Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations: SOR/2022-138

Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 156, Number 13

Registration

SOR/2022-138 June 20, 2022

CANADIAN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ACT, 1999

P.C. 2022-723 June 17, 2022

Whereas, pursuant to subsection 332(1)footnote a of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999footnote b, the Minister of the Environment published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on December 25, 2021, a copy of the proposed Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations, substantially in the annexed form, and persons were given an opportunity to file comments with respect to the proposed Regulations or to file a notice of objection requesting that a board of review be established and stating the reasons for the objection;

Whereas, pursuant to subsection 93(3) of that Act, the National Advisory Committee has been given an opportunity to provide its advice under section 6footnote c of that Act;

And whereas, in accordance with subsection 93(4) of that Act, the Governor in Council is of the opinion that the proposed Regulations do not regulate an aspect of a substance that is regulated by or under any other Act of Parliament in a manner that provides, in the opinion of the Governor in Council, sufficient protection to the environment and human health;

Therefore, Her Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health, pursuant to subsection 93(1) of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 footnote b, makes the annexed Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations.

Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations

Definitions

Definitions

1 The following definitions apply in these Regulations.

- single-use plastic checkout bag

- means a plastic manufactured item, made entirely or in part from plastic, that is formed in the shape of a bag that is designed to carry purchased goods from a business and

- (a) whose plastic is not a fabric as defined in section 2 of the Textile Labelling Act; or

- (b) whose plastic is a fabric as defined in section 2 of the Textile Labelling Act that will break or tear if the bag is

- (i) used to carry 10 kg over a distance of 53 m 100 times, or

- (ii) washed in accordance with the washing procedures specified for a single domestic wash in the International Organization for Standardization standard ISO 6330, entitled Textiles — Domestic washing and drying procedures for textile testing, as amended from time to time. (sac d’emplettes en plastique à usage unique)

- single-use plastic cutlery

- means a plastic manufactured item, made entirely or in part from plastic, that is formed in the shape of a fork, knife, spoon, spork or chopstick and that

- (a) contains polystyrene or polyethylene; or

- (b) changes its physical properties after being run through an electrically operated household dishwasher 100 times. (ustensile en plastique à usage unique)

- single-use plastic flexible straw

- means a single-use plastic straw that has a corrugated section that allows the straw to bend and maintain its position at various angles. (paille flexible en plastique à usage unique)

- single-use plastic foodservice ware

- means a plastic manufactured item, made entirely or in part from plastic, that

- (a) is formed in the shape of a clamshell container, lidded container, box, cup, plate or bowl;

- (b) is designed for serving or transporting food or beverage that is ready to be consumed; and

- (c) contains expanded polystyrene foam, extruded polystyrene foam, polyvinyl chloride, a plastic that contains a black pigment produced through the partial or incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons or an oxo-degradable plastic. (récipient alimentaire en plastique à usage unique)

- single-use plastic ring carrier

- means a plastic manufactured item, made entirely or in part from plastic, that is formed in the shape of a series of deformable rings or bands that are designed to surround beverage containers in order to carry them together. (anneaux en plastique à usage unique pour emballage de boissons)

- single-use plastic stir stick

- means a plastic manufactured item, made entirely or in part from plastic, that is designed to stir or mix beverages or to prevent a beverage from spilling from the lid of its container. (bâtonnet à mélanger en plastique à usage unique)

- single-use plastic straw

- means a plastic manufactured item, made entirely or in part from plastic, that is formed in the shape of a drinking straw and that

- (a) contains polystyrene or polyethylene; or

- (b) changes its physical properties after being run through an electrically operated household dishwasher 100 times. (paille en plastique à usage unique)

Non-application

Transit

2 (1) These Regulations do not apply in respect of plastic manufactured items referred to in section 1 that are in transit through Canada, from a place outside Canada to another place outside Canada, and are accompanied by written evidence establishing that the items are in transit.

Export

(2) Subject to sections 8 and 9, these Regulations do not apply in respect of plastic manufactured items referred to in section 1 that are manufactured, imported or sold for the purpose of export.

Waste

(3) These Regulations do not apply in respect of plastic manufactured items referred to in section 1 that are waste.

Single-use Plastic Ring Carriers

Prohibition — manufacture or import

3 (1) A person must not manufacture or import single-use plastic ring carriers.

Prohibition — sale

(2) A person must not sell single-use plastic ring carriers.

Single-use Plastic Straws

Prohibition — manufacture or import

4 A person must not manufacture or import single-use plastic straws, other than single-use plastic flexible straws.

Prohibition — sale

5 (1) Subject to subsections (2) to (6), a person must not sell single-use plastic straws.

Exception — sale in certain settings

(2) A person may sell single-use plastic flexible straws in a non-commercial, non-industrial and non-institutional setting.

Exception — business to business sales

(3) A business may sell a package of 20 or more single-use plastic flexible straws to another business.

Exception — retail sales

(4) A retail store may sell a package of 20 or more single-use plastic flexible straws to a customer if

- (a) the customer requests straws; and

- (b) the package is not displayed in a manner that permits the customer to view the package without the help of a store employee.

Exception — beverage container

(5) A retail store may sell a single-use plastic flexible straw to a customer if the straw is packaged together with a beverage container and the packaging was done at a location other than the retail store.

Exception — sale in care institutions

(6) A hospital, medical facility, long-term care facility or other care institution may sell single-use plastic flexible straws to patients or residents.

Other Plastic Manufactured Items

Prohibition — manufacture or import

6 (1) A person must not manufacture or import single-use plastic checkout bags, single-use plastic cutlery, single-use plastic foodservice ware or single-use plastic stir sticks.

Prohibition — sale

(2) A person must not sell single-use plastic checkout bags, single-use plastic cutlery, single-use plastic foodservice ware or single-use plastic stir sticks.

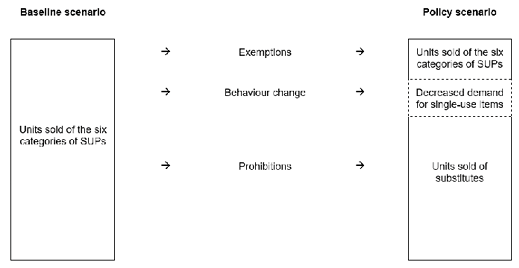

Analysis

Accredited laboratory

7 (1) For the purposes of these Regulations, any analysis performed to determine the physical characteristics of single-use plastic checkout bags, single-use plastic cutlery, single-use plastic flexible straws, single-use plastic foodservice ware or single-use plastic straws must be performed by a laboratory that meets the following conditions at the time of the analysis:

- (a) it is accredited

- (i) under the International Organization for Standardization standard ISO/IEC 17025, entitled General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories, by an accrediting body that is a signatory to the International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation Mutual Recognition Arrangement, or

- (ii) under the Environment Quality Act, CQLR, c. Q-2; and

- (b) subject to subsection (2), the scope of its accreditation includes the analysis of the physical characteristics of single-use plastic checkout bags, single-use plastic cutlery, single-use plastic foodservice ware, single-use plastic flexible straws and single-use plastic straws.

Standards of good practice

(2) If no method has been recognized by a standards development organization in respect of the analysis performed to determine the physical characteristics of the plastic manufactured items referred to in subsection (1) and the scope of the laboratory’s accreditation does not therefore include that analysis, the analysis must be performed in accordance with standards of good scientific practice that are generally accepted at the time that it is performed.

