Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 158, Number 45: Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions Cap Regulations

November 9, 2024

Statutory authority

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Sponsoring departments

Department of the Environment

Department of Health

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: As part of its commitment under the Paris Agreement, the Government of Canada (the Government) published the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP), which emphasized the urgent need to address climate change while also identifying the opportunities associated with moving towards a low-carbon economy. The ERP puts Canada on a path to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050: it includes measures to achieve Canada’s climate goals and seize new economic opportunities across all sectors of the economy. GHGs are the major contributor to climate change. The oil and gas sector has long been the largest source of GHG emissions in Canada. The 2024 National Inventory Report (NIR) notes that in 2022, the oil and gas sector was responsible for 31% of Canada’s GHG emissions, accounting for 217 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). Despite steady reductions in emissions intensity, while most other industrial sectors are reducing emissions and growing production, oil and gas emissions remain consistently high as production and economic activity in the sector continue to grow.

Although global demand for oil and gas is expected to decline as the global economy switches to cleaner fuels to address the urgent issue of climate change, global demand for oil and gas will continue for the foreseeable future. In a low-carbon world, improvements in emissions intensity are likely to improve the sector’s competitiveness over time. Therefore, decreasing emissions from the oil and gas sector is necessary, both to reach the Government of Canada’s emission reduction targets of 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050, and to ensure that the sector remains competitive well into the future. To remain competitive in this global market, it is important that Canada’s oil and gas sector reduce its emissions from production by deploying clean technologies while also exploring opportunities to transition to producing non-emitting products and services such as hydrogen and petrochemicals.

Description: The proposed Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions Cap Regulations (the proposed Regulations) would cap emissions from certain activities in the oil and gas sector and would prohibit operators from emitting GHGs from specified activities in the sector, unless the operator registers by submitting the required information to the Minister of the Environment (the Minister). Emissions allowances would be distributed to operators that are covered by the remittance obligations in the proposed Regulations, with the total number of allowances equal to the emissions cap. In addition to emissions allowances, operators with remittance obligations would be able to use a limited quantity of compliance flexibility units (eligible offset credits and decarbonization units). The emissions cap combined with the limited access to compliance flexibility would ensure GHG emissions do not exceed a legal upper bound.

The proposed Regulations would also make consequential amendments to the Output-Based Pricing System Regulations (OBPS Regulations) and to the Regulations Designating Regulatory Provisions for Purposes of Enforcement (Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999) [the Designation Regulations].

Rationale: The proposed Regulations would ensure that emissions from the oil and gas sector are reduced and establish the framework needed to ensure emissions decline over time in a manner that is consistent with a path towards net-zero emissions by 2050. The proposed Regulations are expected to achieve GHG reductions while enabling the sector to increase production from historic levels in response to global demand. This would address the Government’s objectives for the oil and gas emissions cap-and-trade system to establish a mechanism to ensure the sector reduces GHG emissions and is on a path to net-zero emissions in a way that allows the sector to compete in the emerging net-zero global economy.

Forecasts of global oil and gas demand are uncertain. The proposed Regulations are designed to account for changes in production and emissions in the near future by setting the emissions cap based on 2026 reported data, rather than relying on historic data and projections. This would provide sufficient time to set the actual emissions cap level and distribute allowances before the first compliance period begins in 2030.

A review of the proposed Regulations would conclude within five years after they come into force. This would include a review of global market dynamics, decarbonization technologies, technically achievable reductions and the access the sector has to compliance flexibilities. This information would be used to set the emissions cap for the post-2032 period.

In addition, the Government will monitor developments in the sector on an ongoing basis, and will take action as appropriate to ensure the full suite of policies and measures supporting decarbonization efforts reflect up-to-date information.

Cost-benefit statement: The costs and benefits of the proposed Regulations have been evaluated relative to a baseline that assumes production in the oil and gas sector grows, existing GHG policies and measures are in place, and the sector achieves a 75% reduction in methane emissions relative to 2012 levels consistent with the proposed Regulations Amending the Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector).

Over the time frame of this analysis (2025 to 2032), the proposed Regulations are estimated to result in net cumulative GHG emissions reductions of 13.4 Mt incremental to the policies and measures that are included in the baseline. These incremental reductions are valued at almost $4.0 billion in avoided climate change damages. The proposed Regulations are also estimated to have some incremental impacts on the economy, valued at $3.3 billion, and some administrative costs to industry and government estimated to be $219 million. The costs to the economy arise primarily from the costs to the sector to reduce emissions in response to the emissions cap. Thus, even without various benefits that are not considered, the proposed Regulations are estimated to have net benefits of $428 million. The impacts accounted for in this analysis do not include a comprehensive inventory of all the impacts of the proposed Regulations. They do not account for the benefits from reduced air pollution. They do not account for impacts on the jobs and associated economic activity from post-2032 investments in carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) and other major decarbonization activities to reduce emissions from the sector. Nor do the estimates fully consider the stimulation of new low-carbon industries, such as CCUS and clean hydrogen, or for the longer-term competitiveness benefits of a decarbonized Canadian oil and gas sector in a world that complies with existing commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Issues

There is an urgent need to address climate change and move towards a low-carbon economy. Canada is committed to doing its part to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs), the major contributor to climate change. Signatories to the Paris Agreement, including Canada, have collectively pledged to reduce GHG emissions to limit the global average temperature increase to below 2 °C, and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C to reduce the severity of climate impacts. Under the Paris Agreement, Canada committed to reduce GHG emissions by 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and has since committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 under the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act. To deliver on these climate objectives, the Government of Canada published the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP). This plan lays out the steps the Government of Canada has taken and intends to take to reduce GHG emissions across all sectors of the economy. These include capping GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector. According to the 2024 National Inventory Report (NIR), the oil and gas sector was responsible for 31% of Canada’s GHG emissions in 2022, accounting for 217 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). This makes the sector the largest GHG emitter in Canada. Therefore, decreasing emissions in the oil and gas sector by introducing a regulatory emissions cap is necessary for the sector to do its share to tackle climate change and reach the Government of Canada’s GHG emissions reduction targets.

Background

Oil and gas sector

The oil and gas sector can be grouped into three segments: upstream (including conventional onshore and offshore oil production, oil sands production, upgrading, and natural gas production and processing); midstream (oil, natural gas and carbon dioxide [CO2] transmission pipelines); and downstream (petroleum refining and natural gas distribution). Upstream oil and gas production is concentrated in Alberta (AB), Saskatchewan (SK), British Columbia (BC), and Newfoundland and Labrador (NL). There are also oil and gas wells in Ontario (ON), Manitoba (MB), the Northwest Territories (NWT), and New Brunswick (NB). Midstream infrastructure and downstream petroleum refineries, distribution terminals or bulk storage facilities are in every province and territory. Within the upstream, midstream, and downstream segments, there is a myriad of operators, ranging from small exploration and production firms to large integrated oil and gas companies.

The oil and gas sector is a major contributor to Canada’s economy. In 2022, it generated $187B in gross domestic product (GDP) and accounted for 30% of Canada’s exports (valued at $217B).footnote 1 The sector is also a major employer across the country, directly employing 171 800 people in 2022.footnote 1

GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector

The oil and gas sector accounts for a significant portion of Canada’s GHG emissions. The upstream sector accounts for about 26% of Canada’s emissions and about 85% of the entire oil and gas sector’s total emissions. GHGs are emitted from a number of sources at upstream oil and gas facilities, including stationary fuel combustion, venting, flaring, leakage, on-site transportation, industrial processes, industrial product use, waste and wastewater.

The GHGs emitted from Canada’s oil and gas sector include carbon dioxide, methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). Carbon dioxide accounts for the majority of GHG emissions from the sector, while methane accounts for the majority of the remaining GHG emissions from the sector. The oil and gas sector is the largest source of methane emissions in Canada. Methane is a potent GHG and also a smog precursor. The bulk of methane emissions from Canada’s oil and gas sector are from conventional oil production and natural gas production and processing.

Key decarbonization options for the oil and gas sector include electrification to reduce GHG emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels throughout the oil and gas sector; the use of solvents to dilute bitumen and reduce the need to produce and use steam for in situ oil sands production; fuel switching to low-carbon or renewable fuels such as hydrogen; energy efficiency measures and other process improvements; methane abatement; and CCUS.

