference to an exterior package or interior package does not include package liners or shipping containers or any outer wrapping, including a box, that is not displayed or visible under normal or customary conditions of sale or use of a vaping product.

Interpretation — refill vaping product

(3) In this Part, a reference to a vaping product that is intended to be used for the purpose of refilling another vaping product does not include a reference to a vaping device or vaping part.

Application of meanings in Tobacco and Vaping Products Act

(4) All other words and expressions used in this Part have the same meaning as in the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act.

Application

Retail sale — vaping products

2 (1) This Part applies to every vaping product that is intended for retail sale in Canada, as well as to its packaging.

Other means of furnishing — vaping products

(2) This Part also applies to every vaping product that is intended to be furnished by any means other than retail sale, as well as to its packaging.

Non-application

3 This Part does not apply to vaping products that are subject to the Food and Drugs Act.

Purpose

Labelling — Tobacco and Vaping Products Act

4 (1) For the purposes of sections 15.1 and 15.2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act, this Part sets out the labelling requirements that manufacturers of vaping products must meet

- (a) in respect of information that is required to be displayed about vaping products and their emissions and about the health hazards and health effects arising from the use of those products and from their emissions; and

- (b) in respect of the manner of displaying the information referred to in paragraph (a) on vaping products and their packages, as well as on leaflets and on any tags attached to vaping products.

Permitted expressions

(2) For the purposes of sections 30.42 and 30.45 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act, this Part also sets out the requirements that manufacturers of vaping products must meet in respect of the manner of displaying certain non-mandatory expressions on vaping products and their packages.

Vaping Products Containing Nicotine

Nicotine Concentration Statement

Requirement — vaping product containing nicotine

5 Every vaping product that contains nicotine must display a nicotine concentration statement.

Requirement — nicotine concentration

6 The nicotine concentration statement must set out the concentration of nicotine in the vaping substance, expressed in milligrams per millilitre. The concentration must be preceded by “Nicotine — ” and followed by the unit of measure “mg/mL”.

Placement — vaping device and vaping part

7 The nicotine concentration statement must be displayed, in the case of a vaping device or vaping part that is not packaged, on the main display panel or on a tag.

Placement — packaged vaping device and vaping part

8 (1) The nicotine concentration statement must be displayed, in the case of a vaping device or vaping part that is packaged, on the main display panel of the exterior package.

Multiple layers of packaging

(2) If a vaping device or vaping part is packaged in multiple layers of packaging, the nicotine concentration statement must also be displayed on

- (a) the main display panel of the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be; or

- (b) the main display panel of the interior package.

Placement — refill vaping product

9 (1) The nicotine concentration statement must be displayed, in the case of a vaping product that is intended to be used for the purpose of refilling another vaping product, on the main display panel of that refill vaping product.

Placement — packaged refill vaping product

(2) If the refill vaping product is packaged, the nicotine concentration statement must also be displayed on the main display panel of the exterior package.

Placement — vaping products in kit

10 (1) The nicotine concentration statement must be displayed, in the case of a vaping device or vaping part that is packaged in a kit, on

- (a) the main display panel of the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be;

- (b) the main display panel of the interior package of the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be; or

- (c) a tag.

Kit — refill vaping product

(2) The nicotine concentration statement must be displayed, in the case of a vaping product that is intended to be used for the purpose of refilling another vaping product and that is packaged in a kit, on the main display panel of that refill vaping product.

Placement — kit

11 (1) If vaping products that contain nicotine are packaged in a kit, the nicotine concentration statement that is required for each of those vaping products must be displayed on the main display panel of the kit.

One nicotine concentration statement

(2) However, if two or more of the vaping products in the kit have the same concentration of nicotine, the nicotine concentration statement that is applicable to those vaping products must be displayed only once on the main display panel of the kit.

Placement — prepackaged product

12 If a vaping product is a prepackaged product, as defined in subsection 2(1) of the Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act, and its identity is shown, as required under subparagraph 10(b)(ii) of that Act, in terms of its common or generic name or in terms of its function, the nicotine concentration statement must be displayed immediately below that name or function.

Health Warning

Requirement — vaping product containing nicotine

13 Every vaping product that contains nicotine must display a health warning.

List of health warnings

14 The health warning that is required for a vaping product is the health warning set out for that vaping product in the document entitled List of Health Warnings for Vaping Products, as amended from time to time and published by the Government of Canada on its website.

Amended health warning

15 Despite these Regulations, if a person has displayed, in accordance with this Part, a health warning that is set out in the List of Health Warnings for Vaping Products, as the list read immediately before the day on which the amended version of that list is published by the Government of Canada, the person may continue to so display that health warning during the period of 180 days after the day on which the amended list is published.

Placement — vaping device and vaping part

16 The health warning must be displayed, in the case of a vaping device or vaping part that is not packaged, on the main display panel or on a tag.

Placement — packaged vaping device and vaping part

17 (1) The health warning must be displayed, in the case of a vaping device or vaping part that is packaged, on the main display panel of the exterior package.

Exception — small exterior package

(2) However, if the main display panel of the exterior package has an area of less than 15 cm2, the health warning may be displayed elsewhere on the display surface of the exterior package or in a leaflet.

Multiple layers of packaging

(3) If a vaping device or vaping part is packaged in multiple layers of packaging, the health warning must also be displayed

- (a) if the main display panel of the interior package has an area of at least 15 cm2,

- (i) on the main display panel of the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be, or

- (ii) on the main display panel of the interior package; and

- (b) if the main display panel of the interior package has an area of less than 15 cm2,

- (i) elsewhere on the display surface of the interior package, or

- (ii) in a leaflet.

Placement — refill vaping product

18 (1) The health warning must be displayed, in the case of a vaping product that is intended to be used for the purpose of refilling another vaping product, on the main display panel of that refill vaping product.

Exception — small refill vaping product

(2) However, if the main display panel of the refill vaping product has an area of less than 15 cm2, the health warning may be displayed on a tag.

Placement — packaged refill vaping product

(3) If the refill vaping product is packaged, the health warning must also be displayed on the main display panel of the exterior package.

Placement — vaping products in kit

19 (1) The health warning must be displayed, in the case of a vaping device or vaping part that is packaged in a kit, on

- (a) the main display panel of the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be;

- (b) the main display panel of the interior package of the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be; or

- (c) a tag.

Kit — refill vaping product

(2) The health warning must be displayed, in the case of a vaping product that is intended to be used for the purpose of refilling another vaping product and that is packaged in a kit, on

- (a) the main display panel of that refill vaping product; or

- (b) if the main display panel of the refill vaping product has an area of less than 15 cm2,

- (i) the main display panel of the interior package of a refill vaping product that is packaged, or

- (ii) a tag.

Placement — kit

20 (1) If a vaping product that contains nicotine is packaged in a kit, the health warning that is required for that vaping product must be displayed on the main display panel of the kit.