Record Keeping

Records — export

8 Any person that manufactures for the purpose of export, or that imports for the purpose of export, a plastic manufactured item to which these Regulations apply must keep records containing the following information and documents for each type of plastic manufactured item that was manufactured for the purpose of export or imported for the purpose of export:

- (a) in the case of a person that manufactures for the purpose of export,

- (i) the common or generic name and the trade name, if any, of the item,

- (ii) the quantity of the item manufactured at each manufacturing facility,

- (iii) the date of manufacture of the item,

- (iv) the date the item was exported and the quantity exported or, if it has not yet been exported, the date on which it is intended to be exported and the quantity intended to be exported, and

- (v) the name of the entity, if any, to which the item is sold in Canada for subsequent export; and

- (b) in the case of a person that imports for the purpose of export,

- (i) the common or generic name and the trade name, if any, of the item,

- (ii) the quantity imported of the item,

- (iii) the date the item was imported,

- (iv) the copies of the bill of lading, invoice and all documents submitted to the Canada Border Services Agency respecting the importation of the item,

- (v) the date the item was exported and the quantity exported or, if it has not yet been exported, the date on which it is intended to be exported and the quantity intended to be exported, and

- (vi) the name of the entity, if any, to which the item is sold in Canada for subsequent export.

Retention of records

9 (1) A person that is required to keep records under section 8 must keep the records at the person’s principal place of business in Canada or at any other place in Canada where they can be inspected, for at least five years after the date on which they are made. If the records are not kept at the person’s principal place of business, the person must provide the Minister with the civic address of the place where they are kept.

Records moved

(2) If the records are moved, the person must notify the Minister in writing of the civic address in Canada of the new location within 30 days after the day of the move.

Amendments to these Regulations

10 Subsection 2(2) of these Regulations is repealed.

11 Subsection 5(5) of these Regulations is repealed.

Related Amendment to the Regulations Designating Regulatory Provisions for Purposes of Enforcement (Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999)

| Item | Column 1 Regulations |

Column 2 Provisions |

|---|---|---|

| 38 | Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations |

|

Coming into Force

Six months after registration

13 (1) Subject to subsections (2) to (5), these Regulations come into force on the day that, in the sixth month after the month in which they are registered, has the same calendar number as the day on which they are registered or, if that sixth month has no day with that number, the last day of that sixth month.

One year after registration

(2) Subsection 3(1) comes into force on the first anniversary of the day on which these Regulations are registered.

Eighteen months after registration

(3) Section 5 and subsection 6(2) come into force on the day that, in the 18th month after the month in which these Regulations are registered, has the same calendar number as the day on which they are registered or, if that 18th month has no day with that number, the last day of that 18th month.

Two years after registration

(4) Subsection 3(2) and section 11 come into force on the second anniversary of the day on which these Regulations are registered.

Forty-two months after registration

(5) Section 10 comes into force on the day that, in the 42nd month after the month in which these Regulations are registered, has the same calendar number as the day on which they are registered or, if that 42nd month has no day with that number, the last day of that 42nd month.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: Current scientific evidence indicates that macroplastic pollution poses an ecological hazard, including physical harm, to some animals and their habitat. Canadians use substantial quantities of single-use plastic manufactured items (SUPs) every year. These SUPs are designed to be discarded once their single use has been fulfilled. A share of that waste becomes plastic pollution. Action is needed to restrict or eliminate SUPs that pose a threat of harm to the environment.

Description: The Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations (the Regulations) will prohibit the manufacture, import and sale (including for the purpose of export) of six categories of SUPs (i.e., checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, ring carriers, stir sticks and straws), with a temporary exemption for export. The Regulations also provide exemptions for SUP flexible straws to accommodate persons with disabilities. Since SUP checkout bags, SUP cutlery and SUP straws have reusable substitutes made of plastics, the Regulations identify performance standards to differentiate between single-use and reusable items for these three product categories.

For SUP checkout bags, SUP cutlery, SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, SUP stir sticks, and SUP straws, the prohibitions on manufacture and import will come into force six months after the Regulations are registered. The prohibition on sale for these items will come into force 18 months after the Regulations are registered. SUP flexible straws will not be subject to the prohibition on manufacture and import as there is a need to ensure supply of these items for people who need them, but their sale will be subject to special rules that will come into force 18 months after registration. The prohibition on the manufacture and import of SUP ring carriers will come into force 12 months after the Regulations are registered. The prohibition on sale for SUP ring carriers, as well as the repeal of a temporary exemption on the sale of SUP flexible straws packaged together with beverage containers, will come into force 24 months after the Regulations are registered. The Regulations will also repeal the temporary exemption on manufacture, import and sale for the purposes of export for all categories of SUPs 42 months after the Regulations are registered.

Rationale: Plastics are among the most universally used materials in modern society. Single-use consumer items are the most commonly collected items in litter clean-ups, with plastic being the most common material recovered in both domestic and international clean-up efforts. The six categories of SUPs subject to the Regulations represented an estimated 150 000 tonnes sold in 2019 or an estimated 3% of the total plastic waste generated in Canada in 2019.

The Regulations support the federal, provincial, and territorial governments’ Strategy on Zero Plastic Waste (PDF). Several provincial, territorial and municipal jurisdictions have already enacted prohibitions or standards for certain SUPs. On October 7, 2020, the Department of the Environment (the Department) published a discussion paper on the Canadian Environmental Protection Act Registryfootnote 2 outlining a proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution. During the ensuing 60-day public comment period, the Department received 205 written submissions representing the views of 245 stakeholder groups (151 industry members; 39 provincial, territorial, or municipal governments; two Indigenous groups; 32 non-governmental organizations; and 21 other groups such as think tanks, health advocacy and taxpayer groups). In addition, the Department received over 24 000 emails from individual Canadians, as well as an online petition started by a civil society group that received over 100 000 signatures indicating support for government action.

The proposed Regulations were published in Canada Gazette, Part I on December 25, 2021, followed by a 70-day public consultation period. During this consultation period, stakeholders and members of the public were given an opportunity to provide the Department with written comments on the proposed Regulations. The Department received 146 written submissions (75 industry members; 22 provincial, territorial or municipal governments; one Indigenous group; 29 non-governmental organizations (NGOs); and 19 others). The Department also received 25 notices of objection on the proposed Regulations and requests to establish a board of review to inquire into the nature and extent of the danger posed by one or more of the six categories of SUPs targeted by the Regulations. The Minister of the Environment has declined to form a board of review. All notices of objection, along with the Minister’s response letters, are available on the CEPA Registry.

Overall, NGOs and local governments have expressed support for the Regulations while resin producers and plastic product manufacturers have raised concerns. Other industry stakeholders have begun transitioning away from using SUPs or have announced their intention to do so. Support for the Regulations from provincial and territorial governments has been mixed.

In addition to written comments, the Government held online meetings with stakeholders to answer questions and receive feedback. As of March 11, 2022, a total of 48 online meetings with stakeholders took place, including 27 businesses, 12 industry associations and their members, four environmental non-governmental organizations, four municipal and provincial governments, and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. In addition, the Department met with all provinces and territories via the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Many meetings involved multiple stakeholders and included representatives from Health Canada. During these meetings, stakeholders were given opportunities to pose questions and provide feedback. A survey was also sent to a large number of manufacturers across Canada seeking input on the impacts to the manufacturing sector, with 12 responses received.