Section 93 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) provides the authority to make regulations with respect to substances that are specified on the list of toxic substances in Schedule 1. The GHGs covered by the proposed Regulations are those listed in items 65 to 70 of Part 2 of Schedule 1 of CEPA.

Measures to reduce emissions from the oil and gas sector

A number of federal and provincial regulatory and supporting measures to reduce oil and gas sector emissions are in place or under development. These include multiple programs to support investments in decarbonization activities and technologies, the proposed Regulations Amending the Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) [the proposed Methane Regulations], federal and provincial carbon pricing systems, the Clean Fuel Regulations, as well as the proposed Clean Electricity Regulations.

These measures are expected to help reduce the oil and gas sector’s GHG emissions; however, they do not guarantee an emissions level across the entire oil and gas sector. The proposed Regulations would ensure the oil and gas sector lowers absolute emissions at a pace and scale necessary to ensure that the oil and gas sector plays a role in achieving Canada’s economy-wide climate commitments and support the transition to net-zero.

Commitment to cap emissions from the oil and gas sector

At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), the Prime Minister committed to cap and cut GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector at a pace and scale necessary to ensure the sector makes a meaningful contribution to Canada’s 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution of 40–45% below 2005 emissions levels by 2030 and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The commitment to cap emissions from the oil and gas sector was included in the ERP published in March 2022. In July 2022, the Government published a discussion document titled Options to Cap and Cut Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions to Achieve 2030 Goals and Net-Zero by 2050, which sought input on two options to cap GHG emissions from the sector: the development of a new cap-and-trade system under CEPA; or the modification of existing carbon pollution pricing. This document proposed that the emissions cap cover the upstream oil and gas sector and sought feedback on whether to also cover natural gas transmission pipelines and petroleum refineries.

Building on the feedback on the discussion document, the Government published the Regulatory Framework to Cap Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions (the Regulatory Framework) in December 2023. This confirmed cap-and-trade as the instrument through which the emissions cap would be implemented, and proposed a number of design features, notably scope of application (upstream oil and gas and liquified natural gas [LNG]), the approach to determining the emissions cap levels, and the compliance flexibility options that would be made available. Interested parties were invited to submit formal comments on the Regulatory Framework. The Regulatory Framework indicated that the proposed Regulations would be published in 2024 and final regulations would target 2025, with the first reporting obligations starting as early as 2026 and full system requirements phased in between 2026 and 2030.

Objective

The objective of the proposed Regulations is to reduce GHG emissions from certain activities carried out in the oil and gas sector. As proposed in the Regulatory Framework, the oil and gas emissions cap-and-trade system is designed to ensure that the sector reduces GHG emissions and is on a path to net-zero, thereby helping Canada to achieve its economy-wide GHG emissions reduction targets. It would also provide some flexibility to enable the sector to respond to changes in global demand and in a manner that will enhance the competitiveness of the sector moving forward in a world that complies with existing commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Description

The proposed Regulations would cap emissions from certain activities carried out in the oil and gas sector and would also prohibit GHG emissions (i.e. any substance referred to in any of items 65 to 70 in Part 2 of Schedule 1 to CEPA) from specified industrial activities in the sector unless the operator registers by submitting the required information to the Minister of the Environment (the Minister). Starting in 2030, operators that meet the threshold set out in the proposed Regulations would be prohibited from emitting any GHG from an industrial activity unless they remit sufficient eligible compliance units to cover their GHG emissions. The proposed Regulations define who would have obligations and what those obligations would be, including registration, reporting, and remittance of compliance units, and set out the rules regarding eligible compliance units which include emissions allowances, decarbonization units and Canadian offset credits.

Beginning in 2029, emissions allowances (for 2030) would be distributed free of charge to operators that are covered by the remittance obligation, with the total number of allowances equal to the emissions cap. The distribution would occur annually and would be based on operators’ historical production and the distribution rate for the applicable industrial activity, pro-rated such that the emissions cap is fully distributed each year.

In addition to emissions allowances, operators with remittance obligations would be able to remit a limited quantity of compliance flexibility units (eligible offset credits and decarbonization units). Thirteen months after the end of each of the first and second years of each three-year compliance period, covered operators would have to remit an emissions allowance or other eligible compliance unit for each tonne of 30% of the GHGs they emitted during those years (expressed as tonnes of CO2e). Thirteen months after the end of the third year, they would have to remit an emissions allowance or other eligible compliance unit for each tonne of GHGs that they emitted during the full three-year compliance period, net of what was remitted for the first and second years.

In this document, operators that are subject to a remittance obligation are referred to as “covered operators.” An operator whose cumulative production in a calendar year is equal to or above the annual threshold of 365 000 barrels of oil equivalent would become a covered operator and would remain a covered operator until its total production was less than half the annual threshold for four consecutive years. The emissions cap, combined with the limited access to compliance flexibility, would ensure GHG emissions from covered operators do not exceed the legal upper bound.

Industrial activities

The proposed Regulations would apply to all operators of upstream oil and gas facilities and LNG facilities that carry out the following industrial activities:

- Bitumen and other crude oil production, other than bitumen extracted through thermal in situ recovery or from surface mining, including

- extraction, processing and production of light crude oil (having a density of less than 920 kg/m3 at 15 °C),

- extraction, processing and production of bitumen or other heavy crude oil (having a density greater than or equal to 920 kg/m3 at 15 °C);

- Thermal in situ recovery of bitumen from oil sand deposits;

- Surface mining of oil sands and extraction of bitumen;

- Upgrading of bitumen or heavy oil to produce synthetic crude oil;

- Extraction of natural gas and natural gas condensates;

- Compression of natural gas between production wells, natural gas processing facilities or re-injection sites;

- Processing of natural gas or natural gas condensates into marketable natural gas and natural gas liquids; and

- Production of LNG.

Registration

The obligations under the proposed Regulations would be at the operator level. Operators of all existing facilities would be required to register prior to January 1, 2026. From January 1, 2026, operators would be prohibited from emitting any GHGs from their industrial activities unless they have first registered in accordance with the proposed Regulations.

Other obligations

Operators would be required to provide information through annual reports and meet remittance obligations for their industrial activities if these obligations apply to them. Because the threshold to be covered is on an operator basis, any obligations that apply to an operator, such as reporting and remittance, would apply to all industrial activities in all facilities they operate, regardless of facility size. Under the proposed Regulations, however, multiple facilities would be deemed to be a single facility (deemed facility) for the purposes of reporting, remittance, and other regulatory obligations if they

- have the same operator or an operator in common;

- are in the same province or territory; and

- are not required to report under a notice published by the Minister pursuant to subsection 46(1) of CEPA.

Where a facility’s operator changes during a calendar year, both operators would be responsible for meeting the requirements of the proposed Regulations, including reporting on emissions and remitting compliance units, for the part of the year for which they were responsible for the facility.

Reporting

Operators would also be required to report prescribed information to the Minister regarding their GHG emissions. If their total monthly cumulative production during any of the months between January 1, 2024, and July 1, 2025, were equal to or above a threshold of 30 000 barrels of oil equivalent, or if any of their facilities were required to report their GHG emissions in 2024 under a notice published by the Minister pursuant to subsection 46(1) of CEPA, operators would be required to submit their first reports on emissions by June 1, 2027, for the calendar year 2026. Operators that do not meet either of these criteria would be required to submit their first reports as of June 1, 2029, for the calendar year 2028. After first reporting, all operators would be required to continue to report for each calendar year in which GHGs are emitted as a result of an industrial activity that is carried out at their facility.

The proposed Regulations would require operators to provide two types of reports in addition to the initial registration:

- Annual reports: one report for each facility, as defined in the proposed Regulations (i.e. one report for each deemed facility and one for each other facility).

- Report on cumulative production: one report that includes the operator’s cumulative production across all facilities and information on the facilities operated by the operator in the relevant calendar year.

Annual reports would include quantity of production by specified industrial activity and the quantity of GHGs attributed to the facility (“attributed GHGs”). Operators would be required to have their annual reports verified by an accredited third party and to keep records in Canada. Should any errors or omissions be identified in their annual reports within five years of submission, operators would also be responsible for correcting them.