One health warning — kit

(2) However, if two or more of the vaping products in the kit contain nicotine, the required health warning need only be displayed once on the main display panel of the kit.

Attribution

21 If a manufacturer attributes a health warning, the manufacturer must do so by displaying the phrase “Health Canada” immediately beside or below the English version of the health warning and the phrase “Santé Canada” immediately beside or below the French version of the health warning.

Vaping Products Without Nicotine

No nicotine

22 A vaping product may display an expression permitted by section 23 if

- (a) in the case of a vaping substance, it does not contain nicotine; and

- (b) in the case of any other vaping product that contains a vaping substance, the product does not contain nicotine.

Permitted expressions

23 Only one of the following expressions is permitted to be displayed on a vaping product:

- (a) “Nicotine-free” in the English version of the expression and “Sans nicotine” in the French version of the expression;

- (b) “No nicotine” in the English version of the expression and “Aucune nicotine” in the French version of the expression; or

- (c) “Does not contain nicotine” in the English version of the expression and “Ne contient pas de nicotine” in the French version of the expression.

Placement

24 An expression permitted by section 23 must be displayed only on the display surface of a vaping product or of any package containing the vaping product.

Presentation of Information

Official Languages

Required health warning and permitted expression

25 The required health warning and any expression permitted by section 23 must be displayed in both official languages, in the same manner.

Technical Specifications

General

Integrity

26 (1) The customary method of opening a vaping product or package must not sever, otherwise damage or render illegible any letter, word or part of the required information or of an expression permitted by section 23.

Exception — blister pack

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply to an interior package that is a blister pack.

Permanence

27 Any required information and any expression permitted by section 23 must be irremovable.

Legibility

28 (1) Any required information must

- (a) be displayed in a standard sans-serif type that

- (i) is not compressed, expanded or decorative,

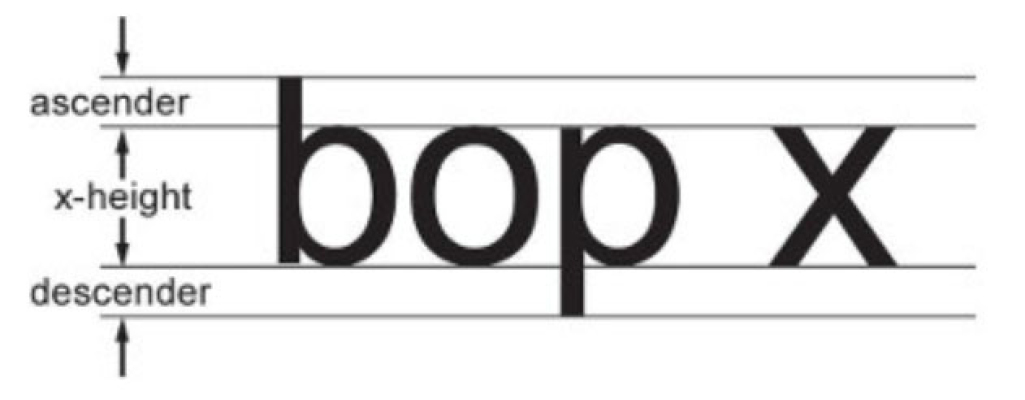

- (ii) is black on a white background, and

- (iii) as illustrated in Schedule 2, has a large x-height relative to the ascender or descender of the type; and

- (b) be clear and legible and remain so throughout the useful life of the vaping product, under normal or customary conditions of transportation, storage, sale and use.

Measurement of height of type

(2) The height of the type must be determined by measuring an upper case letter or a lower case letter that has an ascender or a descender, such as “b” or “p”.

Characters in text

29 Each character in the text of the required information must have the same font and type size.

Visibility

30 Any required information must not be concealed or obscured by any other information that is required or permitted to be displayed under the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act, any other Act of Parliament or any Act of the legislature of a province.

Nicotine Concentration Statement

Specific legibility rules

31 (1) A nicotine concentration statement that is displayed on a vaping product or package must be displayed

- (a) in a type that has a minimum height of 3 mm and a minimum body size of 8 points, if the main display panel has an area equal to or greater than 45 cm2;

- (b) in a type that has a minimum height of 2 mm and a minimum body size of 6 points, if the main display panel has an area equal to or greater than 10 cm2 but less than 45 cm2; and

- (c) in a type that has a minimum height of 1.5 mm and a minimum body size of 4.5 points, if the main display panel has an area of less than 10 cm2.

Measurement of height of type

(2) The height of the type must be determined in accordance with subsection 28(2).

Health Warning

Text — health warning

32 A health warning must be displayed in such a manner that

- (a) the first word is in upper case letters and bold type;

- (b) the remaining text is not in bold type and is in sentence case letters.

Official languages — placement

33 A health warning in one official language must be displayed immediately beside or below the health warning in the other official language and the two must not be combined.

Official languages — vaping product and package

34 In the case of a vaping product or package, the health warning in both official languages must be displayed on the same main display panel or display surface, as the case may be.

Visibility

35 A health warning that is displayed on a vaping product or package must

- (a) in the case of a vaping product or package that is cylindrical in shape, not extend beyond the main display panel;

- (b) in the case of a vaping product or package that has a rectangular cuboid shape, be displayed on the main display panel; and

- (c) in the case of a bag or any other package, be readable in its entirety under normal or customary conditions of sale or use of the vaping product, without further manipulation of the bag or package.

Specific legibility rules

36 (1) In the case of a health warning that is displayed on a vaping product or package, the health warning must be displayed

- (a) in a type that has a minimum height of 2 mm and a minimum body size of 6 points, if the main display panel has an area of less than 45 cm2; and

- (b) in a type that has a height and body size that results in the health warning in both official languages occupying not less than 35% of the main display panel, if the main display has an area equal to or greater than 45 cm2.

Measurement of height of type

(2) The height of the type must be determined in accordance with subsection 28(2).

Leaflet and Tag

Display of information

37 Any required information that is displayed in a leaflet or on a tag must be

- (a) positioned as close as possible to the top edge of the surface of the leaflet or tag, in such a manner that, if applicable, any nicotine concentration statement is immediately above the health warning; and

- (b) displayed in such a manner that it is readable in its entirety under normal or customary conditions of sale or use of the vaping product, without further manipulation of the leaflet or tag.

Specific legibility rule

38 (1) Any required information that is displayed in a leaflet or on a tag must be displayed in a type that has a minimum height of 2 mm and a minimum body size of 6 points.

Measurement of height of type

(2) The height of the type must be determined in accordance with subsection 28(2).

Leaflet

39 A leaflet that displays a health warning that is required for a vaping product must be inserted in the package containing the vaping product.