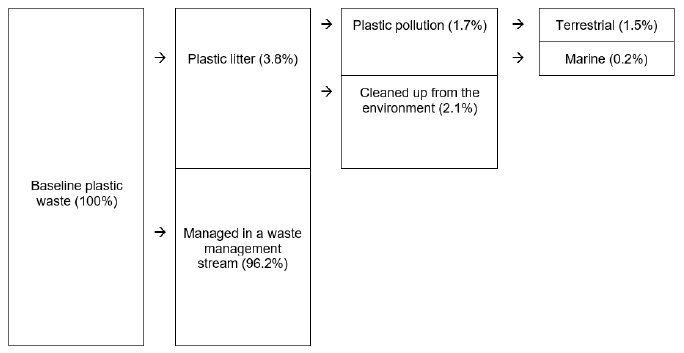

The Regulations are expected to result in a net decrease of approximately 1.3 million tonnes in plastic waste over the 10-year analytical period (2023 to 2032), which represents around 3% of the total estimated plastic wastefootnote 3 generated in Canada each year. They are also expected to result in a decrease of around 22 000 tonnes in plastic pollutionfootnote 4 over the same period, which represents around 5% of the total plastic pollution generated each year. The Regulations are expected to result in $2 billion in present value costs over the analytical period, stemming mainly from substitution costs. While these costs are significant in aggregate, they will be widely dispersed across Canadian consumers (around $5 per capita per year). The prohibitions on manufacture of the six categories of SUPs are also expected to result in $176 million in costs to Canadian manufacturers over the analytical period.

By reducing plastic pollution, the Regulations are also expected to reduce the risk of ecological harm to wildlife and their habitats, as well as increase Canadians’ enjoyment of nature. While these benefits are not monetized in this analysis, they are expected to be significant, given the harms associated with plastic pollution. The analysis did monetize benefits associated with avoided costs for terrestrial litter clean-up and avoided marine plastic pollution ($616 million in present value monetized benefits over the analytical period).

Issues

The Canadian economy generates large amounts of plastic waste every year, of which a certain proportion enters the environment as plastic pollution. Current scientific evidence indicates that macroplastic pollution causes physical harm to wildlife on an individual level and has the potential to adversely affect habitat integrity. Single-use plastic manufactured items (SUPs) are significant contributors to plastic pollution, as they are designed to be discarded once their single use has been fulfilled. Preventing pollution and waste is an important shared jurisdiction among all levels of government in Canada, and plastic pollution is an issue with national and international dimensions that cannot be effectively eliminated through provincial, territorial, or local measures alone. Therefore, the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health (the Ministers), in accordance with section 93 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA or “the Act”), recommended that the Governor in Council eliminate or restrict six categories of SUPs subject to the Regulations. These categories of SUPs are the following: checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, ring carriers, stir sticks, and straws (hereafter referred to as the “six categories of SUPs”).

Background

Lifecycle of plastic manufactured items in the Canadian economy

Plastics are among the most universally used material in modern society. Plastics are low-cost, durable and are used in a wide range of applications, such as packaging, construction materials, automotive materials, electronics, textiles, and medical equipment. Plastics can be created from a wide range of synthetic, or semi-synthetic organic compounds and are formed from long-chain polymers of high molecular mass that often contain chemical additives. Different polymers can be manufactured using different compositions of petroleum products, plant-based starting material, or recycled and recovered plastics. Plastic manufactured items can be formed into a specific physical shape, or design during manufacture and serve many different functions. They can include final products, as well as components of products. The scientific literature often categorizes plastic pollution by size, in an environmental context. Individual pieces of plastic that are less than or equal to 5 millimetres (mm) in size are referred to as microplastics, while those that are greater than 5 mm in size are referred to as macroplastics. Microplastics can be “primary microplastics” (intentionally produced micro-sized plastic particles), or “secondary microplastics” (micro-sized plastic particles resulting from the breakdown of larger plastic manufactured items).

The proper management of plastic manufactured items is a global issue as millions of tonnes of plastics are produced each year around the world and because plastic pollution entering the oceans is transported long distances to other parts of the globe. It is estimated that half of the plastics produced each year are for single-use items.footnote 5 In 2020, 367 million tonnes of plastic were produced globally, a 0.3% decrease from 2019.footnote 6 The COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered economic activity and demand patterns, in some cases increasing consumption of SUPs (e.g., supplied with restaurant takeout) and plastic packaging (due to the growth of e-commerce). It has also reduced plastic consumption in other economic sectors such as wholesale and retail trade, motor vehicle manufacture, and construction.footnote 7

In order to better understand the quantities, uses, and end-of-life management of plastics in the Canadian economy, the Department of the Environment (the Department) commissioned the Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste (the 2019 Deloitte Study). This study published in 2019 presented the first detailed characterization of physical flow of plastic material in the Canadian economy. Building on and refining this work, Statistics Canada has since released its physical flow account for plastic material, which describes the production and fate of plastic in the Canadian economy.

Statistics Canada estimated that approximately 6.3 million tonnes of plastic resins (raw materials) were introduced to the domestic market in 2018 while approximately 4.4 million tonnes of plastic manufactured items became plastic waste. The packaging sector alone accounted for 50% (approximately 2.2 million tonnes) of all plastic waste generated, as the vast majority of packaging is designed to become waste after fulfilling a single-use. Of the 4.4 million tonnes of plastic waste generated nationally in 2018, 3.9 million tonnes (87%) were landfilled or incinerated without energy recovery, 365 000 tonnes (8%) were recycled, 149,000 tonnes (4%) were incinerated with energy recovery, and 43 000 tonnes (1%) became plastic pollution. Using those numbers, Canadians produced around one kilogram of plastic pollution per capita in 2018.

These figures support findings of the 2019 Deloitte Study that the Canadian plastics economy is mostly linear, as opposed to circular. Under a linear economy, plastic manufactured items follow a unidirectional path: production from mostly virgin (as opposed to recycled) materials, usage (until no longer deemed useful) and then disposal into the waste stream, mostly for landfill. Put another way, most plastic manufactured items in a linear economy are produced from virgin resins, and their value is not recovered at the end of their useful life. Therefore, most of the plastic waste generated in Canada enters landfills and exits the economy, representing a significant lost potential economic opportunity.

By contrast, a circular economy is a model of production and consumption that recovers and restores products, components, and materials through strategies like reuse, repair, remanufacture or (as a last resort) recycling.footnote 8 Under a circular economy, plastic manufactured items are produced by a number of different pathways, one of which includes using recycled resins. Their values are recovered at the end of their useful life to be reintegrated into the economy. In this way, the end of the value chain for one manufactured item becomes the start of the value chain for another, thereby extending life cycles and reducing waste.

There are many factors contributing to the linear nature of the plastics economy in Canada, including the following:

- virgin and recycled plastic resins compete: competition is difficult for the recycling industry because of inconsistent feedstock composition and a more labour-intensive cost structure compared to virgin resin production, which can take advantage of economies of scale;

- weak end-markets for recycled plastics: in some cases, recycled resins are a cheaper substitute for product manufacturers, but the inconsistent supply of quality feedstock at a competitive price undermines the establishment of viable and lasting end-markets;

- collection rates are low: only 25% of plastics are collected and sent to a sorting facility in Canada, according to the 2019 Deloitte Study (through curbside collection, recycling depots, or deposit-refund systems), while only around a third of collected plastics are effectively recycled because of contamination, infrastructure deficiencies and lack of end-markets;

- insufficient recovery options: current near absence of high-volume recovery options, losses from existing processes and competition from low-cost disposal substitutes, such as landfills, point to the need for investments in innovation and infrastructure, in particular to commercialize and scale up new technologies; and

- cost of plastic pollution is shouldered by individuals and communities: the responsibility for preventing and managing land-based sources of plastic pollution, such as urban and roadside litter, is largely shouldered by municipalities, civil society organizations and volunteers, at a great cost.