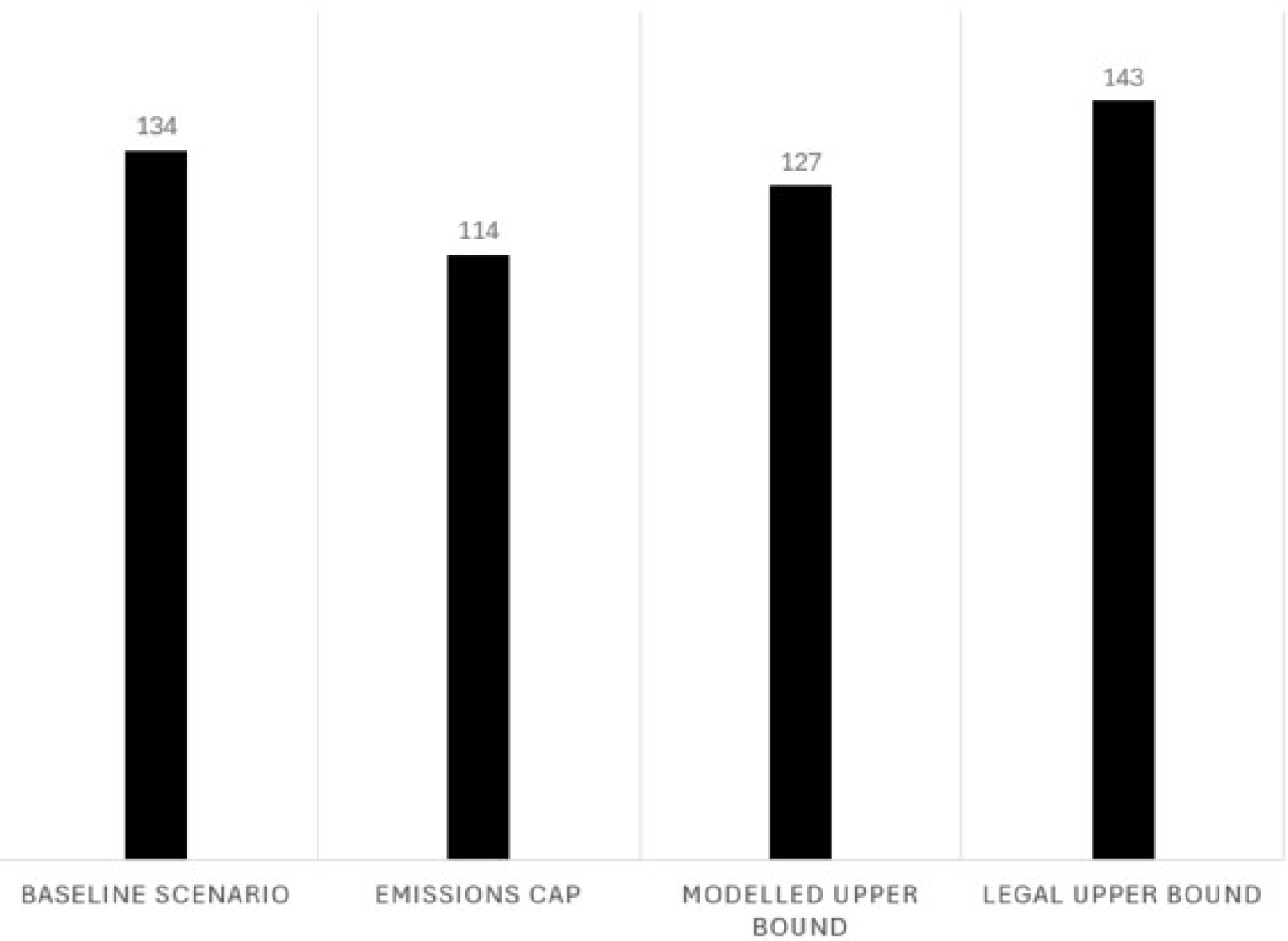

Emissions cap

The proposed Regulations would set the emissions cap for each year of the first compliance period at 27% below emissions levels reported for 2026 (i.e. only emissions from operators that are required to report in 2027 for 2026). That level is estimated to align with 35% below 2019 emissions levels, but would ensure that the actual cap reflects reported emissions and accounts for changes in production and emissions in the near future.

The sector would be permitted to emit above this level through the use of limited compliance flexibility mechanisms. If the use of compliance flexibilities were maximized, the sector could emit up to a legal upper bound estimated to be 19% below 2019 levels.

The emissions cap would remain at this level for subsequent compliance periods until regulatory amendments are made.

Attributed GHGs

Attributed GHGs are the amount of GHGs attributed to a facility that is reported in an annual report or, if applicable, that is reported in a corrected report or determined by the Minister. The calculation of attributed GHGs would need to be done in accordance with quantification methods set out in the document entitled Quantification Methods for the Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gases Emissions Cap Regulations. This calculation would take into consideration the emissions from all emissions sources at the facility, with the exception of electricity generation, carbon dioxide (CO2) that is permanently stored, and indirect emissions, meaning emissions attributed to thermal energy and hydrogen consumed (produced on-site or supplied to the facility). Operators would not be responsible for emissions attributed to the production of thermal energy and hydrogen that is transferred from the facility.

Compliance periods and remittance obligations

Compliance periods would cover three calendar years. The first compliance period would begin on January 1, 2030, and end on December 31, 2032. A covered operator would be subject to remittance obligations (i.e. would be required to remit one compliance unit for each CO2e tonne of their facility’s attributed GHGs during a compliance period) by the January 31 that is 13 months after the end of the compliance period. Covered operators would also be subject to an interim requirement to remit enough compliance units to cover at least 30% of their attributed GHGs during the first and second years of a compliance period no later than the January 31 that is 13 months after the end of the year of the attributed GHGs.

New facilities projected to emit 10 000 tonnes of CO2e or more in any of the facility’s first three years of operation would be subject to reporting requirements for the first four calendar years of their operation. The requirement to comply with remittance obligations would apply in the fifth calendar year that follows the year in which the operations start. For example, for a new facility that begins operating in 2029, the operator would submit reports annually for each calendar year starting with the 2029 calendar year. The first report would be due June 1 of 2030, for 2029. A report would then be submitted annually. In 2033, they would submit their annual report for the 2032 calendar year and receive emissions allowances for the 2034 calendar year. They would be required to meet the remittance obligation beginning January 1, 2034.

Emissions allowances

The Minister would distribute emissions allowances to covered operators on an annual basis up to the level of the emissions cap. Each emissions allowance would be distributed the year before the first calendar year in which they may be used to meet a remittance obligation (e.g. in 2029 for the 2030 calendar year). Allowances would be distributed to covered operators based on the distribution rate set out in the proposed Regulations for the applicable industrial activity (allowance per unit of production) and the three-year rolling average of historical production for each facility (e.g. 2026–2028 production levels would be used to allocate allowances in 2029 for the 2030 calendar year), taking into account the total allowances that can be distributed under the emissions cap. Allowances would be pro-rated across all operators in respect of a facility subject to remittance obligations to ensure that the total number of allowances distributed is equal to the emissions cap. Pro-rating would be based on the sum of the non–pro-rated number of allowances for all facilities divided by the emissions cap.

Compliance flexibility

In addition to emissions allowances, covered operators would have the option to remit eligible Canadian offset credits or decarbonization units (obtained by making contributions to a decarbonization program) to cover up to 20% of their remittance obligation. Covered operators would be able to remit any combination of Canadian offset credits or decarbonization units to meet their remittance obligation, up to specified limits. Up to 20% of a covered operator’s obligation within a compliance period could be satisfied with offset credits, and up to 10% of a covered operator’s obligation within a compliance period could be satisfied with decarbonization units obtained through contributions to a decarbonization program at $50/tonne of CO2e. Decarbonization units would not be tradable between operators or bankable to subsequent compliance periods. The proposed Regulations would require that contributions to the decarbonization program be used to fund projects that support the reduction of GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector.