Tag — visibility

40 A tag must not conceal or obscure any required information that is displayed on the vaping product or its package under the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act, any other Act of Parliament or any Act of the legislature of a province.

Tag — safe handling

41 A tag must not interfere with the normal use or safe handling of the vaping product.

Attribution

Continuous text

42 (1) The attribution of a health warning must be displayed in such a manner that there is no intervening image or text between the attribution and the health warning.

Specific legibility rules

(2) The attribution of a health warning must be displayed in such a manner that

- (a) it meets the requirements set out in sections 28 and 29;

- (b) it is not in bold type; and

- (c) the height and body size of the type of the attribution are no larger than those of the type of the health warning.

Characters in text

(3) Each character in the text of the attribution must have the same font as the text of the health warning.

PART 2

Labelling and Packaging — Protection of Human Health or Safety

Interpretation

Definitions

43 (1) The following definitions apply in this Part.

- display surface means the portion of the surface area of an immediate container or of an exterior package on which the information referred to in this Part can be displayed. It does not include the surface area of the bottom, of any seam or of any concave or convex surface near the top or the bottom of the immediate container or exterior package. (aire d’affichage)

- exterior package means a package, other than an immediate container, that contains a vaping product and that is displayed or visible under normal or customary conditions of sale of the vaping product to a consumer. (emballage extérieur)

- hazard symbol means the pictograph and its frame as set out in Schedule 1. (pictogramme de danger)

- immediate container means the container, including a vaping device or vaping part, that is in direct contact with a vaping substance or which it is reasonably foreseeable will be in direct contact with such a substance. (contenant immédiat).

- main display panel means the part of the display surface that is displayed or visible under normal or customary conditions of sale to the consumer. It includes

- (a) in the case of a rectangular immediate container or exterior package, the largest side of the display surface;

- (b) in the case of a cylindrical immediate container or exterior package, the larger of

- (i) the area of the top, or

- (ii) 40% of the area obtained by multiplying the circumference of the immediate container or exterior package by the height of the display surface;

- (c) in the case of a bag, the largest side of the bag; and

- (d) in any other case, the largest surface of the immediate container or exterior package, as the case may be, that is not less than 40% of the display surface. (aire d’affichage principale)

- responsible person means

- (a) the manufacturer that, in Canada, manufactures a vaping device or vaping part or places a vaping substance in its immediate container; and

- (b) the importer, in the case of a vaping device or vaping part that is imported or a vaping substance that is imported in its immediate container. (responsable)

- vaping device has the meaning assigned by paragraphs (a) and (b) of the definition vaping product in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. (dispositif de vapotage)

- vaping part has the meaning assigned by paragraph (c) of the definition vaping product in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. (pièce de vapotage)

- vaping product has the same meaning as in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. (produit de vapotage)

- vaping substance has the meaning assigned by paragraph (d) of the definition vaping product in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. (substance de vapotage)

Interpretation of “should”

(2) If the word “should” is used in a standard that is referred to in this Part it is to be read as imperative, unless the context requires otherwise.

Application of meanings in Canada Consumer Product Safety Act

(3) All other words and expressions used in this Part have the same meaning as in the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act.

Application

Vaping products — consumer products

44 (1) This Part applies to vaping products that are consumer products.

Non-application

(2) For greater certainty, this Part does not apply to vaping products that are subject to the Food and Drugs Act.

Purpose

Requirements — Canada Consumer Product Safety Act

45 For the purposes of section 6 of the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act, this Part sets out requirements that must be met by vaping products that are consumer products.

Exception

Importation to bring into compliance or to export

46 (1) A person may import a vaping product that does not comply with a requirement of this Part for the purpose of

- (a) bringing the product into compliance with the requirement;

- (b) reselling the product to a manufacturer in Canada that will bring it into compliance with the requirement; or

- (c) exporting the product to another country.

Credible evidence

(2) A person that imports a vaping product for a purpose described in subsection (1) must, on the request of an inspector, provide credible evidence to the inspector that it is being brought into compliance or is being exported.

Requirements

List of Ingredients

Contents

47 (1) A list of ingredients is required for every vaping substance and must set out the common name, without abbreviation, of each ingredient that is present in the vaping substance. The list must begin with the title “Ingredients:” in the English version of the list and the title “Ingrédients :” in the French version of the list.

List of ingredients — “flavour”

(2) If any ingredients or combination of ingredients are added to a vaping substance solely to produce a particular flavour or combination of flavours, instead of being denoted in the list of ingredients by their common names, those ingredients must be denoted by the indication “flavour” in the English version of the list and “arôme” in the French version of the list.

List of ingredients — placement

48 (1) Subject to subsections (2) and (3), the list of ingredients must be displayed on the display surface of the immediate container of the vaping substance and on the display surface of any exterior package.

Exception — vaping device and vaping part

(2) If the immediate container is a vaping device or vaping part and it is not packaged, the list of ingredients must be displayed on a tag attached to the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be.

Exception — size of main display panel

(3) If the main display panel of the immediate container has an area of less than 45 cm2, the list of ingredients must be displayed on the display surface of the exterior package or a tag attached to the immediate container.

Maximum nicotine concentration

49 A vaping product must not contain nicotine in a concentration of 66 mg/mL or more.

Child-Resistant Containers

Requirement — child-resistant container

50 (1) Every immediate container that is a vaping device or vaping part, as well as every other immediate container that contains a vaping substance that has a nicotine concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more, must meet the requirements set out in section 51 for a child-resistant container.

Exception

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply if exposure to a vaping substance that is in a form other than an aerosol is impossible during the reasonably foreseeable use of the container.

Applicable standard

51 (1) A child-resistant container must

- (a) be constructed so that it can be opened only by operating, puncturing or removing one of its functional and necessary parts using a tool that is not supplied with the container; or

- (b) meet the child test protocol requirements of one of the following standards or a standard that is at least equivalent:

- (i) the Canadian Standards Association Standard CAN/CSA Z76.1-16, entitled Reclosable child-resistant packages, as amended from time to time,

- (ii) the International Organization for Standardization Standard ISO 8317:2015, entitled Child-resistant packaging — Requirements and testing procedures for reclosable packages, as amended from time to time, or

- (iii) the United States Code of Federal Regulations, Title 16: Commercial Practices, section 1700.20, entitled “Testing procedure for special packaging”, as amended from time to time.

Amended standard

(2) Despite paragraph (1)(b), if a person has applied the child test protocol requirements of one of the standards referred to in that paragraph to a child-resistant container, as the standard read immediately before the day on which an amended version of that standard is published, the person may continue to apply those requirements to the child-resistant container during the period of 180 days after the day on which the amended standard is published.

Maintain characteristics

52 A child-resistant container must maintain the characteristics of a child-resistant container throughout the useful life of the vaping substance that is placed in it, or in the case of a refillable container, throughout its useful life, under normal conditions of storage, sale and use.