The 2019 Deloitte Study estimated that 2 500 tonnes of the plastic waste generated in Canada in 2016 entered the oceans as plastic pollution, while no estimates of the amount of plastic pollution entering Canadian freshwaters (e.g., the Great Lakes, other lakes, rivers) but never reach the oceans currently exists. Internationally, academic studies have estimated the total amount of plastic pollution entering oceans globally at between 8 million tonnes and 13 million tonnes per year.footnote 9 In fact, plastics constitute the most prevalent type of litter found in the oceans, estimated to make up at least 80% of total marine debris (from surface waters to deep-sea sediments), plastic bags being among the most prevalent littered items.footnote 10

The 2019 Deloitte Study indicates that one of the key pathways for plastic waste to become terrestrial or marine plastic pollution is people dropping litter on the ground or directly into aquatic environments. An estimated 80% of all marine plastic pollution originates on land and is transported to the ocean via wind or rivers, with the remaining 20% attributable to fishing activities, natural disasters, and other sources.footnote 11 Once plastic pollution reaches oceans, the majority will slowly weather and fragment into microplastics, accumulate on shorelines, sink to the seabed, or float on the sea surface, but will never fully decompose.

Plastic pollution is found on the shorelines of every continent, with greater proliferation typically found near tourist destinations and densely populated areas. Large-scale marine and freshwater litter clean-ups are very costly, and therefore, limited in practice. While such clean-ups may result in temporary benefits, they do not alter the inflow of plastic pollution into marine or freshwater environments, and must therefore be frequently repeated for sustained benefits to be realized. For this reason, preventing plastic pollution from entering the environment in the first place is often seen as the only viable approach to successfully managing the issue of marine plastic pollution on a long-term basis.footnote 11

Science Assessment of Plastic Pollution

In October 2020, the Department of the Environment and the Department of Health published a Science Assessment of Plastic Pollution (the Science Assessment) on the Canada.ca (Chemical Substances) website. The intent of the Science Assessment was to summarize the current state of the science regarding the potential impacts of plastic pollution on the environment and human health, as well as to inform future decision-making on plastic pollution in Canada. The Science Assessment found that macroplastic and microplastic pollution are ubiquitous in the environment. The Science Assessment also found that many sources of release contribute to plastic pollution, and that the potential effects of microplastics on individual animals, the environment, and human health are unclear and require more research.

With respect to macroplastic pollution, the Science Assessment found evidence of adverse effects, including mortality, to some animals through:

- entanglement, which can lead to suffocation, strangulation, or smothering;

- ingestion, which can block airways or intestinal systems leading to suffocation or starvation; and

- transport of invasive species into well-established ecosystems or transport of diseases that can alter the genetic diversity of an ecosystem when they use the plastic pollution as a vessel for rafting.

Overall, the Science Assessment recommended pursuing immediate action to reduce the presence of plastic pollution in the environment, in accordance with the precautionary principle as defined in section 2 of CEPA.

Government action on plastic waste and plastic pollution

The Government of Canada has committed to taking action to reduce plastic waste and plastic pollution through several avenues. In November 2018, through the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, the federal, provincial and territorial governments approved, in principle, a Canada-wide Strategy on Zero Plastic Waste (PDF)(the Strategy). The Strategy takes a circular economy approach to plastics and provides a framework for action in Canada. Federal, provincial and territorial governments are collaborating to implement the Action Plan on Zero Plastic Waste (the Action Plan), for which Phase 1 (PDF) and Phase 2 (PDF) were approved in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

In October 2020, the Government published a discussion paper entitled A proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution (the Discussion Paper). The Discussion Paper outlined a proposed integrated management approach that addresses the entire life cycle of plastics to prevent plastic waste and plastic pollution. The Government described a suite of measures to be developed under CEPA to implement the integrated management approach, which seeks to:

- manage single-use plastics using a management framework;

- establish performance standards for plastic products to reduce (or eliminate) their environmental impact and stimulate demand for recycled plastics; and

- ensure end-of-life responsibility, so that companies that manufacture or import plastic products or sell items with plastic packaging are responsible for collecting and recycling them.

Based on the findings of the Science Assessment and other available information, the Ministers were satisfied that plastic manufactured items met the ecological criterion for a toxic substance as set out in paragraph 64(a) of CEPA. In order to develop risk management measures under CEPA to address the potential ecological risks associated with certain plastic manufactured items becoming plastic pollution, the Administrator in Council made an Order adding plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1 to CEPA, which was published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on May 12, 2021. The listing enables the Ministers to propose risk management measures under CEPA that could target the sources of plastic pollution and change behaviour at key stages in the life cycle of plastic products, such as product design, manufacture, use, disposal, and value recovery.

Most prevalent items contributing to plastic pollution

Internationally, single-use consumer items are the most commonly picked up items in litter clean-ups, with plastic being the most common material recovered. Most of the top 10 items reported in the Ocean Conservancy International Coastal Cleanup 2020 report (in which Canada participated) were made out of or contained plastics. These items included food wrappers, cigarette filters, plastic beverage bottles, other unspecified trash, plastic bottle caps, plastic grocery bags, straws, stir sticks, and plastic take-out containers. Similarly, data based on total items collected over time from the European Environment Agencyfootnote 12 shows that the most common category of items found as marine litter on the beach are cigarette filters, plastic caps and drink lids, shopping bags, string and cord, food wrappers, cotton bud sticks, drink bottles, and food containers. On a per material basis, plastic was found to account for 87% of all materials collected over time.footnote 13

Domestically, the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup has also typically found cigarette filters, food wrappers, bottle caps, plastic bags, plastic bottles, and straws among its 10 most commonly collected litter items. While quantities collected in the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup were lower in 2020, mainly due to COVID-19 limiting participation, the quantity collected in 2019 represented almost double the quantity for 2017 by weight. Other plastic items commonly found in shoreline clean-ups include cutlery, ring carriers, cups, pieces of foam and plastic fragments, and personal hygiene products.

Despite differences in the number of items recovered in each item category, some item categories are considered more environmentally problematic, as more harmful to wildlife or the environment in general based on material, weight and shape, or structure. Of common consumer items made of plastic, plastic bags pose one of the greatest impacts on marine wildlife.footnote 14 Plastic bags are lightweight and usually have looped handles that can entangle wildlife. Ring carriers can also pose a threat of entanglement due to their looped structure. Plastic bags and utensils have been rated the plastic items of greatest risk for ingestion by seabirds, turtles, and marine mammals.footnote 14 Many of the consumer items frequently picked up in litter clean-ups are also considered to be value recovery problematic as they are made of problematic plastics that have very low recycling rates.

Government action with respect to single-use plastic manufactured items

In June 2019, the Prime Minister announced a commitment for the Government of Canada to take steps to reduce plastic waste and plastic pollution, including working with provinces and territories to introduce standards and targets that would make companies that manufacture plastic products or that sell items with plastic packaging responsible for their plastic waste. In the same announcement, the Prime Minister committed the Government of Canada to banning harmful SUPs as early as 2021, where warranted and supported by scientific evidence. This commitment was reconfirmed in the 2019 Mandate Letter and the 2021 Mandate Letter to the Minister of the Environment (the Minister), as well as in the Speech from the Throne in September 2020.

In order to determine which SUPs are considered harmful and warrant prohibition in Canada, the Department developed a management framework for categorizing SUPs (the Framework), as presented in the Discussion Paper. The Framework categorized a wide selection of SUPs commonly collected as litter or flagged by other jurisdictions (e.g. different types of bags, different types of packaging, cigarette filters, coffee pods) as either environmentally problematic, value-recovery problematic, or both. The Science Assessment provides the justification to take action. As outlined in the Discussion Paper, further consideration was given to which SUPs should be included in the Regulations. The SUPs that were selected for the ban must meet the environmentally problematic and value-recovery problematic criteria using scientific evidence to assess environmental prevalence and value recovery challenges, with consideration for exemptions for certain essential functions. After evaluating the wide selection of SUPs in this way, the Framework identified six harmful SUPs, or categories of SUPs identified by utility, warranted for prohibition or restriction in Canada.