The total offset credits and decarbonization units remitted for a facility cannot exceed 20% of its total obligation within a compliance period. For example, if 5% of a facility’s remittance obligation is met with decarbonization units, the covered operator would be limited to a maximum of 15% use of offset credits for that facility.

Only offset credits issued under the Canadian Greenhouse Gas Offset Credit System Regulations and provincial offset units or credits recognized for use under the federal OBPS Regulations associated with the reduction or removal of GHG emissions that occurred no more than five calendar years before the compliance period for which the credit is remitted would be considered eligible offset compliance units under the proposed Regulations.

Cross-recognition of Canadian offset credits

Covered operators would be permitted to use eligible offset credits to meet coinciding obligations under recognized carbon pricing systems and the proposed Regulations if the following conditions are met:

- The offset credits are used for compliance under the carbon pricing system for a year within the three-year compliance period for which they are remitted under the proposed Regulations;

- The offset credits are used under the carbon pricing system in relation to the emissions from an industrial activity carried out by the operator in the same province or territory as the operator’s facilities for which they are remitted under the proposed Regulations; and

- The offset credits are used to fulfill a requirement under the carbon pricing system other than for a requirement that relates to an extraordinary situation, such as to replace a cancelled credit, or as compensation for non-compliance with a requirement.

The Department of the Environment (the Department) would establish a list of carbon pricing systems where cross-recognition is authorized. Proposed amendments to the OBPS Regulations would operationalize this approach where the federal Output-Based Pricing System (OBPS) applies. Operationalization of cross-recognition in other provinces and territories would depend on them making any necessary adjustments to their carbon pricing systems and entering into a recognition agreement between the Minister and the province.

The proposed conditions for cross-recognition would prevent double claiming, which is a form of double counting where an offset credit is used by more than one party to meet multiple and different obligations. Double claiming would be prevented because only one operator could use an eligible offset credit to meet their obligations associated with the GHG emissions from undertaking a consistent set of activities under a carbon pricing system and the proposed Regulations. Offset credits represent actual reductions and removals of GHG emissions. Their cross-recognition under a carbon pricing system and the proposed Regulations would treat these out-of-sector emission reductions consistently with in-sector abatement, which may assist an operator in meeting their obligations under a carbon pricing system and the proposed Regulations.

Consequential amendments

Consequential amendments would be made to the Output-Based Pricing System Regulations (OBPS Regulations) to modify provisions related to the recognition of provincial offset credits and their use under the federal OBPS. This would enable the recognition for use of certain offset credits under both the proposed Regulations and the federal OBPS.

Consequential amendments to the Regulations Designating Regulatory Provisions for Purposes of Enforcement (Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999) [the Designation Regulations] would also be made to list certain provisions of the proposed Regulations in the schedule to the Designation Regulations. When designated provisions are contravened and upon conviction, the offender would be subject to minimum fines and higher maximum fines. Offences chosen for designation are those involving direct harm or risk of harm to the environment, or obstruction of authority.

Regulatory development

Consultation

The Government has consulted with provincial and territorial governments, Indigenous partners, representatives from industry and environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), academics and experts, other government departments, and the public through bilateral and multilateral meetings, information webinars, and the receipt of formal submissions. Since November 2021, the Department has received over 250 submissions from organizations in response to two publications, held over 114 meetings, and hosted seven public webinars.

Engagement with interested parties

On July 18, 2022, the Department published a discussion document (“Discussion Document”), titled Options to Cap and Cut Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions to Achieve 2030 Goals and Net-Zero by 2050, and launched a 90-day public comment period seeking formal input on guiding principles and two regulatory options to cap GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector: (1) a new national GHG emissions cap-and-trade system under CEPA; and (2) modifications to existing carbon pricing systems.

To support engagement and facilitate input, the Department and Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) held a series of information and technical webinars. On December 7, 2023, the Department published the Regulatory Framework to Cap Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions (the Regulatory Framework). The Regulatory Framework proposed key aspects of the Government’s approach to establishing an emissions cap. The Government sought substantive responses to the proposed policy details in the Regulatory Framework and received 107 formal responses.

In addition to technical webinars, the Department and NRCan officials organized targeted bilateral and multilateral meetings to engage interested parties on the oil and gas emissions cap.

Public email campaigns

In response to both the 2022 Discussion Document and the Regulatory Framework, the Government received over 60 000 emails as part of email campaigns from citizens providing non-technical input regarding the Government’s commitment to establish an emissions cap. Campaigns in support (approximately 40 000 emails) called for more rapid and stringent application. Campaigns that did not support (approximately 20 000 emails) did so primarily on the basis of concerns about economic impacts. The 429 public submissions compiled and sent by an ENGO in response to the Discussion Document were largely supportive of ambitious actions to reduce oil and gas sector emissions.

Interested parties’ response to the 2023 Regulatory Framework

Feedback on the Regulatory Framework came primarily from oil and gas companies, other industry stakeholders, and ENGOs and other non-governmental organizations. Three provinces and a territory (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador and the Northwest Territories) and four Indigenous groups also provided input. In their comments, oil and gas-producing provinces and industry raised questions about the authority and rationale for an emissions cap, and raised economic and energy security considerations, and concerns about the stringency of the measure rather than technical feedback to inform the development of key design features. ENGOs, while supportive of the concept of an emissions cap, expressed concerns about some proposed aspects of the potential design. Indigenous groups presented a range of views, with many seeking protections for Indigenous rights and meaningful engagement.

Overview of changes from approach outlined in the Regulatory Framework

The proposed Regulations include some changes from the approach proposed in the Regulatory Framework. These reflect a review of the feedback provided by governments, stakeholders, and rights holders, as well as an additional internal analysis.

Approach to operator and facility coverage

The Regulatory Framework proposed exploring methods for defining and regulating smaller emitting facilities under the emissions cap-and-trade regulations.

Most industry stakeholders advocated for the exclusion of small oil and gas facilities from the emissions cap, citing concerns about adverse impacts to competitiveness, an increased administrative burden, the ability to participate in an emissions trading system, and potential impacts on remote production. ENGOs warned against creating incentives to bundle or unbundle operations based on the chosen threshold.

Given the structure of the conventional oil and gas sector, in particular where operators may control anywhere from one to hundreds of very small facilities, the proposed Regulations would apply to operators rather than facilities. Operators would be responsible for complying with the proposed Regulations for all facilities under their control, and all operators, regardless of size, would be required to register and meet all reporting obligations, with smaller operators initially exempt from reporting until 2028 to provide them with additional time to understand the details of reporting obligations and prepare to collect the required information. Reported information is critical to the functioning of the proposed Regulations. It provides data needed to monitor the effectiveness of the proposed Regulations in reducing emissions. For covered operators, the information is the basis for determining allowance allocations and compliance obligations. For other operators, the information provides the basis for allowance allocation should an operator become a covered operator in the future.

To determine which operators would be covered under the emissions cap — i.e. subject to remittance obligations and eligible to receive allowances — the proposed Regulations would apply a threshold. The threshold would be based on an operator’s cumulative production across all covered industrial activities rather than setting facility-level thresholds. Operators track facility production as part of regular business practices but do not necessarily quantify emissions from smaller facilities. Setting the threshold in units of production at a level that is expected to generally result in emissions of about 10 kilotonnes (kt) of GHG emissions for light oil facilities would ensure high levels of coverage of sector emissions while minimizing the regulatory burden on smaller businesses.

To further address these issues, the proposed Regulations would deem multiple facilities to be a single facility for the purpose of compliance where each facility has the same operator, is in the same province, and for which a report to the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program is not required. Facilities for which a report to the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program is required (currently those with annual emissions exceeding 10 kt of CO2e) would be treated as individual facilities whose operators have separate obligations, while for deemed facilities, operators have combined obligations under the proposed Regulations. This approach is expected to reduce the administrative burden of the proposed Regulations.

Approach to setting the emissions cap and the legal upper bound

The Regulatory Framework proposed two key values: (1) the emissions cap level, which is equivalent to the total emission allowances issued by the Government for a given year; and (2) the legal upper bound, which is the maximum emissions the sector would be allowed to emit that year, composed of the total number of emission allowances issued plus the maximum allowable quantity of other eligible compliance units.