Evaluation

53 (1) The responsible person, using good scientific practices, must evaluate

- (a) the compatibility of the vaping substance with its child-resistant container to determine that the chemical or physical properties of the substance will not compromise or interfere with the proper functioning of the container; and

- (b) the physical wear and stress factors and the force required for opening and closing the container to determine that the proper functioning of the container will be maintained for the number of openings and closings reasonably foreseeable for the size and contents of the container.

Definitions

(2) The following definitions apply in this section.

- good scientific practices means

- (a) for the development of test data, conditions and procedures that are in accordance with or equivalent to those set out in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development document entitled OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, as amended from time to time;

- (b) for laboratory practices, practices that are in accordance with the principles set out in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development document entitled OECD Principles of Good Laboratory Practice, Number 1 of the OECD Series on Principles of Good Laboratory Practice and Compliance Monitoring, as amended from time to time; and

- (c) for human experience data, a peer-reviewed study of clinical cases. (bonnes pratiques scientifiques)

- human experience data means data, collected in accordance with good scientific practices, that demonstrates that injury to or poisoning of a human has or has not resulted from

- (a) exposure to a vaping substance; or

- (b) the reasonably foreseeable use of a vaping substance or immediate container by a consumer, including by a child. (données de l’expérience humaine)

Documents

54 (1) The responsible person must prepare and maintain documents containing the following information and must keep those documents for a period of at least three years after the day on which the child-resistant container is manufactured or imported:

- (a) the specifications critical to the child-resistant characteristics of the container, including

- (i) the physical measurements within which the container retains its child-resistant characteristics,

- (ii) if applicable, the torque that must be applied to open or close the container, and

- (iii) the compatibility of the container and its closure system with the vaping substance that is to be placed into it; and

- (b) the test results that demonstrate that the container and its closure system meet the requirements of a standard referred to in paragraph 51(1)(b).

Inspector’s request

(2) In the case of a vaping substance for which a child-resistant container is required, the responsible person must provide an inspector with any of the documents that the inspector requests within 15 days after the day on which the request is received.

Directions for opening and closing

55 (1) Directions for opening and, if applicable, closing a child-resistant container that meets the requirements of paragraph 51(1)(b) must be displayed on the closure system of the immediate container or on the display surface of the immediate container.

Exception — vaping device and vaping part

(2) However, in the case of an immediate container that is a vaping device or vaping part, the directions may be displayed

- (a) on a package containing the vaping device or vaping part, or on a leaflet that is inserted in the package; or

- (b) if it is not packaged, on a tag that is attached to the vaping device or vaping part.

Single-use immediate container

56 (1) Subject to subsections (3) and (5), the following statement must be displayed on the display surface of a child-resistant container that is an immediate container whose contents are to be used in their entirety immediately after the container is opened:

- “USE ENTIRE CONTENTS ON OPENING. THIS CONTAINER IS NOT CHILD-RESISTANT ONCE OPENED.”

- “UTILISER LA TOTALITÉ DU CONTENU APRÈS OUVERTURE. UNE FOIS OUVERT, LE CONTENANT N’EST PLUS UN CONTENANT PROTÈGE-ENFANTS.”

Exterior package

(2) Subject to subsection (4), the statement must also be displayed on the display surface of the exterior package, if any.

Exception — immediate container

(3) If the main display panel of the immediate container has an area of less than 45 cm2, the statement need not be displayed on the display surface of the immediate container.

Exception — exterior package

(4) If the main display panel of the exterior package has an area of less than 45 cm2, the statement must be displayed on a tag attached to the immediate container.

Exception — immediate container that is not packaged

(5) If the main display panel of the immediate container has an area of less than 45 cm2 and the immediate container is not packaged, the statement must be displayed on a tag attached to the immediate container.

Toxicity information

57 (1) The following information must be displayed on the display surface of the immediate container of a vaping substance that contains nicotine in a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more:

- (a) an exact reproduction, except with respect to size, of the hazard symbol set out in Schedule 1; and

- (b) the following toxicity warning and first aid treatment statement:

- “POISON: if swallowed, call a Poison Control Centre or doctor immediately.”

- “POISON : en cas d’ingestion, appeler immédiatement un centre antipoison ou un médecin.”

Exception — vaping device and vaping part

(2) If the immediate container is a vaping device or vaping part and it is not packaged, the information must be displayed on a tag attached to the vaping device or vaping part, as the case may be.

Exterior package

(3) The information must also be displayed on the display surface of the exterior package, if any.

Exception — exposure to vaping substance

(4) However, the information is not required if exposure to a vaping substance that is in a form other than an aerosol is impossible during the reasonably foreseeable use of the container.

Vaping device and vaping part

58 Despite sections 56 and 57, the information required by those sections need not be displayed on the display surface of an immediate container that is a vaping device or vaping part.

Presentation of Information

Languages, legibility and durability

59 The information required under this Part must

- (a) be displayed in both official languages;

- (b) be clear and legible and remain so throughout the useful life of the vaping substance, or in the case of a refillable immediate container, throughout its useful life, under normal conditions of transportation, storage, sale and use; and

- (c) be displayed in black type on a white background.

Information in words — general rules

60 (1) If the required information is set out in words, the words must be displayed in a standard sans-serif type that

- (a) is not compressed, expanded or decorative;

- (b) as illustrated in Schedule 2, has a large x-height relative to the ascender or descender of the type;

- (c) in the case of an immediate container or exterior package whose main display panel has an area equal to or greater than 45 cm2, has a minimum height of 3 mm and a minimum body size of 8 points; and

- (d) in the case of an immediate container or exterior package whose main display panel has an area of less than 45 cm2, has a minimum height of 2 mm and a minimum body size of 6 points.

Measurement of height of type

(2) The height of the type must be determined in accordance with subsection 28(2).

Characters in text

(3) Each character in the text of the required information must have the same font and type size.

Order of presentation of ingredients

61 (1) The ingredients set out in the list of ingredients referred to in section 47 must,

- (a) in the case of ingredients that are present in the vaping substance in a concentration of 1% or more, be set out in descending order of their proportions; and

- (b) in the case of ingredients that are present in the vaping substance in a concentration of less than 1%, be set out in any order and immediately following the ingredients referred to in paragraph (a).

Concentration of ingredient

(2) In this section, when the concentration of an ingredient in a vaping substance is expressed as a percentage, the percentage represents the ratio of the weight of that ingredient to the volume of the vaping substance.

Concentration — combination of flavours

(3) In the case of ingredients that are added to a vaping substance solely to produce a combination of flavours, the proportion of the total concentration of those ingredients must be used to determine the order of setting out the indication “flavour” in the list of ingredients.

Directions to open and close

62 (1) The directions for opening and, if applicable, closing a child-resistant container that are referred to in section 55 must be set out using either or both

- (a) words;

- (b) a diagram or self-explanatory symbol.