Checkout bags. Also known as shopping bags, grocery bags, or carryout bags. These items are typically given to customers at the retail point of sale to carry purchased goods from a business. They are typically (but not exclusively) made from high- or low-density polyethylene film and may, or may not have handles. SUP checkout bags have low recycling rates (estimated at less than 15%) despite being accepted in several recycling programs across Canada and are known to hamper recycling systems by becoming caught up in sorting and processing machinery. They are some of the most common forms of plastic litter in the natural environment (e.g., 31 164 units were collected from Canadian shorelines in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). Checkout bags have been identified by experts as posing a threat of entanglement, ingestion and habitat disruption for marine wildlife;

Cutlery (knives, forks, spoons, sporks and chopsticks). These items are typically given to customers by restaurants and other food vendors to eat quick-service, or takeout food, though they can also be purchased in bulk at many retail businesses such as grocery, or dollar stores. They are typically (but not exclusively) made from polypropylene or polystyrene. SUP cutlery has low recycling rates (estimated at close to 0%) and is typically not accepted in provincial or municipal recycling systems. It is a common form of plastic litter (e.g., 10 772 units were collected from Canadian shorelines in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). Cutlery litter has been ranked as a threat to wildlife because it is frequently encountered in the environment, carries food residues that encourage ingestion, and has rigid properties that make it hazardous harmful (e.g., by perforating organs) once eatenfootnote 15;

Foodservice ware made from, or containing problematic plastics. This category includes clamshell containers, lidded containers, cartons, cups, plates and bowls used for serving or transporting prepared food or beverages (i.e. that is ready to be consumed without any further preparation, such as cooking, boiling or heating). This category of SUPs only includes those made from problematic plastics, which are defined as extruded or expanded polystyrene foam, polyvinyl chloride, oxo-degradable plastics, or plastics that contain the additive “carbon black.” When littered in the environment, foodservice ware may be placed in a range of categories, depending on the kind of plastic used (e.g. expected to form part of the total units collected under the categories of foam [24 213 units], food wrappers/containers [74 224 units], or tiny pieces of plastic or foam [595 227 units] in the 2019 Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). Foodservice ware in the form of expanded polystyrene containers, takeout containers, cups and plates and plastic food lids have all been ranked as high by experts in terms of the threat posed to wildlife due to contamination and, for polystyrene foam, ingestion;

Ring carriers (typically known as six-pack rings). Ring carriers are deformable bands that are placed on beverage containers (e.g., cans, bottles) to package them for transport. They can be cut to hold different multiples of containers (e.g., two-packs, eight-packs). They are typically made from low-density polyethylene. Ring carriers are not typically recycled in Canada and are not accepted by provincial or municipal recycling systems. Ring carriers are a common form of plastic litter (e.g. 1 627 units collected from Canadian shorelines in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup) and are recognized as posing a threat of entanglement for wildlife such as seabirds;

Stir sticks (also known as stirrers or beverage stirrers). Stir sticks are typically made from polypropylene or polystyrene. They can be in the shape of a stick, rod, or tube, and can also have decorative elements (e.g., for cocktail stir sticks or muddlers) or have attachments to close coffee cup lids. They have very low or no recycling rates and are not typically accepted in provincial or municipal recycling systems. Stir sticks are found as litter in the environment. They are typically categorized alongside straws (e.g., stir sticks form part of the 26 157 units collected in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup referenced below for straws). Stir sticks pose the same threats to wildlife as straws; and

Straws. Straws are typically given to customers at restaurants, coffee shops, and other food vendors along with purchased drinks. They are typically (but not exclusively) made from polypropylene and have varying physical dimensions. They may also be sold in packages of multiple straws at retail locations such as grocery stores and dollar stores or may be packaged with another product (e.g., a juice box). Plastic straws are prevalent in litter data (e.g., 26 157 units of straws and stir sticks collected in Canada in 2019 through the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup). They have low or nil recycling rates due to their size and shape and are not typically accepted in provincial or municipal recycling systems. Straws are also ranked high by experts in terms of the threat posed to wildlife in the environment. They pose a threat of harm through ingestion (e.g., perforating organs).

Provincial, territorial and municipal actions on SUPs

Several municipal and provincial jurisdictions have already implemented bans on a selection of these six categories of SUPs. For example, in 2019, Prince Edward Island implemented bans on SUP checkout bags, and in 2020, Newfoundland and Labrador also implemented bans on SUP checkout bags. The bans permit businesses to offer paper and reusable checkout bags. Only Prince Edward Island mandates minimum fees for offering substitute checkout bags. All three of these bans also prohibit compostable and oxo-degradable SUP checkout bags and include various exemptions. In May of 2021, Yukon’s Speech from the Throne signalled the territory’s intention to ban SUPs and as of January 2022, all SUP shopping bags are banned in the territory. As of February 2022, no other SUP bans have been enacted at the provincial or territorial level, although British Columbia published a framework to facilitate municipal bans and amended its environmental protection legislation to allow it to develop province-wide bans.footnote 16 Numerous municipal governments have implemented SUP bans on a local level. For instance, Vancouver, Montréal, Sherbrooke, and several smaller municipalities across Canada have implemented bans on SUP checkout bags. Edmonton recently announced plans to regulate single-use shopping bags, polystyrene foam foodservice ware, utensils, straws, single-use cups, prepackaged condiments, and napkins.

Select Canadian market characteristics

According to the 2019 Deloitte Study, Canadian plastic product manufacturing (including SUPs and durable goods) accounted for $25 billion in sales in 2017. The study estimated that plastics manufacturing establishments were mainly located in Ontario (44%), Quebec (28%), British Columbia (11%), and Alberta (8%). Information from Statistics Canada indicates that domestic plastics manufacturers met approximately 50% of domestic demand, while imports met the remaining 50%.footnote 17 It is estimated that the United States receives 90% of Canadian exports, and provides over 60% of Canadian imports.

Distribution among the six categories of SUPs

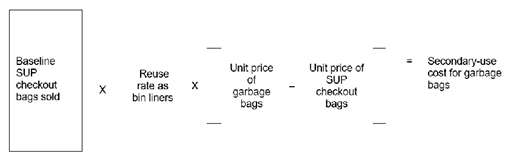

As shown in Table 1, the six categories of SUPs accounted for approximately $760 million in sales in 2019 or nearly 30 billion units sold. Per capita per day, these values translate to approximately $0.06 in sales and 2.2 units sold. Assuming that each unit sold fulfilled its single use in short order following its sale, the mass of each unit sold promptly became plastic waste. Based on this assumption, the six categories of SUPs generated approximately 150 000 tonnes of plastic waste, representing roughly 4% of the total plastic waste generated in Canada in 2019.footnote 18

| Category of SUP table b1 note b | Sales volume (in millions of units) |

Average annual growth (2015 to 2019, by volume) | Unit price (2021 dollars) | Value (in millions, 2021 dollars) |

Unit weight (grams) | Tonnage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUP checkout bags | 15 593 | 2.5% | $0.03 | $429 | 8 | 124 746 |

| SUP cutlery | 4 612 | 2.0% | $0.04 | $170 | 2.4 | 11 112 |

| SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics table b1 note d | 469 | 0.9% | $0.09 | $43 | 19.0 | 8 685 |

| SUP ring carriers | 183 | 1.9% | $0.03 | $6 | 3.5 | 648 |

| SUP stir sticks | 2 950 | 3.1% | $0.01 | $31 | 0.6 | 1 770 |

| SUP straws | 5 846 | 2.7% | $0.01 | $81 | 0.4 | 2 339 |

| Total (or weighted average) table b1 note c | 29 654 | 2.5% | $0.03 | $760 | 5.0 | 149 300 |