The Regulatory Framework proposed that the legal upper bound in 2030 be set at a level that assumes that covered sources achieve technically achievable emission reductions by 2030 for production levels aligned with the Canada Energy Regulator (CER) Canada Net-Zero (CNZ) scenario. It also proposed that the 2030 emissions cap be set at a level slightly below what emissions would be if covered sources achieved technically achievable emission reductions by 2030 and production was at 2019 levels.

Stakeholders supported a clear and transparent approach to setting and reviewing the post-2030 emissions cap trajectory. Producers highlighted the short timeline to achieve significant reductions by 2030 and stated that a clear and transparent trajectory is important for de-risking investment. A variety of academic and ENGO perspectives were shared on how the emissions cap should be determined post-2030, but in general, the expectation was that it should align with the 2050 Canada Net-Zero goals.

The proposed Regulations would establish the emissions cap at 27% below 2026 reported emissions from covered operators, which, when combined with access to compliance flexibility, creates a legal upper bound on emissions that is expected to allow for some production growth and assumes the sector deploys a range of technically achievable emissions reductions during the first compliance period. The emissions cap for the first compliance period would remain in place for subsequent compliance periods, until there are amendments to the proposed Regulations to reset the cap.

The Government will monitor developments in the oil and gas sector on an ongoing basis and will take action as appropriate to ensure the full suite of policies and measures supporting decarbonization efforts reflect up-to-date information.

The proposed Regulations are designed to account for changes in production and emissions in the near future by setting the emissions cap based on 2026 reported data, rather than relying on historic data and projections. This will provide sufficient time to set the actual emissions cap level and distribute allowances before the first compliance period begins in 2030.

A review of the proposed Regulations will conclude within five years after they come into force. It will include a review of global market dynamics, decarbonization technologies, technically achievable reductions and the access the sector has to compliance flexibilities. The review will be used to inform potential amendments to the emissions cap for the post-2032 period.

Approach to allocation of emission allowances

The Regulatory Framework proposed allocating allowances free of charge based on a baseline production level and a free allocation rate for a given product or activity, and that allowances would be pro-rated to ensure total allowances do not exceed the emissions cap.

Provinces, territories and oil and gas industry stakeholders advocated against broad sector-based standards, highlighting that diverse factors influence the emissions intensity of oil and gas production across the country. Stakeholders generally supported an approach that rewards better emissions intensity performance, while some raised concerns that regions with higher emissions intensity for reasons beyond operator control and fewer abatement opportunities may be disadvantaged. Non-oil and gas industry stakeholders and one Indigenous group favored an approach that recognizes early movers and rewards best performers, with a variety of suggested approaches, ranging from accounting for trade exposure to uniform distribution. The vast majority of ENGOs advocated for auctioning emissions allowances as opposed to free allocation. ENGOs recommended that, if free allocation is the chosen approach, it should recognize better emissions performance. Although not included in the proposed Regulations, auctioning of allowances, either in combination with free allocation or as a means to distribute all allowances, may be considered during the regulatory review, for introduction in later compliance periods.

The proposed Regulations would allocate allowances to covered operators using distribution rates specified in a schedule for each industrial activity. Distribution rates would be set on a per unit of production basis rather than based on absolute emissions in order to incentivize emissions intensity improvements and reward lower emissions intensity production for a given activity. Distribution rates would be set based on estimates of 2019 emissions intensities for each activity, with the same percentage reduction applied to all activities. Care was taken during the setting of the legal upper bound to ensure the overall level of reductions would be technically achievable assuming production grows consistent with the Canada Net-Zero forecast, with different levels of reductions coming from different sub-sectors.

By allocating allowances based on a uniform rate, rather than based on estimates of technically achievable reductions at the sub-sector and geographical level, the emissions cap design encourages sub-sectors to reduce emissions in the most economically efficient manner, while ensuring the overall reductions required to maintain the legal upper bound are technically achievable. The percentage reduction that would be applied is an estimate of the expected reductions needed by the sector to achieve the proposed emissions cap level, given assumptions around increases in production. The rates would be applied to a three-year rolling average of historical facility production. This approach would enhance transparency around expected allocation levels, prioritize certainty, and ensure that operators know their free allocations prior to each year, while providing a relative benefit to early movers. Free allocations would be pro-rated so that the number of allocated allowances equals the emissions cap.

Access to compliance flexibilities

The Regulatory Framework proposed that, in addition to emissions trading, multi-year compliance periods, and credit banking, covered operators would have the option to remit domestic offset credits or make contributions to a decarbonization funding program to cover a limited portion of their GHG emissions.

Provinces, territories, and oil and gas industry stakeholders broadly supported an approach that provides compliance flexibility mechanisms, requesting that access either be maintained or increased over time. Several submissions expressed skepticism that sufficient offset credits would be available by 2030, and some suggested the expansion of recognized offsets would be required to meet demand. One Indigenous group preferred in-sector reductions to maintain the co-benefit of reducing air pollution. ENGOs generally argued that compliance flexibilities should be removed or minimized and then phased out aggressively.

Compliance flexibility mechanisms can play an important role in cap-and-trade systems. Key decarbonization solutions for the sector, including CCUS, require significant time to deploy. Flexibility mechanisms give operators of facilities more time to optimize investments in GHG emissions reductions. They can also improve cost certainty, and the use of robust domestic offset credits can provide a means of meeting a more ambitious emissions cap by incentivizing out-of-sector emissions reductions that would not otherwise occur. The proposed Regulations would allow covered operators to use compliance flexibility mechanisms to account for up to an overall limit of 20% of the attributed GHGs of their facilities. Compliance flexibilities would include contributions to a decarbonization program to a maximum of 10% of their attributed GHGs and the use of offset credits up to the full 20%.

When an operator takes in-sector abatement actions at a facility that is covered both by the proposed Regulations and carbon pricing system, that reduction in emissions could contribute to reducing the operator’s obligation under both systems. To treat the use of offset credits similarly, the proposed Regulations would allow, where authorized by the relevant federal or provincial carbon pricing systems, eligible domestic offset credits used to meet a coinciding carbon pricing obligation to be recognized towards obligations under the proposed Regulations, provided that the credit compensates for emissions by the same operator, in the same jurisdiction, for a year included in the compliance period, and obligations cover the same activities.

Use of contributions to the decarbonization program

The Regulatory Framework proposed that proceeds from the decarbonization program be used to support oil and gas sector decarbonization and help facilities that receive support from the program to decrease their emissions.

Oil and gas industry stakeholders supported returning contributions to a decarbonization program to the sector. Indigenous organizations had varying views on how contributions to the decarbonization program should be used, including support for in-sector abatement, renewable energy, transition away from fossil fuels, and funding Indigenous organizations to undertake projects related to GHG reduction and removals. ENGO suggestions included uses from supporting the sector’s energy transition to mitigating climate impacts in communities.

The proposed Regulations specify that contributions to the decarbonization program would support the reduction of GHG emissions in the oil and gas sector in Canada.

In response to the Regulatory Framework, Indigenous groups suggested that contributions to the decarbonization program be used to support phasing out of fossil fuels or to support Indigenous groups that have innovative emissions reductions solutions. Industry comments generally supported returning contributions to the oil and gas sector to support decarbonization. Some industry members advocated for contributions to be returned directly to those that made them, with a requirement that they be used for decarbonization. ENGOs did not support inclusion of a decarbonization program, but, if implemented, they generally supported contributions being used to support energy transition and mitigating climate impacts in communities. Some ENGOs indicated that they did not support proceeds being used to support CCUS projects.

The Department considered other uses of the proceeds as suggested by stakeholders but determined that supporting decarbonization of the oil and gas sector aligns with the objectives of the policy.

The Government will continue to engage with stakeholders on the approach to administering the decarbonization program.

Use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement recognizes that countries may cooperate in implementing their climate targets, to enable higher ambition than they could otherwise achieve on their own. An internationally transferred mitigation outcome (ITMO) is an accounting entry that reflects a quantity of GHG mitigation (emissions reductions or removals) that occurs in one country and that is voluntarily authorized and transferred for use toward another country’s climate target or other international mitigation purpose. The Regulatory Framework indicated that the Department was considering allowing ITMOs, in the form of carbon offsets, to be used as a possible compliance option for some portion of emissions that could be covered by domestic offset credits.