Official languages

(2) If the directions are set out in words, they may be displayed in one official language on the closure system of the child-resistant container and repeated elsewhere on the display surface of the container in the other official language.

Diagram or symbol — colour contrast

(3) If the directions are set out in a diagram or symbol, the contrast between the colour used for the information and that used for the background must be equivalent to at least a 70% screen of black on white.

Hazard symbol — minimum diameter

63 The hazard symbol referred to in paragraph 57(1)(a) must,

- (a) in the case of an immediate container or exterior package whose main display panel has an area equal to or greater than 45 cm2, have a diameter at least as large as the diameter of an imaginary circle that has an area equal to 3% of the main display panel; and

- (b) in the case of an immediate container or exterior package whose main display panel has an area of less than 45 cm2, have a diameter of at least 6 mm.

Toxicity warning and first aid treatment statement

64 The toxicity warning and first aid treatment statement referred to in paragraph 57(1)(b) must be displayed in such a manner that

- (a) the word “POISON” is in bold-faced, upper case letters; and

- (b) the statement is located immediately beside or below the hazard symbol referred to in paragraph 57(1)(a).

PART 3

Transitional Provision, Related Amendment and Coming into Force

Transitional Provision

Toxicity information

65 (1) The information on the toxicity of a vaping substance referred to in section 57 may, despite subsection 39(1) of the Consumer Chemicals and Containers Regulations, 2001, be displayed in accordance with these Regulations on a container that is an immediate container, other than a vaping device or vaping part, during the period beginning on the day on which these Regulations are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, and ending on June 30, 2020.

Definition

(2) In this section, container has the same meaning as in subsection 1(1) of the Consumer Chemicals and Containers Regulations, 2001.

Related Amendment

Canada Consumer Product Safety Act

Consumer Chemicals and Containers Regulations, 2001

66 The Consumer Chemicals and Containers Regulations, 2001 footnote 1 are amended by adding the following after section 1:

Non-application

Vaping products

2 These Regulations do not apply to vaping products as defined in section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act.

Coming into Force

July 1, 2020

67 (1) Subject to subsections (2) and (3), these Regulations come into force on July 1, 2020.

January 1, 2021

(2) Section 50 comes into force, in respect of an immediate container that is a vaping device or vaping part, on January 1, 2021.

Publication

(3) Section 65 comes into force on the day on which these Regulations are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

SCHEDULE 1

(Subsection 43(1) and paragraph 57(1)(a))

HAZARD SYMBOL

SCHEDULE 2

(Subparagraph 28(1)(a)(iii) and paragraph 60(1)(b))

ILLUSTRATION — STANDARD SANS-SERIF TYPE

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: Nicotine is the substance in tobacco products that causes dependence and drives the long-term use of these harmful products. There are concerns that the use of vaping products with nicotine by youth and non-users of tobacco products could lead to the use of tobacco products. Currently, there are no regulations that require the display of a warning about the addictiveness of nicotine or set out where and how information about the nicotine content of a vaping product be displayed on the product or its packaging.

Nicotine is highly toxic when ingested. Health Canada is aware of four fatalities of young children outside Canada and several non-fatal poisoning incidents in Canada related to the ingestion of vaping substances containing nicotine. Some requirements to help protect against vaping substance ingestion are already in place under the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), but there are gaps in protection, particularly regarding refillable vaping devices and their parts.

Description: Health Canada is publishing a single set of regulations under the authorities of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA) and the CCPSA. The Regulations set out the requirements in two parts: labelling requirements pursuant to the TVPA, and labelling and child-resistant container requirements pursuant to the CCPSA. The labelling requirements include a list of ingredients and, for products containing nicotine, a health warning that nicotine is highly addictive, the concentration of nicotine, and warnings regarding the toxicity of nicotine when ingested. In addition, the Regulations set out expressions that may be used on the product or package to indicate when a vaping product is without nicotine. The Regulations also require refillable vaping products, including devices and their parts, to be child-resistant.

Cost-benefit statement: The Regulations impose costs on the vaping industry and the Government of Canada. A cost-benefit analysis estimated that the present value costs for industry related to the labelling provisions would be $3,234,500 (or an annualized average of $260,500), and those for the child-resistant container provisions would be $9,346,000 (or an annualized average of $753,000), which amount to a total of $12,580,500 (or an annualized average of $1,013,500). The government costs are estimated to be about $3,000,000 in present value (or an annualized average of $223,000) for compliance promotion, monitoring, and enforcement. The labelling requirements will result in benefits by increasing awareness of the health hazards of vaping products and will enable the people of Canada to make informed choices regarding their use, including avoiding exposure to nicotine. The combination of mandating toxicity warnings and child-resistant container requirements will also provide benefits by helping to protect against poisoning incidents and fatalities. The analysis suggested that the benefits of the child-resistant container provisions would exceed their costs if one emergency room visit was avoided every 7 to 29 days or one death was avoided every 24 to 92 years.

One-for-one rule and small business lens: The small business lens applies. The one-for-one rule also applies, as manufacturers and importers will have to obtain and maintain records with respect to the child-resistant container requirements. Nonetheless, having a single, product-specific regulation that sets out labelling requirements using authorities under the CCPSA and the TVPA will help to reduce the burden on small businesses.

Domestic and international coordination and cooperation: The Regulations will implement measures that are similar to those taken in the European Union for vaping products containing nicotine, which are required to display, among other things, a health warning regarding the addictiveness of nicotine and to provide information on the toxicity of nicotine. The child-resistant container requirements for refillable devices, and for stand-alone containers of vaping substances containing nicotine, are similar to the controls currently in place in the European Union. In the United States, a health warning regarding the addictiveness of nicotine is required for vaping products containing nicotine, and stand-alone containers of vaping substances containing nicotine must be child-resistant.

Issues

An Act to amend the Tobacco Act and the Non-smokers’ Health Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts (referred to hereafter as “the Act”) received royal assent on May 23, 2018. The Act established a new legislative framework in Canada to govern vaping products, which consist of vaping substances, vaping devices and their parts. Vaping products are subject to the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA) and either the Food and Drugs Act (FDA) or the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), depending on whether or not the product is marketed for a therapeutic use. The Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations (hereafter “the Regulations”) are the first set of regulations under the Act to address the issues discussed below.