Table b1 note(s)

|

||||||

Significant progress has been made in recent years by governments and industry globally to phase out several commonly identified SUPs, especially SUP checkout bags, as described in the Global Commitment 2021 Progress Report published by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In Canada, some major companies have announced or have already implemented actions to reduce certain SUPs. For example, several companies in the quick-service restaurant industryfootnote 19,footnote 20,footnote 21 have already eliminated SUP straws and other SUPs in their Canadian establishments. Some full-service restaurants have also committed to eliminating all SUP straws from their restaurants.footnote 22 In the retail space, many grocery chains and other retailers have eliminated or have committed to eliminating SUP checkout bags from their stores.footnote 23,footnote 24,footnote 25 Despite the voluntary actions of some Canadian companies to reduce plastic waste in their establishments, consumption of the six categories of SUPs nationally is projected to grow at a positive rate for the next decade and beyond in the absence of regulatory intervention.

Substitutes to the six categories of SUPs

Substitutes for the six categories of SUPs exist and are readily available within established markets in Canada. Many of these substitutes are single-use manufactured items that are not made from plastics (single-use non-plastic manufactured items, or SUNPs). Most SUNPs are made from paper or wood, and as such, are typically heavier and costlier than their SUP counterparts. Regardless, SUNPs have become more prevalent in the market over time, as consumer preference for a substitute to SUPs grows with increased awareness of the impacts of plastic waste and plastic pollution. In the case of SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics and SUP ring carriers, substitutes exist that are also plastic manufactured items, but which do not pose the same environmental or value-recovery challenges. The estimated year-over-year market growth of most substitutes for the six categories of SUPs is higher than that of their SUP counterparts. As shown in Table 2, the average annual growth rate from 2015 to 2019 across a selection of readily available single-use substitutes to the six categories of SUPs was 4.7%.

| Category of SUP | Readily available single-use substitute material | Sales volume (in millions of units) |

Average annual growth (2015 to 2019, by volume) | Unit price (2021 dollars) | Value (in millions, 2021 dollars) |

Unit weight (grams) | Tonnage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUP checkout bags | paper | 3 709 | 4.8% | $0.08 | $292 | 52.6 | 214 562 |

| SUP cutlery | wood | 1 115 | 2.8% | $0.09 | $100 | 1.5 | 1 680 |

| SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics | paper and moulded fibre | 486 | 2.0% | $0.16 | $78 | 39.1 | 18 744 |

| aluminum | 238 | 0.3% | $0.14 | $33 | 9.5 | 2 262 | |

| SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics table b2 note d | recyclable plastics | 483 | 3.5% | $0.11 | $51 | 24 | 11 598 |

| SUP ring carriers | paper and moulded fibre | 127 | 2.7% | $0.30 | $39 | 27.6 | 3 502 |

| recyclable plastics | 53 | 1.6% | $0.14 | $8 | 19.5 | 1 034 | |

| plastic film table b2 note b | - | - | $0.06 | - | 18 | - | |

| SUP stir sticks | wood | 1 022 | 3.8% | $0.01 | $13 | 1.9 | 1 941 |

| SUP straws | paper | 744 | 13.0% | $0.03 | $21 | 0.8 | 595 |

| Total (or weighted average) table b2 note c | 7 976 | 4.7% | $0.08 | $634 | 29.7 | 255 918 | |

Table b2 note(s)

|

|||||||

Other substitutes to the six categories of SUPs are reusable manufactured items, made from a variety of materials including durable plastics, metals, woods, glass, silicone, and fabrics. Unlike single-use items, reusable items are specifically designed to remain durable through repeated uses and machine washings. Reusable items are typically heavier and costlier than their SUP, or SUNP counterparts, given their need for durability and associated quantity of raw material needed for their production. However, since a reusable item can be used multiple times, it essentially replaces a stream of single-use items over its useful lifetime, and if durable enough will eventually “meet or beat” the total cost of the stream of single-use items it diverted over time. How long it takes to break even depends on the price of the reusable item, the price of the single-use items it diverted, and the rate and duration of reuse.

With respect to the six categories of SUPs, the most commonly used reusable substitute is reusable checkout bags. Many Canadians have shifted their consumer behaviour to normalize bringing reusable checkout bags to a variety of retail settings, especially grocery stores. Some retail locations also sell reusable checkout bags at their checkout counters. Substituting reusable checkout bags for SUP checkout bags is more common in Canada than using substitutes for the five other categories of SUPs. For example, it is not yet common for consumers to bring reusable foodservice ware and reusable cutlery to collect and consume take-out food. Accordingly, reusable items are not seen to play as significant a role in diverting the consumption of five of the six categories of SUPs in the short term, relative to the role that SUNP and other single-use substitute items play in that regard. However, as ongoing education campaigns by governments and civil society groups increase awareness of waste and pollution caused by the consumption of single-use items, adoption of low-waste consumer behaviours may lead to more widespread preference for reusable products.

Public opinion research

A strong majority of Canadians are concerned about plastic pollution and that they are supportive of further action by governments. In a survey conducted by Abacus Data in 2018, 88% of respondents said they were concerned about plastic pollution in oceans and waterways, including 36% who say it is one of the most important environmental issues today.footnote 26 A major polling effort conducted by Ipsos in 2019 surveyed nearly 20 000 adults from 28 countries, showing widespread global support for action on plastics.footnote 27 Across all surveyed countries, 71% of respondents agreed with the statement that single-use plastics should be banned as soon as possible (by country, 72% of Canadian respondents and 57% of American respondents agreed with the statement).

The COVID-19 pandemic altered public opinion on SUPs bans and consumption of SUPs. Two surveys conducted by Dalhousie University, one pre-pandemic and another during, reported that support for a ban of all SUP food packaging fell from 72% of respondents in 2019 to 58% of respondents in 2020.footnote 28 The surveys also suggested that consumption habits changed, as 29% of respondents indicated that they were buying more plastic-packaged goods during the pandemic relative to before the pandemic. Conversely, over 90% of Canadians polled in a 2021 survey are concerned about the impact plastic pollution has on our oceans and wildlife and polling by Abacus Data in June 2020 reveals that 86% of Canadians support a ban on some SUPs which is up from 81% in 2019. In an early 2021 survey by Abacus Data commissioned by Oceana Canada, two-thirds of Canadians polled indicated support for extending the prohibitions to cover more than just the six categories of SUPs identified by the Framework, such as cigarette filters, polystyrene and other types of drink cups containing plastics.footnote 29

Objective

The objective of the Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations (the Regulations) is to prevent plastic pollution by eliminating or restricting the manufacture, import and sale (including for the purposes of export) of six categories of SUPs that pose a threat to the environment.

Description

The Regulations will eliminate, or restrict six categories of SUPs in Canada and are made pursuant to section 93 of CEPA.