Overall, industry was generally supportive of increased access to compliance flexibility. Submissions advocated for prioritizing domestic offsets over ITMOs, and expressed a general skepticism regarding the supply of ITMOs by 2030 given the status of the development of international rules and infrastructure to support this market developing and other potential sources of demand in the market. Indigenous organizations expressed limited support for the use of ITMOs while expressing an overall preference for domestic offset credit use that directly contributes to reducing air pollution in Canada.

The proposed Regulations would not allow for the use of ITMOs as a compliance option; however, the Department intends to continue consulting on the issue, and ITMOs could be included as a compliance option in the final Regulations. Issues to consider before the Regulations are finalized include access to and limitations on the use of ITMOs, eligibility criteria, and necessary policies and infrastructure.

Treatment of emissions from electricity generation

The Regulatory Framework proposed that facilities would be responsible for emissions resulting from the consumption of electricity, whether directly produced by the facility or transferred from a third party. Most provinces and oil and gas industry stakeholders did not support covering emissions from electricity generation, arguing that the emissions intensity of supplied electricity is beyond the control of producers, disadvantaging operators in fossil-fuel heavy jurisdictions, and that coverage under the emissions cap would be duplicative of existing or proposed instruments. Stakeholders also argued that coverage of emissions from electricity would discourage the electrification of operations and the deployment of carbon capture technology. ENGOs and other stakeholders advocated for harmonization across systems, but ENGOs almost unanimously supported coverage of emissions from electricity generation in the proposed Regulations.

The Department notes that several other existing or proposed federal measures already offer incentives or require emissions reductions from electricity generation, including carbon pricing, the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-fired Generation of Electricity Regulations, and the proposed Clean Electricity Regulations. Therefore, emissions from electricity that is produced, regardless of whether it is used on-site or transferred for use outside the facility, as well as emissions associated with electricity supplied to the facility, would be excluded from an operator’s attributed GHGs under the proposed Regulations.

Treatment of other indirect emissions

The Regulatory Framework proposed that facilities would be responsible for emissions resulting from the consumption of thermal energy, and hydrogen, whether directly produced by the facility or transferred from a third party.

Some industry stakeholders and ENGOs expressed support for coverage of other indirect emissions.

Under the proposed Regulations, covered operators would be responsible for emissions attributed to thermal energy and hydrogen consumed (produced on-site or supplied to the facility). Covered facilities would not be responsible for emissions attributed to the production of thermal energy and hydrogen that are transferred from the facility. This approach would limit the scope of the proposed Regulations to only emissions associated with the production of oil and gas, while also preventing the movement of those emissions outside the emissions cap.

New facilities

The Regulatory Framework proposed that all new facilities would have to register before emitting GHGs from a covered industrial activity. The Regulatory Framework also indicated that the Department was considering delaying the start of a new facility’s first compliance period until after it reaches a set proportion of its design capacity, or two years after first producing a product, whichever came first. Provinces, territories and industry stakeholders raised concerns that the emissions cap would create barriers for new entrants and were supportive of a delay on compliance obligations and a dedicated reserve of allowances for new entrants. ENGOs did not support a delay in compliance obligations for new facilities. One ENGO and one academic recommended a reserve apportioned from the existing proposed allowances.

The proposed Regulations are not intended to create a regulatory barrier to entry. Operators of new large facilities (projected to emit 10 kt of CO2e or more annually) would be required to report for the first four calendar years of their operation, but the requirement to remit compliance units equal to their emissions would not apply until the fifth calendar year that follows the year in which the operations start. Operators of new facilities that emit less than 10 kt of CO2e annually who already operate a deemed facility would include the new facility as part of the deemed facility for reporting and remittance obligations, in the case where the operator is a covered operator, immediately upon starting operation. This would simplify administration and reflect the more rapid compositional changes that can occur with conventional oil and gas extraction.

Modern treaty obligations and Indigenous engagement and consultation

As required by the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, an assessment of modern treaty implications was conducted for the proposed Regulations. The assessment examined the geographic scope and subject matter of the proposed Regulations in relation to modern treaties in effect. The assessment did not identify any modern treaty obligations.

There is a statutory obligation pursuant to section 5 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA) to take, in consultation and cooperation with Indigenous peoples, all measures necessary to ensure that existing and new federal laws (statutes and regulations) are consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Government of Canada has taken a distinctions-based engagement approach, including conducting outreach and facilitating bilateral and multilateral engagement with national Indigenous organizations, regional Indigenous organizations, and First Nation, Metis and Modern treaty rights holders or their representatives.

Indigenous parties’ perspectives and input on the oil and gas emissions cap have varied; however, throughout engagement there was a shared priority to take action to address the harmful impacts of climate change, while emphasizing the need to work in respectful partnership with Indigenous Peoples in achieving those objectives.

Through meetings and official submissions, the Department heard concerns about the impacts of the proposed Regulations on Indigenous communities, such as higher energy prices and reduced energy security; lower revenues and project royalties; negative impacts on jobs, businesses, and communities; greater uncertainty due to increased policy layering; and removing opportunities for Indigenous equity ownership in resource projects. The Department notes that the proposed Regulations would not prohibit the exploration or development of new oil and gas resources and include provisions to minimize barriers to new and/or small operators, including those that are operating primarily for own use in remote regions.

Indigenous parties expressed a desire to continue to be engaged while noting that engagement capacity remains a persistent issue. In 2022, NRCan received two requests for participant funding, which were approved. NRCan notified the groups in July 2022. Some Indigenous parties also expressed dissatisfaction with the extent of engagement, some arguing that it represents a violation of UNDA. The Department remains committed to ongoing engagement and will continue to reassess potential impacts on Indigenous communities in cooperation and consultation with interested Indigenous parties throughout the regulatory development process and encourages Indigenous parties to provide comments on these proposed Regulations, which will inform the final Regulations.

Instrument choice

A range of policy options were identified to reduce GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector. The process for evaluating the instrument choice focused on options that could effectively abate emissions from the oil and gas sector. Consideration was given to three options: maintaining the status quo, modifying of the current carbon pricing approach, and developing a regulated emissions cap-and-trade system.

Maintaining the status quo was not considered to be a viable option, as this would not ensure GHG emissions in the oil and gas sector are reduced at the pace and scale needed to achieve net-zero by 2050. Several federal and provincial regulatory and supporting measures to reduce oil and gas sector emissions are in place or under development. These include the proposed Methane Regulations, federal and provincial carbon pricing systems and the Clean Fuel Regulations. However, without an oil and gas sector emissions cap in place, these existing and proposed measures would not provide sufficient certainty that the oil and gas sector will do its share in ensuring Canada will meet its international commitments to reduce GHG emissions. For these reasons, maintaining the status quo was not considered.

As noted above, the Government of Canada published a discussion document in July 2022 outlining two regulatory options to implement the emissions cap: modifying the current carbon pricing approach or establishing a new emissions cap-and-trade system. Modifying the existing carbon pricing systems would build on the existing federal approach to carbon pricing by setting out the emissions cap trajectory in policy and modifying the federal carbon pollution pricing benchmark criteria to incentivize the oil and gas sector to further reduce emissions, aligned with the emissions cap trajectory. Under output-based pricing systems for industry that apply in all major oil and gas jurisdictions in Canada, facilities have unlimited ability to comply through payment for excess emissions. Although output-based pricing systems for industry provide an incentive to reduce emissions, relying on these systems alone would not provide certainty in reducing GHG emissions in the oil and gas sector.

A national emissions cap is proposed to be developed and implemented through the proposed Regulations under CEPA. Emission allowances would be issued for each tonne of emissions allowed under the emissions cap each year. It is expected that through future amendments, the emissions cap would decline over time to reach net-zero by 2050. In addition to being technology-neutral, it provides the most certainty that GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector would decline. In consideration of these factors, the emissions cap-and-trade approach was deemed to be the best policy option.

Regulatory analysis

Following the publication of the Regulatory Framework, the Department engaged in an analytical process to determine the emissions cap and allowable compliance flexibility for the proposed Regulations. It also undertook an economic analysis of the expected costs and benefits, as described below.