Nicotine toxicity

Nicotine is a highly toxic substance when ingested. A 2016 market study by Health Canada indicated that 86% of vaping substances marketed in Canada contain nicotine. Young children are curious by nature and explore their world with all their senses, including taste. footnote 2 To the knowledge of Health Canada, ingestion of vaping substances containing nicotine has resulted in four reported fatalities in young children. These incidents occurred in Israel in 2013, the United States in 2015, South Korea in 2016 and Australia in 2019. Additionally, Health Canada is aware of a number of non-fatal poisoning incidents, including some that occurred in Canada. The Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program data show that while there were no reports of injuries prior to 2013, there were 32 reported injuries related to vaping products between January 2013 and August 2018. footnote 3 Seventy-eight percent (78%) of the injuries reported were poisonings from ingesting a vaping substance, and 92% of those were among children aged four years or younger. Nearly two thirds (64%) of the vaping substances poisoning cases, among all age groups, specified that nicotine was involved. The rise in paediatric poisoning cases in Canada in recent years corresponds to a rise in sales of refillable vaping devices. footnote 4

Current requirements for vaping products under the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act

Upon royal assent of the Act, vaping products that contain nicotine and are not marketed for a therapeutic use were considered consumer products and subject to the CCPSA. These vaping products must comply with CCPSA provisions, which prohibit the manufacture, importation, advertisement or sale of consumer products that are a danger to human health or safety. Further, vaping substances containing nicotine at certain concentrations became subject to the Consumer Chemicals and Containers Regulations, 2001 (CCCR, 2001). These Regulations set out child-resistant container and toxicity warning requirements for stand-alone containers of vaping substances containing nicotine. The mandatory requirements imposed under the CCPSA and the CCCR, 2001 are intended to address risks posed by the acute toxicity of nicotine when ingested. Health Canada is currently enforcing these requirements. As described above, the existing requirements for vaping products regulated under the CCPSA allow Health Canada to address many of the risks posed by the acute toxicity of ingested nicotine.

However, there is one additional risk that was not addressed through the previous mandatory requirements. Vaping devices and their parts, including refillable tanks, did not need to meet the requirements from the CCCR, 2001 as a result of an exemption in the CCPSA that was put in place and came into force in May 2018. This exemption was put in place upon royal assent of the Act to allow industry time to source products that would meet the child-resistant container requirements.

Addictiveness of nicotine

Nicotine is a highly addictive substance. It is the substance in tobacco products that causes the addiction that drives long-term use and, as a result, repeated exposure to toxic chemicals in tobacco and its emissions. Vaping products deliver nicotine via inhalation of an aerosol formed when a nicotine-containing vaping substance is heated. In 2018, the United States National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine concluded that “there is substantial evidence that e-cigarette use results in symptoms of dependence on e-cigarettes.” footnote 5

Additional labelling concerns

A study conducted for Health Canada in 2017 showed diverse labelling practices among vaping product manufacturers. In particular, while the nicotine concentration did appear on most products, or their packaging, there was no consistency in how the information was presented. When present, there was also wide variation in the health warnings with few products indicating that nicotine is addictive. Given these additional findings and the concerns they raise, the powers of the TVPA are used to require that consumers be consistently informed about the presence of nicotine in a vaping product and about the addictiveness of nicotine. Also, specific expressions are prescribed in the Regulations to indicate that a vaping product is without nicotine.

Background

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of premature death and disease in Canada. Each year, approximately 45 000 people in Canada die from smoking-related diseases. Canada’s Tobacco Strategy aims to protect the health of the people of Canada, especially young people, from the dangers of tobacco use, including by helping the people of Canada quit smoking or reduce the harms of nicotine addiction.

While scientific knowledge is evolving, there is a consensus in the scientific community that for people who smoke, completely switching to vaping is less harmful than smoking conventional cigarettes. However, while vaping products may bring public health benefits if they reduce tobacco-related death and disease by helping adult tobacco users either quit or switch completely to a less harmful source of nicotine, these products are not harmless.

Most vaping products contain nicotine, which is highly addictive. Children and youth are especially susceptible to the risk of dependence.

Youth experimentation with and uptake of vaping could lead to tobacco use. Over a dozen studies show that among never-smoking youth, vaping significantly increases the risk of tobacco initiation.

Vaping products are also particularly harmful to youth and non-smokers because while they are less harmful than cigarettes, they emit chemicals during use that could negatively affect the health of youth and non-smokers. The potential short and long-term effects of vaping products remain unknown, and there is limited research on the effects of second-hand vapour.

Furthermore, nicotine is a highly toxic substance when ingested. Vaping products therefore pose health and safety risks, especially to young children who may gain access to the product and its contents in a household.

Vaping products were introduced commercially to the global marketplace in 2006. Over the past decade, Canada and the world have seen a rise in the popularity of vaping products. They are referred to by many different names, including e-cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems, vapes, vape pens, etc., and vary in design and appearance. For the purposes of the Regulations, vaping products consist of vaping substances, vaping devices and their parts. The vaping substance, which includes substances commonly called e-liquids, is contained in a reservoir or tank within the device, and is normally drawn into an atomizer that creates an aerosol that is inhaled by the user. Technology continues to evolve rapidly in this area and there are many types of vaping device designs, such as

- closed devices that are not refillable;

- open devices that are refillable;

- devices that use cartridges that are prefilled and disposable;

- devices that use cartridges that are refillable; and

- devices that are completely customizable.

Vaping substances are primarily composed of propylene glycol and/or glycerol (sometimes referred to as vegetable glycerine), flavouring ingredients and often nicotine. A large number of vaping substances are available in Canada, with new formulations continually being introduced. Vaping substances may be sold in a stand-alone container ready-mixed by the manufacturer or custom-mixed in vaping shops. Vaping substances are also available in prefilled cartridge formats that are not intended to be refilled. Vaping substances are a recurring purchase, since they are consumed during vaping and are essential to the practice.

Legislative background

In May 2018, the Act amended the Tobacco Act to extend its scope to the manufacture, sale, labelling, and promotion of vaping products and to change its title to the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA). Its purpose statement was also modified to include, among others, the goals of preventing the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products, and of enhancing public awareness of those hazards.

As defined in section 2 of the TVPA, vaping product means

- “(a) a device that produces emissions in the form of an aerosol and is intended to be brought to the mouth for inhalation of the aerosol;

- (b) a device that is designated to be a vaping product by the regulations;

- (c) a part that may be used with those devices; and

- (d) a substance or mixture of substances, whether or not it contains nicotine, that is intended for use with those devices to produce emissions.

- It does not include devices and substances or mixtures of substances that are excluded by the regulations, cannabis, as defined in subsection 2(1) of the Cannabis Act, cannabis accessories, as defined in that subsection, tobacco products or their accessories.”

Under the TVPA, the packaging, manufacture and sale of vaping products are prohibited unless the product and/or its package display, in the prescribed form and manner, the information required by regulations.

The Act also amended the CCPSA by replacing the previous wording of items 3 and 4 of Schedule 1 of that Act with the following:

- 3. Devices within the meaning of section 2 of the Food and Drugs Act, except a vaping product within the meaning of section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act that is not subject to the Food and Drugs Act.