Applicability

The Regulations will apply to the following categories of plastic items:

SUP checkout bags, which are plastic manufactured items made entirely or in part from plastic, formed in the shape of a bag, designed to carry purchased goods from a business, and typically given to a customer at the retail point of sale;

SUP cutlery, which encompasses plastic manufactured items made entirely or in part from plastic and formed in the shape of a knife, fork, spoon, spork, or chopstick;

SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, which encompasses plastic manufactured items made entirely or in part from plastic and:

- formed in the shape of a clamshell container, lidded container, box, cup, plate, or bowl,

- designed for serving or transporting food or beverage that is ready to be consumed, and

- made from or containing the following materials:

- expanded or extruded polystyrene foam,

- polyvinyl chloride,

- plastics with the additive “carbon black,” which is an additive used as a black colour pigment for plastic manufactured items that is produced through the partial or incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons, or

- oxo-degradable plastics, which are plastic materials that undergo accelerated fragmentation into smaller pieces when triggered by ultraviolet radiation or heat exposure in the presence of air;

SUP ring carriers, which are plastic manufactured items made entirely or in part from plastic and formed in the shape of a series of deformable rings or bands that are designed to surround beverage containers in order to carry them together;

SUP stir sticks, which are plastic manufactured items made entirely or in part from plastic and designed to stir or mix drinks, or to stop a drink from spilling out of a lid; and

SUP straws, which are plastic manufactured items made entirely or in part from plastic and formed in the shape of a drinking straw, including SUP flexible straws that have a corrugated section that allows the straw to bend and maintain its position at various angles.

The prohibitions in the Regulations will include performance criteria for checkout bags, cutlery and straws for the purposes of determining whether an item is single-use. There are no similar criteria for stir sticks, ring carriers, or foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, as all products meeting the definition in the Regulations are expected to be single-use.

Tests to determine whether a product meets the criteria for single-use must be conducted by a laboratory accredited under ISO/IEC 17025 entitled General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories, by an accrediting body that is a signatory to the International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation Mutual Recognition Arrangement. Alternatively, certification can be provided by a lab accredited under the Quebec Environmental Quality Act.

Prohibitions and exceptions

Prohibitions and exceptions for single-use plastic items except plastic straws

The Regulations will prohibit the manufacture, import, and sale (including for the purpose of export) of the categories of SUPs described in the previous subsection (with the exception of straws, described in the subsection below).

Prohibitions and exceptions for plastic straws

The Regulations will prohibit the manufacture, import, and sale of SUP straws, including straws packaged with other items such as beverage containers, as well as SUP flexible straws in any commercial, industrial, or institutional setting, except for the following activities:

- the manufacture and import of flexible plastic straws, where a “flexible” plastic straw has a corrugated section that allows the straw to bend and maintain its position at various angles;

- the sale of flexible plastic straws from one business to another, as well as sale to or in hospitals, medical facilities, long-term care facilities, and other care institutions, including the offering or provision of SUP flexible straws to patients or residents of any of these institutions; and

- the sale of packages of 20 or more flexible plastic straws in retail stores, on the condition that the straws are not kept on public display (though businesses may advertise that straws are available for purchase) and are provided only if requested by the customer (who can be any individual).

Coming into force

For SUP checkout bags, SUP cutlery, SUP foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, SUP stir sticks, and SUP straws, the prohibitions on manufacture and import will come into force six months after the Regulations are registered. The prohibition on sale of these items will come into force 18 months after the Regulations are registered. SUP flexible straws will not be subject to the prohibition on manufacture and import as there is a need to ensure supply of these items for people who need them, but their sale will be subject to special rules that will come into force 18 months after registration. The prohibitions on the manufacture and import of SUP ring carriers will come into force 12 months after the Regulations are registered. The prohibition on sale for SUP ring carriers, as well as the repeal of an exemption on the sale of SUP flexible straws packaged together with beverage containers, will come into force 24 months after the Regulations are registered. The Regulations repeal the exemption the manufacture, import and sale for the purposes of export for all categories of SUPs 42 months after the Regulations are registered.

Record keeping

Any person that manufactures or imports any of the six categories of SUPs for export for the 42-month period in which export is not prohibited must keep records providing written evidence that the SUP has been or will be exported. Records and supporting documents must be kept for at least five years after they are made.

Consequential amendments to other regulations under CEPA

Consequential amendments are needed to the Regulations Designating Regulatory Provisions for Purposes of Enforcement (Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999) (the Designation Regulations), which designate various provisions made pursuant to CEPA as being subject to the fine regime under the Environmental Enforcement Act. Specifically, any regulatory provisions listed in the Schedule to the Designation Regulations are subject to a minimum fine and higher maximum fines, should there be a successful prosecution of an offence involving harm or risk of harm to the environment, or obstruction of authority.footnote 30 Amendments are needed to include the Regulations in the Schedule to the Designation Regulations.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Pre-consultation activities

On October 7, 2020, the Department published the Discussion Paper on the CEPA Registryfootnote 2 outlining its proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution. The Discussion Paper was open to a 60-day public comment period from October 7 to December 9, 2020. During that period, the Department received written submissions representing the views of 245 stakeholder groups (151 industry members, 39 provincial, territorial, or municipal governments, two Indigenous groups, 32 NGOs, and 21 others). In addition, the Department received over 24 000 emails from individual Canadians and an online petition started by a civil society group that received over 100 000 signatures.

The Department also held five webinars and four online stakeholder discussion sessions between October 30 and November 27, 2020. Over 6 000 stakeholders were notified in advance of the webinars, which were also open to the public, and a total of 1 474 individuals participated. For the stakeholder discussion sessions, 100 to 150 stakeholders were invited to each session, with 35 to 50 participants attending each session. Three webinars and three stakeholder discussion sessions addressed the proposed prohibitions on certain SUPs. Topics for discussion included definitions, prohibitions, the potential need for exemptions, and the availability of substitute products. A description of each webinar and stakeholder discussion session, including topics discussed, stakeholder participation, and input received, is available in the What we heard report.

Commenters included industry stakeholders, provincial, territorial, or municipal governments, Indigenous groups, NGOs, and others. Civil society organizations and local governments agreed that plastic pollution is harming the Canadian environment and that Canadians are shouldering the costs of plastic pollution. Many of these organizations were supportive of a ban on the six SUPs targeted by the Regulations, and many also urged the Government of Canada to pursue more ambitious measures (e.g., ban additional SUPs). Provincial and territorial governments were also mostly supportive of the ban, although others expressed concern with potential economic impacts of a SUPs ban, among other things.

Comments covered a range of topics, but generally related to one of seven themes, namely: non-conventional plastics; accessibility concerns; Canada’s international trade commitments; unintended social, economic and environmental effects of substitute products; economic hardship due to the COVID-19 pandemic; the ban not being comprehensive enough; and the creation of national standards. A comprehensive summary of the comments received from these engagements is included in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on December 25, 2021.

Consultation following pre-publication in Canada Gazette, Part I

A 70-day public consultation period followed the publication of the proposed Regulations in Canada Gazette, Part I, on December 25, 2021. During this consultation period, stakeholders and members of the public were given an opportunity to provide the Department with written comments on the proposed Regulations. The Department received written submissions representing the views of 146 stakeholder groups (75 industry members, 22 provincial, territorial or municipal governments, one Indigenous group, 29 NGOs and 19 others). Table 3 presents the level of support of different stakeholder groups. As shown, the majority of stakeholders support the Regulations.

| Stakeholder type | Oppose | Partially support | Support | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous Organizations | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Industry | 41 | 24 | 10 | 75 |

| Local government | 0 | 4 | 17 | 21 |

| Miscellaneous | 3 | 8 | 8 | 19 |

| NGO | 0 | 6 | 23 | 29 |

| Provinces and territories | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Grand total | 44 | 42 | 60 | 146 |

The Department also received 25 notices of objection to the proposed Regulations and requests to establish a board of review to inquire into the nature and extent of the danger posed by one or more of the six categories of SUPs targeted by the proposed Regulations. The Minister has declined to form a board of review. All notices of objection, along with the Minister’s response letters, are available on the CEPA Registry.