The key regulatory design elements

The estimated emissions cap (total quantity of allowances issued) plus maximum use of compliance flexibility (which together make up the legal upper bound) reflect a bottom-up analysis of the level of emissions that could be attained if technically achievable emissions reductions were deployed for a specific production forecast. Technically achievable emissions reductions were estimated based on an assessment of the abatement technologies that can feasibly be deployed within the upstream and LNG activities in the oil and gas sector (the sector) by 2030–2032, considering the status of available technologies, the availability of equipment and labour, as well as timelines for permitting and approvals. The risks that not all technically achievable reductions would be implemented in time for the first compliance period were also assessed. The estimates were informed by materials provided by industry and other interested parties. To construct the bottom-up estimates for the emissions cap and legal upper bound, a conservative 2030–2032 bottom-up baseline emissions level was estimated by assuming 2019 emissions intensities (data from the last pre-pandemic year available) remain constant for the given production level. The estimates of technically achievable emissions reductions were then deducted from the resulting GHG emissions level.

The legal upper bound

The legal upper bound is designed to align with Canada’s commitment to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The production forecast used to develop the 2030 to 2032 legal upper bound was grounded in the CER CNZ scenario from its Canada’s Energy Future 2023 report, which is based on a scenario where Canada and other parties to the Paris Agreement achieve their interim and net-zero emissions targets. This scenario assumes Canada’s oil and gas sector grows production out to 2030.

The legal upper bound was set at a level consistent with covered sources implementing technically achievable emissions reductions by 2030 to 2032 with an adjustment to take into account the risk that not all technically achievable reductions may be implemented by that time, and for production levels aligned with the CNZ scenario. This resulted in a legal upper bound of 19% below 2019 levels.

Emissions cap

The emissions cap holds the sector accountable for GHG emission increases beyond 2019 levels, the last pre-pandemic year before the Government of Canada’s commitment to cap and reduce GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector. It was set such that the sector would have the option to use compliance flexibility for up to 20% of its emissions, or equal to an emissions cap level of 35% below 2019 levels. This is consistent with an emissions cap that is at a level slightly below what emissions would be in a scenario where covered sources attained technically achievable emissions reductions and 2019 production levels are assumed to remain constant over the 2030 to 2032 period.

To establish the emissions cap level in the proposed Regulations, the equivalent reduction relative to 2026 was estimated. This approach ensures that the emissions cap and the distribution of allowances for the first compliance period of 2030 to 2032 would reflect updated production and emissions information and would be based on GHG emissions data that have been quantified using the methods required by the proposed Regulations. A 35% reduction in emissions below 2019 levels is estimated to be equivalent to a 27% reduction below 2026 levels based on a projection of 2026 emissions. The 2026 emissions value used in this calculation was the 2026 emissions value in Canada’s most recent emissions projections. The actual megatonne (Mt) level of the emissions cap would be announced in late 2027 after all of the 2026 emissions data has been received and analyzed.

The legal upper bound is not codified in the proposed Regulations. Rather, the combination of the emissions cap and 20% access to compliance flexibility together form an effective legal upper bound on emissions.

Distribution rates

The allocation of emissions allowances would be based on the distribution rates included in Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the proposed Regulations and reflect facility-specific analysis using 2019 data, the most recent and complete data set available. The data used to set distribution rates was drawn from facility-specific data including information reported to the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program and departmental analysis based on other publicly available information. The rates for all industrial activities are set at 45% below 2019 emissions intensities, which reflect an estimate of the level of allowances that would be allocated for each year in the first compliance period, taking into account the emissions cap level and growth in production from 2019 levels based on the CNZ forecast. If emissions intensities or production levels are higher or lower than expected, allowance allocations would be pro-rated up or down to ensure the number of allowances is equal to the emissions cap in each year.

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) summary

The Department employed a bottom-up approach to set the emissions cap and legal upper bound as described above. This bottom-up approach provides a high degree of confidence that the emissions reductions required from the sector will be technically achievable, assuming production grows in line with the CNZ forecast and compliance flexibility mechanisms are available.

To provide a monetized estimate of the impacts of the proposed Regulations, the Department employed a standard form of cost-benefit analysis, where the costs and benefits of the proposed Regulations are assessed relative to a baseline forecast of emissions and economic growth (i.e. a forecast without the proposed Regulations). This means that both the costs and benefits of policies included in the baseline, such as the proposed Methane Regulations, and the sector’s emissions reduction activities that result from those policies, such as CCUS, are not included in the impacts reported in this analysis. The analysis of impacts is performed using a departmental economic model, as described in the “Analytical framework for the CBA” section below.

The baseline uses the most recent departmental reference case, which is based on the CER’s Current Measures production forecast and assumes existing policies and measures, such as carbon pricing, are in place as well as the forthcoming proposed Methane Regulations.

This cost-benefit analysis monetizes a subset of the total benefits to the environment of the proposed Regulations in the form of reduced GHG emissions. This benefit is estimated using the Government of Canada’s social cost of carbon (SCC), which is meant to be a comprehensive estimate of damages associated with the climate change caused by each tonne of greenhouse gas emissions. The SCC takes into account changes in agricultural productivity, adverse impacts on human health, property damages from increased flood risk, and increases in energy system costs. Each tonne of GHG (in CO2e) that is avoided has the benefit of avoiding its social cost of carbon.

Over the time frame of this analysis (2025 to 2032), the proposed Regulations are estimated to result in cumulative incremental GHG emissions reductions (i.e. beyond current policies and measures, including the proposed Methane Regulations) of 13.4 Mt. The value of these reductions is estimated to be $4.0 billion in avoided climate change induced global damages. The proposed Regulations are also estimated to have incremental impacts on the economy, which are estimated to be $3.3 billion plus administrative costs to industry and the Government of Canada estimated to be $219 million. Thus, the proposed Regulations are estimated to have net benefits of $428 million.

The analysis does not include a comprehensive inventory of all the impacts of the proposed Regulations. It does not account for the benefits from reduced air pollution. Higher order impacts related to jobs and associated economic activity from post-2032 investments in CCUS and other major decarbonization activities to reduce emissions from the sector are outside the scope of this analysis. The analysis does not fully consider the stimulation of new low-carbon industries, such as hydrogen, or for the longer-term competitiveness benefits of a decarbonized Canadian oil and gas sector in a world that complies with existing commitments under the Paris Agreement.