- 4. Drugs within the meaning of section 2 of the Food and Drugs Act, except a vaping product within the meaning of section 2 of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act that is not subject to the Food and Drugs Act.

Pursuant to these amendments, Health Canada is authorized to administer the CCPSA for the purposes of addressing health or safety issues relating to vaping products including those containing nicotine, but not vaping products within the meaning of section 2 of the TVPA that are subject to the FDA.

Vaping products with or without nicotine that are marketed for a therapeutic use continue to be regulated under the FDA, while being regulated under the TVPA, except where expressly excluded by the Regulations Excluding Certain Vaping Products Regulated Under the Food and Drugs Act from the Application of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act.

Interim application of the CCCR, 2001 under the CCPSA

At this time, Health Canada has identified nicotine to be the only known ingredient of concern in vaping substances, related to toxicity by ingestion. Health Canada has assessed the toxicity of nicotine when ingested and, on the basis of that assessment, has determined the following:

- 1. Vaping substances, which are to be sold as consumer products, containing equal to or more than 66 mg/mL nicotine footnote 6 meet the classification of “very toxic” under the CCCR, 2001 and are prohibited from manufacture, import, advertising or sale under section 38 of the CCCR, 2001.

- 2. Vaping substances, which are to be sold as consumer products, containing between 10 mg/mL and less than 66 mg/mL nicotine meet the classification of “toxic” and are subject to all applicable requirements under the CCCR, 2001 for toxic chemicals. Stand-alone containers of vaping substances intended for sale at retail are required to be sold in child-resistant containers, and to be labelled in accordance with the applicable CCCR, 2001 requirements, including a toxic hazard symbol on the container’s main display panel.

Applicability of sections 7 and 8 of the CCPSA

The CCCR, 2001 classification scheme for the determination of toxicity does not apply to ingredients present in concentrations of less than 1% (which in the Regulations is expressed as 10 mg/mL). Therefore, the CCCR, 2001 do not apply to vaping substances containing less than 10 mg/mL nicotine. However, a risk assessment conducted by Health Canada determined that nicotine at concentrations between 0.1 mg/mL and less than 10 mg/mL is potentially toxic when ingested and may contravene sections 7 and 8 of the CCPSA. As a consequence, in order to address this risk, Health Canada has communicated to industry that vaping substances within this range must adhere to all requirements of the CCCR, 2001 for “toxic” products, including the requirements for a child-resistant container.

The existing requirements and prohibitions will continue to apply to vaping substances that contain nicotine at concentrations of 0.1 mg/mL or more until the coming-into-force date of July 1, 2020. There are currently no child-resistant container requirements for refillable vaping devices or their parts and these specific provisions will come into force on January 1, 2021.

Recommendations regarding vaping products regulations

Canada is a Party to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Although vaping products are not captured in the scope of the FCTC, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a report in 2016 on vaping products in response to a request made by the Conference of the Parties to the FCTC. footnote 7 Among other things, the report recommends that Parties that have not banned the importation, sale, and distribution of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) / Electronic Non-Nicotine Delivery Systems consider the following options to minimize health risks to users and non-users:

- Regulate appropriate labelling of devices and vaping substances;

- Require health warnings about potential health risks deriving from their use. Health warnings may additionally inform the public about the addictive nature of nicotine in ENDS; and

- Reduce the risk of accidental acute nicotine intoxication by requiring tamper evident / child-resistant packaging for vaping substances and leak-proof containers for devices and vaping substances, and limiting the nicotine concentration and total nicotine amount in devices and vaping substances.

Countries have adopted various regulatory strategies with respect to vaping products. According to a policy scan prepared by the Institute for Global Tobacco Control, there are 98 countries that have national/federal laws regulating vaping products, including laws related to the sale (including minimum age), advertising, promotion, sponsorship, packaging (child-resistant packaging, health warning labelling, and trademark), product regulation (nicotine volume/concentration, safety/hygiene, ingredients/flavours), reporting/notification, taxation, use (vape-free) and classification of vaping products. footnote 8 Of these countries, 28 have banned the sale of all types of vaping products and an additional 7 countries prohibit the sale of vaping products containing nicotine. footnote 9 In the countries that permit vaping products, 38 mandate the placement of health warnings on packaging and 31 have regulations on child-resistant packaging. footnote 10

In March 2015, Canada’s House of Commons Standing Committee on Health issued its report titled “Vaping: Towards a regulatory framework for e-cigarettes.” footnote 11 The Committee put forth 14 recommendations, one of which invited the Government of Canada to “… require that electronic cigarette components be sold in child-resistant packaging, and that all packaging clearly and accurately indicate the concentration of nicotine and contain appropriate safety warnings about the product.”

Objectives

The objectives of the Regulations are twofold, drawing from the authorities of the TVPA and the CCPSA.

The first objective of the Regulations is to use the authorities set out in the TVPA to help protect young persons and non-users of tobacco from exposure to, and dependence on, nicotine and to help prevent vaping product use leading to the use of tobacco products. More specifically, the Regulations aim to enhance awareness of the health hazards of using vaping products and prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards posed by their use.

The second objective of the Regulations is to use the authorities set out in the CCPSA to help protect the health and safety of young children by reducing the risk that they ingest vaping substances containing toxic concentrations of nicotine. More specifically, the Regulations

- prohibit vaping products with nicotine concentrations of 66 mg/mL or more;

- require stand-alone containers of vaping substances containing nicotine in a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more to be child-resistant and display toxicity warnings on product labels;

- require refillable vaping devices and their parts to be child-resistant; and

- require all vaping substances to display an ingredient list on product labels.

Description

The Regulations set out requirements under the authority of the TVPA and the CCPSA. The provisions under the TVPA apply to vaping products and their packaging that are intended for retail sale or to be furnished footnote 12 by any means other than retail sale to a consumer in Canada. As mentioned in the “Legislative background” section, the TVPA applies to all vaping products, including those subject to the FDA, unless expressly excluded. The labelling requirements set out in Part 1 of the Regulations, which are under the authority of the TVPA, do not apply to those vaping products subject to the FDA. The requirements in Part 2 of the Regulations, which are under the authority of the CCPSA, apply only to vaping products that are consumer products, that is, those not subject to the FDA.

PART 1: Requirements under the authority of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act

1. Vaping products containing nicotine

There are two labelling elements required for vaping products that contain nicotine: a nicotine concentration statement and a health warning about the addictiveness of nicotine. These labelling elements must be displayed on vaping products and/or their packaging, as the case may be, when the vaping product contains nicotine. In certain cases, the use of tags or leaflets is permitted. The information must respect the legibility and visibility requirements set out in the Regulations. The health warning must be displayed in both official languages.