In addition to written comments, the Government held online meetings with stakeholders to answer questions and receive feedback. As of March 11, 2022, a total of 48 online meetings with stakeholders took place, including with 27 businesses, 12 industry associations and their Members, four environmental non-governmental organizations, four municipal and provincial governments and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. In addition, the Department met with all provinces and territories via the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Many meetings involved multiple stakeholders and included representatives from Health Canada. During these meetings, stakeholders were given opportunities to pose questions and provide feedback. A survey was also sent to a large number of manufacturers across Canada seeking input on the impacts to this sector, with 12 responses received.

Oral and written feedback were considered in finalizing the Regulations. Comments covered a range of topics, but generally related to one of the eight following themes:

Coming into Force Dates

The proposed Regulations included a one-year coming into force period for the prohibitions on manufacture and import, plus an additional year for the prohibition on the sale of SUP checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware, ring carriers and stir sticks.

The Government received comments from NGOs and the public urging the Government to accelerate coming-into-force dates in recognition of the need for immediate action to prevent plastic pollution by restricting, or eliminating SUPs that pose a threat of harm to the environment.

In recognition of the actions of industry leaders and other jurisdictions, changing consumer preferences, as well as market trends that are moving away from SUPs, and the overarching goal of preventing plastic pollution, Departmental officials discussed with stakeholders the possibility of shortening the coming into force period. The Department heard from industry retailers and distributors that an accelerated implementation timeline could result in reduced or no access to substitutes once the prohibition on sale came into force. Some stakeholders cited supply chain issues during the COVID-19 pandemic as exacerbating this possibility. Industry manufacturers expressed concern that a shortened coming into force period would not provide sufficient time for re-tooling should they need to pivot their processes entirely.

The Government also heard from numerous stakeholders in the beverage industry that the coming into force period for ring carriers could not be shortened without incurring significant costs and disruptions. Stakeholders explained that shortened timelines would not be sufficient to select alternative packaging, purchase and receive new equipment, and re-arrange production facilities. The Government received similar feedback with regard to SUP flexible straws packaged together with beverage containers (e.g., attached to drink boxes).

This feedback was taken into consideration, as well as market trends and consumer preferences moving away from SUPs. As such, the prohibitions on manufacture and import will come into force six months after registration of the final Regulations and the prohibitions on sale will come into force 18 months after registration for single use plastic checkout bags, cutlery, straws, foodservice ware and stir sticks. For ring carriers, the prohibitions on manufacture and import will come into force 12 months after registration of the final regulations, and the prohibitions on sale for this item as well as for the repeal of a temporary exemption for the sale of SUP flexible straws packaged together with beverage containers will come into force 24 months after registration. A later coming into force date for sale will help avoid stranded inventory and allow sellers to deplete stockpiles and secure substitutes.

Exemption for Export

The proposed Regulations provided an indefinite exemption for the manufacture, import, and sale for the purposes of export of the targeted SUP items, so as to limit the economic impact on domestic manufacturers of these items. Following feedback from NGOs and the public that this exemption would be contrary to both the regulatory objective and to the Government of Canada’s broader zero plastic waste agenda, including commitments made by Canada under the to limit global plastic pollution, the Department raised the potential for removing this exemption during the 70-day consultation period.

The Department consulted broadly on removing the exemption for export, with a range of stakeholders including manufacturers, retailers and industry associations. In feedback from 29 virtual stakeholder meetings and in writing through official submissions on the Regulations regarding the phase-out of the exemption for export, a majority of industry stakeholders opposed removing the exemption for export, suggesting that this approach would result in lost jobs, stranded assets and facility closures. Some large manufacturers stated that a large proportion of their production is currently exported, and that an inability to sell to international markets would be economically harmful. It was also suggested by one stakeholder that removing the exemption for export would have little impact on global plastic pollution, as the market would be filled by foreign production. Some stakeholders suggested that these impacts could be mitigated by providing a transition period before removing the exemption. Industry suggestions for the specific length of time needed to transition varied but were generally three to five years, with consensus that the timeline to plan for and explore new markets, secure financing, order and install new equipment, hire and train new employees can take several years.

As a result of this feedback, the Department concluded that an appropriate balance between the environmental objectives of the Regulations and the time needed for industry stakeholders to transition would be to phase out the exemption for manufacture, import and sale for the purposes of export after 42 months. This timeline considers both industry’s proposition to allow for a transition period for the removal of the export exemption and the Government’s commitments to prevent plastic pollution around the world, including under the Ocean Plastics Charter.

Non-conventional Plasticsfootnote 31

The proposed Regulations did not differentiate between non-conventional (e.g., plant-based) plastics and conventional plastics made from petroleum-derived feedstock. Manufacturers of compostable plastics disagreed with this approach, stating that it would hinder innovation and growth in this sector, that compostable plastics bring environmental benefits and that they would incur economic losses. However, municipal and provincial governments, as well as recyclers and NGOs, were mostly supportive, stating that existing composting and recycling infrastructure is unable to process non-conventional plastics in a cost-effective manner. They urged the Government to also prohibit foodservice ware made from non-conventional plastics.

The Department recognizes the potential advantages of replacing single-use items made from conventional plastics with non-conventional plastic alternatives. Some of these benefits could include reducing fossil fuel consumption when plant-based materials replace carbon-intensive plastic source materials, and increasing food waste diversion in situations where contamination of plastics may present an obstacle to recycling. The Department also recognizes that these benefits must be weighed against current performance in compost facilities, where non-conventional plastics typically cannot be processed and are sent to landfills. In addition, while compostable plastics look very similar to the conventional plastics they replace, many are not designed to be recyclable. Mixing of compostable and conventional plastics can contaminate the recycling stream and reduce recycling recovery rates. The Science Assessment noted a lack of significant evidence that biodegradable, compostable, biobased, and oxo-degradable plastics will fully degrade in natural environments. Accordingly, the Regulations will treat single-use items made from non-conventional plastics in the same manner as their conventional plastic counterparts. The Department is working with partners and stakeholders, including provinces and territories, to develop the knowledge base about non-conventional plastics, which will inform future actions to promote innovation, clean growth and circularity in this sector for applications outside of the items prohibited by these Regulations.

SUP straws and accessibility

During the 70-day consultation period, stakeholders, particularly members of the public, raised the importance of ensuring continued access to SUP flexible straws for persons with disabilities or medical needs. The Department also received written comments from one disability advocacy group, one municipality and several individuals on the subject of straws and accessibility.

Feedback from industry stakeholders was mixed as to whether they would continue to produce or sell SUP flexible straws under the Regulations, given requirements to keep packages of straws out of sight of customers and only sell them on request, combined with an expected decline in Canadian market demand. Some major retailers and pharmacies indicated that they would continue to sell them, though the cost may increase due to reduced Canadian market demand. The City of Vancouver was engaged due to its bylaw requiring food vendors to provide SUP flexible straws upon request.

The Government of Canada is sensitive to the needs of Canadians, including Canadians with disabilities. The Department is committed to creating the conditions to keep SUP flexible straws available for anyone who needs them. The Regulations will allow Canadians with disabilities to continue to purchase SUP flexible straws for personal use, as well as to access them in hospitals and other medical or long-term care settings. These exemptions seek to balance the need to ensure accessibility options in Canada while protecting the environment from plastic pollution.

Canada’s International Trade Commitments

Some industry stakeholders gave their opinion that banning certain SUPs runs contrary to Canada’s interests in international trade, given the broad and growing trade network that provides Canadian companies with preferred access to diverse markets all over the world.