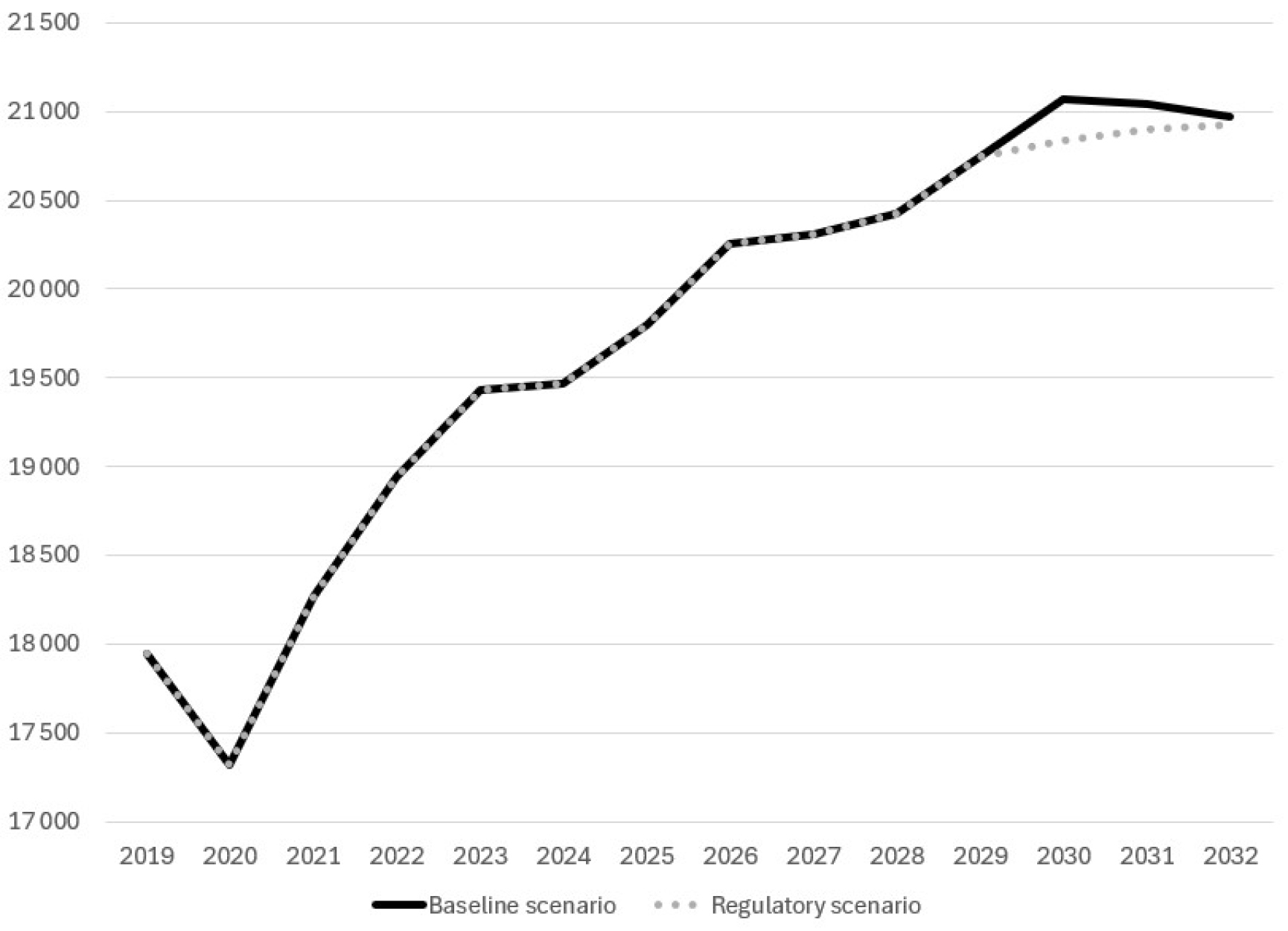

The costs in a CBA are the monetized costs of a regulation to Canadians relative to a baseline. In both the baseline and the regulatory scenarios, Canadian oil and gas production is projected to increase between 2019 and 2030: by about 17% in the baseline scenario and by almost the same (about 16%) in the regulatory scenario. The estimated costs of the proposed Regulations reflect the difference between these two projections.

In the model used for this CBA, these costs are assumed to be borne by Canadians. This is because the model assumes that Canadian households own the means of production. That is, Canadian households not only supply the labour, but are also assumed to own the capital used in production, as shareholders in the firms that produce goods and services. While this is a standard assumption in economic theory and modelling, in reality, many Canadian oil and gas firms are multi-national. For this reason, costs to Canadian society may be overestimated by assuming that all costs associated with lost profits are borne by Canadian households rather than being absorbed by multi-national firms and their shareholders.

Analytical framework for the CBA

To estimate the social value of the proposed Regulations, a cost-benefit analysis was conducted to account for the impacts on GHG emissions and the Canadian economy relative to the baseline for this analysis, while also accounting for the administrative costs for government and industry. These impacts were analyzed over a 7.5-year time frame, from mid-2025 to the end of 2032, which covers the period in which operators must register (the second half of 2025), through the end of the first compliance period in 2032. Capital costs are annualized over their expected life expectancy, and presented here as annualized costs, consistent with the presentation of operating costs and expected annual GHG reductions over the 2030 to 2032 period. Thus, the overall analysis underestimates the total lifetime costs and benefits attributable to actions taken in the first compliance period. However, this approach does provide a balanced perspective on the proportional costs and benefits of compliance. While the proposed Regulations would set the emissions cap indefinitely beyond the first compliance period, the policy intention is to review the trajectory of the emissions cap for future compliance periods within five years of the coming into force of the proposed Regulations to ensure the sector remains on a path to net-zero by 2050. The economic impacts of amending the emissions cap level for future compliance periods would be assessed at that time.

The analysis employs the Department’s multi-region, multi-sector, computable general equilibrium model (EC-Pro) of the Canadian economy to analyze the incremental impacts of the proposal relative to the baseline. This modelling framework differs from the energy systems model used to produce the departmental reference case. As a result of this difference in modelling frameworks, the projections in this analysis may vary slightly from the 2023 Departmental Reference Case (Ref23).footnote 2 More information on EC-Pro can be found in the “Modelling” section below.

The value of GHG emissions reductions is calculated using the Department’s social cost of greenhouse gases (SC-GHG) emissions. All dollar figures are presented in 2023 Canadian dollars and discounted at 2% annually (to 2025) when presented in present value form. This is the near-term Ramsey discount rate now utilized by the Government of Canada when monetizing GHG emissions reductions. More information on this approach is presented in the “Benefits” section.

Baseline scenario

The baseline scenario is a projection based on a modified Ref23. This includes federal, provincial, and territorial policies and measures that were in place as of August 2023, such as carbon pricing, the Clean Fuel Regulations, and investment tax credits. In addition, Ref23 was modified to include the proposed Methane Regulations which aim to achieve at least a 75% reduction in oil and gas sector methane emissions by 2030, relative to 2012 levels. The forecasts of oil and natural gas prices in Ref23 are taken from the Canada Energy Regulator’s 2023 Current Measures Scenario, as released in Canada’s Energy Future 2023. The model projects that under this scenario, Canadian oil and gas production will grow by 17% from 2019 to 2030, and that labour expenditure in the economy is estimated to grow by 18% and Canadian GDP is estimated to grow by 20% over this same time frame.

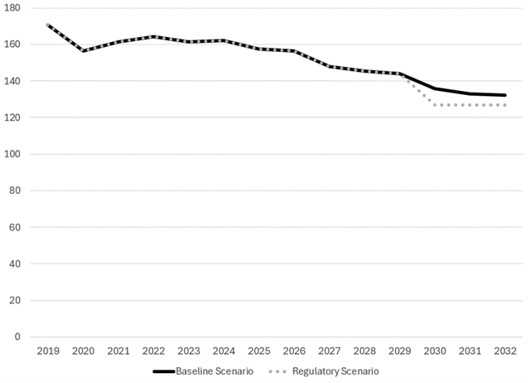

Emission intensities in the oil and gas industry are projected to decrease over time in the baseline scenario. These emission intensity improvements are expected to result from industry compliance with the regulations and measures currently in place, the proposed Methane Regulations, as well as other ongoing industrial efficiency improvements. These expected improvements lead to decreased GHG emissions over the time frame of analysis. These emissions intensity improvements are expected to result from the deployment of various emissions abatement technologies, including methane abatement technologies, increased use of solvents and carbon capture and storage, and increased use of hydrogen as a low-carbon source of energy. The average annual baseline emissions from the sector is estimated to be 134 Mt in CO2e in the first compliance period (2030 to 2032). That is, by the 2030 to 2032 period, the sector is estimated to reduce emissions by 22% below 2019 levels in the absence of the proposed Regulations.

Regulatory scenario

The regulatory scenario builds on the baseline scenario, with the assumption that the proposed Regulations are implemented.

The proposed Regulations would set a sector-wide emissions cap on covered emissions at 27% below 2026 reported emissions. The baseline scenario estimates the 2026 emissions to be 156.6 Mt, resulting in a modelled emissions cap of 114 Mt. In the model, allowances equal to the emissions cap level are allocated to subsectors each year from 2030 to 2032 based on 2019 emissions intensities and the forecasted in-year production in a given year. National historical emissions intensities used in the modelling were calculated and applied at an aggregation that is broadly consistent with the aggregation of distribution rates set out in the proposed Regulations.

Covered operators would be required to remit one eligible compliance unit for each tonne of GHGs emitted. Compliance units can include allowances, decarbonization units (up to 10% of a covered operator’s compliance obligation) and Canadian offset credits (up to 20% of a covered operator’s compliance obligation). The extent to which offsets would be used would depend on their price, which is currently uncertain. Therefore, offsets were not modelled as a compliance option in the central case. Given that it is expected that there will be offsets available and used, however, the “Sensitivity analysis” section discusses their potential use and impacts on emissions and production relative to the central case.