For vaping substances in liquid form, Health Canada has developed a method, namely, Method C57.1: Determination of Nicotine at Low Concentration in Liquids used in Electronic Nicotine Devices by GC-MSD/FID, to assist regulated parties in determining if the substance contains nicotine. The title of this method is published on the Government of Canada website and the method is available upon request from the Government of Canada. footnote 13 For compliance and enforcement purposes, Health Canada may use the latest version of this method to determine when a vaping product is required to display the above noted labelling elements.

a) Nicotine concentration statement

For vaping products that contain nicotine, a statement of the nicotine concentration is required on the main display panel of the product or package. In certain cases, such as vaping devices and their parts that contain vaping substances with nicotine, this information may be displayed on a tag attached to the product. For the nicotine concentration statement, the word “Nicotine” is required and the concentration must be expressed in mg/mL for all forms of vaping substances.

b) Health warning

The nicotine addictiveness warning is “WARNING: Nicotine is highly addictive.” (“AVERTISSEMENT : La nicotine crée une forte dépendance.” in French). This health warning is required to appear on the main display panel of the product or package in both official languages. When a vaping product is sold without packaging or if the packaging or product is very small, this information may be displayed on a tag or in a leaflet, as the case may be.

The health warning is provided in a separate document entitled “List of Health Warnings for Vaping Products” and is available on the Government of Canada website. This document is incorporated by reference in the Regulations in a version that can be amended from time to time. This gives Health Canada flexibility to amend the health warning as new scientific evidence emerges on vaping products. Stakeholders will be notified of any proposed change to the list of health warnings. The Regulations allow for a 180-day transitional period after any change to the list to allow time to modify the health warnings that are used on the product and its packaging.

2. Vaping products that do not contain nicotine

The Regulations set out three permitted expressions that may be used when a vaping substance does not contain nicotine and, in the case of any other vaping product that contains a vaping substance, the product is without nicotine. These expressions are:

- Nicotine-free / Sans nicotine

- No nicotine / Aucune nicotine

- Does not contain nicotine / Ne contient pas de nicotine

The use of one of these expressions on the product or package is voluntary. It is the manufacturer’s responsibility to ensure that the permitted expression is used only on a product that does not contain any nicotine.

The purpose of these standardized expressions is to prevent the consumer from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards or effects of the product. The intent is to prescribe consistent language about the absence of nicotine, on the product or package, to allow the consumer to make an informed choice about their use of vaping products.

PART 2: Requirements under the authority of the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act

The Regulations maintain and extend the prohibition on the manufacture, importation, advertisement or sale of vaping products containing 66 mg/mL or more of nicotine, which was already in force under the CCCR, 2001. Since nicotine is the only ingredient that is acutely toxic by ingestion known to be present in vaping substances, the Regulations provide an opportunity to avoid using general toxicity classification criteria and instead set out the appropriate nicotine concentration considered to be very toxic.

The Regulations set out requirements for vaping substances containing nicotine in a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more to be packaged in a child-resistant container. Such containers are required to display a toxicity warning including the toxic hazard symbol. These requirements do not apply if the container does not permit exposure to the non-aerosolized form of nicotine under reasonably foreseeable use. The Regulations also set out requirements for refillable vaping devices and their parts to be child-resistant.

Each of the elements above is discussed specifically in the following sections.

Prohibitions

Health Canada used the literature value of 3.3 mg/kg for the LD50 of pure nicotine. The CCCR, 2001 has a prohibition on very toxic consumer chemical products, which are defined as having an LD50 of 50 mg/kg or less. Modelled on this CCCR, 2001 prohibition, the Regulations prohibit any vaping product containing nicotine at concentrations of 66 mg/mL or more from being manufactured, imported, advertised or sold.

Requirements

The Regulations set out a child-resistant container requirement for any vaping product that may hold a vaping substance containing nicotine in a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more. The child-resistant container requirements are modelled on those found in the CCCR, 2001. The child-resistant container requirement applies to refillable vaping devices and their parts, including component tanks or reservoirs that may hold vaping substances, and to stand-alone containers of vaping substances containing nicotine in a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more. The Regulations include a requirement for importers and manufacturers to obtain and maintain records to demonstrate that the container meets the child test protocol requirements in one of the prescribed acceptable standards. The person responsible for the vaping product is required to maintain documentation to demonstrate that the closure on the container maintains its function for the lifetime of expected use. This person is also required to include labelling, on the closure or display surface of the container, that instructs proper operation of the closure by the user. Finally, any documentation must be kept for a period of at least three years.

Any container of a vaping substance containing nicotine in a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more is required to have the toxic hazard symbol appear on the container and outer package, as applicable. A cautionary statement next to it is required to state, in both official languages: “POISON: if swallowed, call a Poison Control Centre or doctor immediately.” (“POISON : en cas d’ingestion, appeler immédiatement un centre antipoison ou un médecin,” in French). The hazard symbol and statement is designed to draw a person’s attention to the fact that nicotine is acutely poisonous if ingested, and to provide emergency instruction should poisoning occur.

All vaping substances, whether or not they contain nicotine, are required to display a list of ingredients to allow consumers to make informed choices regarding the products they choose to use.

Exceptions

The Regulations establish various exceptions to the requirements laid out above. The child-resistant container requirements and toxicity warning labelling are not required when exposure to the vaping substance is not reasonably foreseeable, such as when the product is not refillable. In addition, refillable vaping devices and their parts are not subject to labelling requirements for toxicity warning, unless they are sold prefilled with a vaping substance containing nicotine in a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or more. In such cases, the toxicity warning is still required on the outer package, and where there is no outer package, the information is required on a tag attached to the product.

The Regulations set out an exception that persons responsible for the importation of a vaping product that does not comply with a requirement of the Regulations may import the product for the purposes of bringing it into compliance. This exception is considered necessary in order not to impede industry business models such as bringing foreign products into compliance with Canadian requirements for sale in Canada or export to another country.

Application of the CCCR, 2001

In order to clearly and efficiently regulate vaping products subject to the CCPSA under a new, product-specific regulatory instrument, the CCCR, 2001 has been amended.

Exclusion of vaping products from the application of the CCCR, 2001

In order for the labelling and child-resistant container requirements for vaping products to appear in only one regulation authorized under the CCPSA, the Regulations amend the CCCR, 2001 to remove vaping products from the application of the CCCR, 2001. Even though these products are removed from the application of the CCCR, 2001, they continue to be subject to the CCPSA.

An order to fix the date for the repeal of subsection 4(4) of the CCPSA

An order to fix the date for the repeal of subsection 4(4) of the CCPSA (which excludes vaping devices and their parts from the application of the provisions of the CCCR, 2001) has been published at the same time as the Regulations. This subsection of the CCPSA was an interim measure intended to be in effect until product-specific regulations were published under the CCPSA. Since the Regulations remove the applicability of the CCCR, 2001 to vaping products, it is appropriate to repeal subsection 4(4) of the CCPSA at this time.

Coming into force